The US Army tried portable nuclear power at remote bases 60 years ago – it didn't go well

Nearly 60 years after a radiation-leaking reactor was removed from a US Army base on the Greenland ice sheet, the military is exploring portable nuclear reactors again.

In a tunnel 40 feet beneath the