New Englanders support more offshore wind power – just don’t send it to New York

The regionalism that fuels the Red Sox-Yankees rivalry is also found in U.S. attitudes about energy production, a new study shows. That could have repercussions for the renewable energy transition.

In Rhode Island, home to the first offshore wind farm in the U.S., most people support expanding offshore wind power – with one important caveat.

Our research shows they’re less likely to support a wind power project if its energy flows to another state, and especially if it goes to a rival state. We found the same sentiment holds true on the New Hampshire coast.

Social scientists like us call this “regionalism,” and our research suggests it could have serious repercussions for the renewable energy transition.

Think about the rivalries and sometimes outright animosity among baseball fans. Few regional rivalries are as intense as the one between Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees fans. More than mere bluster, these place-based identities can strongly influence people’s thoughts and attitudes about rival cities in ways that extend far beyond the game. An allegiance to the Yankees can even influence perception of the distance between New York City and Boston.

But do regional identities affect attitudes toward energy development? Our studies of public attitudes toward offshore wind energy development indicate they might.

Which state gets the power matters

We conducted two surveys – one in Rhode Island and the other on the New Hampshire coast – to see how people felt about offshore wind power, including energy exports.

Overall, both groups supported wind power off their shores.

People were happiest if the power was produced for their home states. That wasn’t a surprise. Studies have showed that the public generally objects to energy exports, perhaps fueled by concerns over distributive justice. Distributive justice refers to discrepancies between who bears costs, like having power plants and equipment in sight, and who benefits, such as from revenue and energy produced.

The answers got more interesting when we asked about exporting power to specific states.

For people in New Hampshire, wind power projects that send power to their North Woods brethren in Maine were more palatable than projects that would connect to more urban Massachusetts.

For Rhode Islanders, a wind power project serving Massachusetts was OK, but not one serving New York. That reaction was consistent with the Red Sox-Yankees rivalry, with people in Red Sox-loving Rhode Island preferring the electricity be sent to New England instead.

Our study demonstrates that not only are people less supportive of other states’ claiming electricity produced off their shores, but it also matters which state is involved. It’s important to remember that once electricity goes into the Northeast grid, power from those wind turbines could go anywhere. The power company and state that contract with a wind farm can benefit from the price and credit for contributing that clean energy, but electricity itself isn’t limited to that state, and the climate and clean energy benefits are also more global. However, perceptions of who benefits matter for public acceptance of projects.

What this means for the future

How will this regionalism play out for actual projects? We are not sure, but these are not just hypothetical situations.

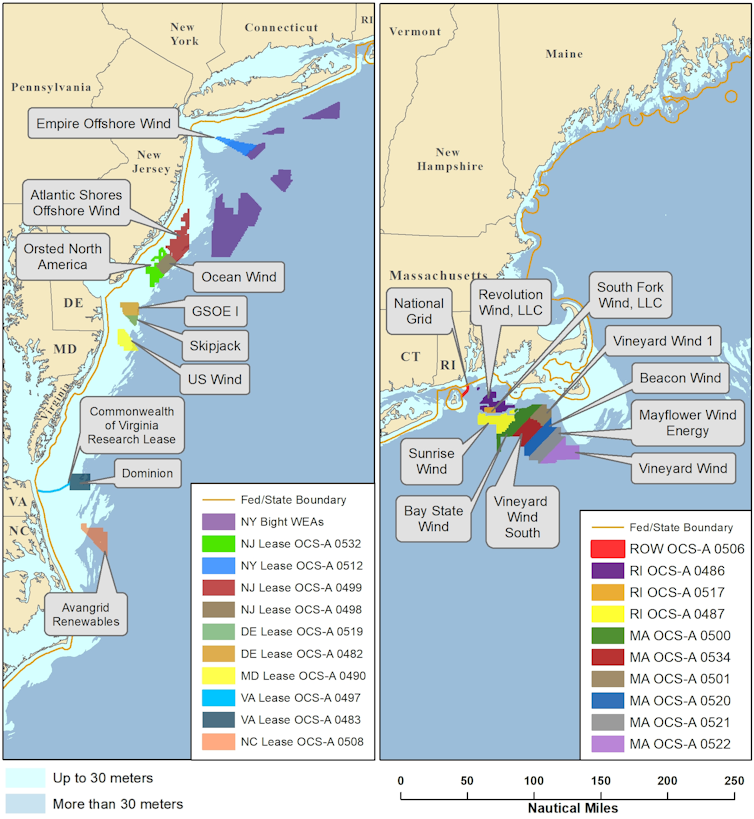

A project off the Delaware coast will supply power to Maryland. A project recently approved for development off Rhode Island will provide electricity to Long Island, New York.

The U.S. is poised for a rapid rise in offshore wind power. The Biden administration has committed enthusiastically to offshore wind development, and coastal states have already committed to generating nearly 45 gigawatts of offshore wind power. That’s close to the global total of around 57 gigawatts, and about 1,000 times the current U.S. production from its seven existing offshore wind turbines. The first large-scale project, Vineyard Wind, is under construction south of Martha’s Vineyard to ultimately provide up to 800 megawatts of electricity to its home state of Massachusetts.

Offshore wind energy has faced some controversy in the U.S. An early proposed project, Cape Wind, was scuttled by two decades of litigation. Public objections often arise over potential impacts to ocean views, the fishing industry and whales and other wildlife. Concerns over distributive justice could also turn public opinion against future projects.

What to do about it

One means of addressing fairness for energy projects is by providing “community benefits” such as sharing revenues with communities affected by offshore energy projects. We believe offshore energy developers and policymakers should broaden engagement to neighboring states and communities and consider how the project might affect nearby communities.

The energy transition may also be expedited by acknowledging place-based identities and planning accordingly, downplaying rivalries. For example, the federal government could move away from naming areas of the ocean designated for offshore wind development after specific states.

[Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

David Bidwell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article.

Jeremy Firestone is a former (uncompensated) Director of First State Marine Wind (FSMW), which owns a land-based wind turbine adjacent to the University of Delaware's Lewes campus. UD is the controlling owner of FSMW, with SGRE, the turbine manufacturer, owning a minority interest. Wind turbine revenues are used for research, and here provided grant funding for the Rhode Island research. Firestone has never received industry support from SGRE or any other entity.

Michael Ferguson receives funding from New Hampshire Seagrant

Read These Next

How does Iran go about selecting a new supreme leader? And who is in the running?

Media reports have cast the son of slain Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as a top candidate for supreme leader.…

Persian Gulf desalination plants could become military targets in regional war

Key sources of drinking water have been targets in past conflicts. And Iranian strikes have already…

Billions of dollars, decades of progress spent eliminating devastating diseases may be lost with und

Public health campaigns had made significant strides toward eradicating diseases like elephantitis and…