A century after the Appalachian Trail was proposed, millions hike it every year seeking 'the breath

When forester Benton MacKaye proposed building an Appalachian Trail 100 years ago, he was really thinking about preserving a larger region as a haven from industrial life.

The Appalachian Trail, North America’s most famous hiking route, stretches over 2,189 mountainous miles (3,520 kilometers) from Georgia to Maine. In any given year, some 3 million people hike on it, including more than 3,000 “thru-hikers” who go the entire distance, either in one stretch or in segments over multiple years.

The AT, as it’s widely known, is a national icon on a par with conservation touchstones like the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone’s Old Faithful geyser and the Florida Everglades. It symbolizes opportunity – the chance to set out on a life-altering experience in the great outdoors, or at least a pleasant walk in the woods.

Benton MacKaye, the classically trained forester who proposed creating the AT in 1921, saw it as a space where visitors could escape the stresses and rigors of modern industrial life. He also believed it could be a foundation for sound land-use patterns, with each section managed and cared for by local volunteers. MacKaye was a highly original thinker who called for protecting land on a continent-spanning scale and thought about how land use patterns could influence work and social relationships.

My research focuses on how people work together to promote large landscape conservation and to protect connectivity – physically linking patches of habitat, on land or at sea, so that animals and plants can move between them. MacKaye’s conception of the AT represents an early example of such comprehensive approaches to conservation.

An escape from industrial life

One hundred years ago, MacKaye laid out his vision for the AT in an article for the Journal of the American Institute of Architects. At that time, progressive thinkers were conceptualizing and promoting the idea of regional planning at many different scales.

Had MacKaye focused solely on a physical trail, the editors probably would have rejected his manuscript. But MacKaye envisioned the AT as a connecting cord that would run through and define a natural and rural region. In his view, maintaining the undeveloped character of the land would only become more essential in the face of an encroaching East Coast metropolis. And because it lay in the eastern U.S., the trail would “serve as the breath of a real life for the toilers in the bee-hive cities along the Atlantic seaboard and beyond,” he wrote.

By 1925 MacKaye organized an Appalachian Trail Conference to build the footpath, which was completed in 1937. The first thru-hiker, a World War II veteran named Earl Shaffer, completed the full journey in 1948. Over the following decades, most of the practical work on the AT focused on tying together the thread of the trail itself – a challenging mission of acquiring access rights to myriad public and private lands.

Maintaining the landscape around the AT in perpetuity is a bigger challenge. And climate change is making that issue more urgent, for the AT isn’t just a footpath for humans. It also provides two ways for plants and animals to shift their ranges in a changing world.

First, the trail offers a chance for wildlife and plants to move northward to cooler habitats on a warming planet. Second, species can also move up mountains to avoid warmer temperatures – and any thru-hiker has the blisters to prove that the AT has plenty of mountains.

More than a footpath

Beginning with MacKaye, many people over the past century have aspired to frame the AT as a platform for conservation at a regional scale – that is, extending far beyond the narrow trail corridor, which averages about 1,000 feet (300 meters) wide, or less than a quarter of a mile. One impetus is to provide a natural experience for hikers. Who wants to go exploring through exurban sprawl? Protecting land around the trail also expands spaces for plants and animals.

One of the best-known examples of large landscape approaches is the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, often referred to as Y2Y (I am the current chair of the Y2Y Council). Since the mid-1990s, this venture has striven to conserve habitat and rural working lands across a region that stretches some 2,000 miles (3,220 kilometers) north from the Greater Yellowstone region in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho to Canada’s Yukon Territory.

As the Y2Y experience has shown, conserving large landscapes around the AT will not be easy or straightforward – but it is possible. MacKaye worried about urban and suburban encroachment – a threat that has only grown more severe over the past hundred years. “Pinch points” include the mid-Atlantic portion of the AT, but development threats are present all along the trail.

Conservation advocates have identified key spots along the AT where land around the trail could be protected from development to support wildlife by preserving it as open space. They include highlands in northern New Jersey and southern New York; forests and wetlands in Vermont and New Hampshire; and Maine’s North Woods.

Land trusts and conservation organizations from Georgia to Maine are working to protect wild lands along the length of the AT and increasingly are coordinating their efforts through the Appalachian Trail Landscape Partnership. This initiative includes more than 100 partners, led by the Appalachian Trail Conservancy and the U.S. National Park Service, which has managed the AT since the passage of the 1968 National Scenic Trails Act.

Footpath and barrier

Benton MacKaye hoped that the AT would be a symbolic and literal pathway toward solving social problems. His initial vision for the trail included community camps, covering up to 100 acres, that would grow out of trail shelters into small settlements where people could live year-round and pursue “nonindustrial” activities such as study and recuperation. Eventually, he envisioned more permanent camps that would offer the opportunity to move from cities back to the country and work cooperatively on the land, raising food and harvesting timber.

“The camp community … is in essence a retreat from profit. Cooperation replaces antagonism, trust replaces suspicion, emulation replaces competition,” MacKaye wrote.

MacKaye’s grand hopes may have been idealistic, but fulfilling the AT’s potential for large landscape conservation in some of the most populated regions of North America is still a worthy goal. As MacKaye presciently concluded in his 1921 article, “This trail could be made to be, in a very literal sense, a battle line against fire and flood – and even against disease.” A century later, I believe the time has come for MacKaye’s vision of the trail to flourish as a mutually supportive endeavor among people and nature in a changing world.

[Over 109,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Charles C. Chester is the U.S. chair of the Yellowstone to Yukon Council, which works to connect and protect habitat in the Yellowstone to Yukon region of the western U.S. and Canada.

Read These Next

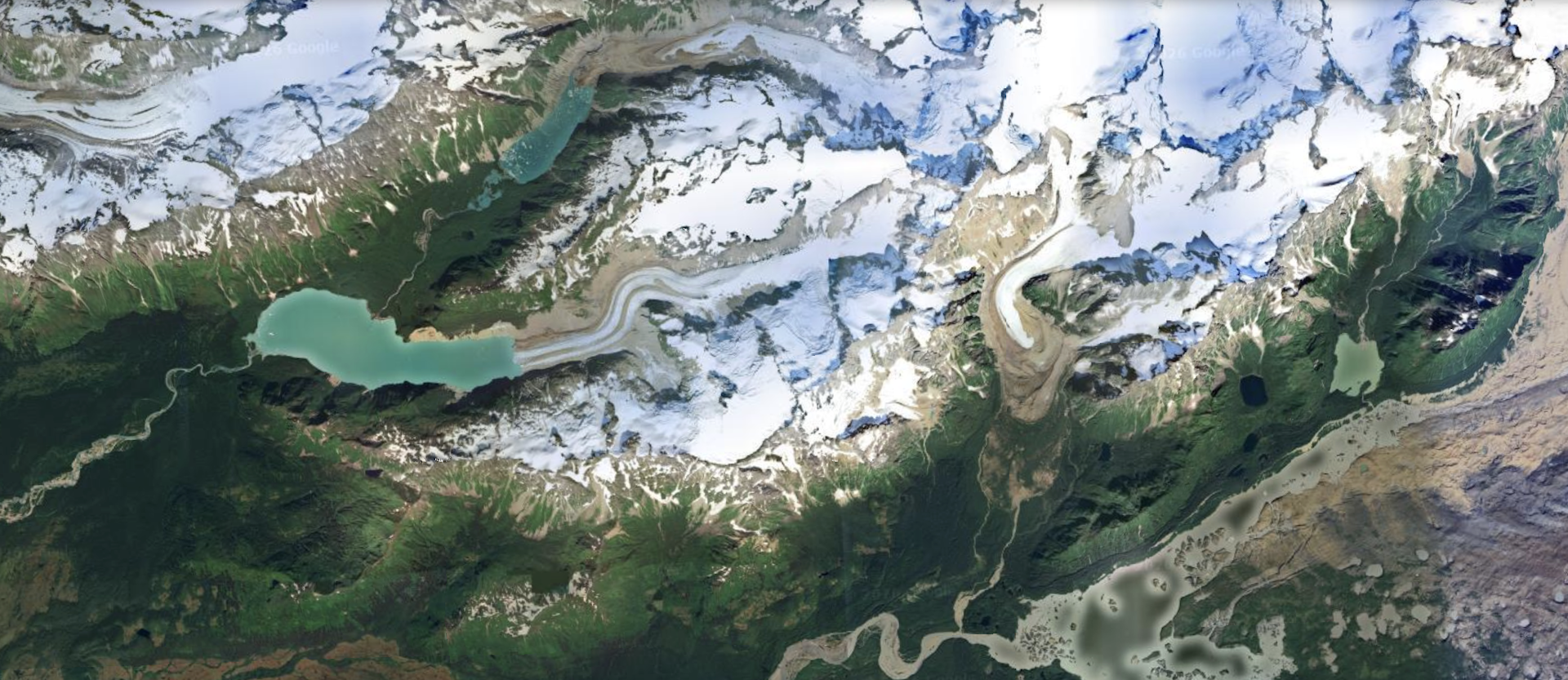

Alaska’s glacial lakes are expanding, increasing the risk of destructive outburst floods

Scientists mapped the evolution of 140 glacial lakes in Alaska and found a way to tell how much larger…

US is less prone to oil price shocks than in past decades

Oil prices affect the US economy differently than in past decades. Nowadays, the US is less reliant…

Abandoned Pennsylvania mines and waste-heat recycling could make the state’s massive new data center

In Pennsylvania, new data centers could require enough electricity to power 11 million homes.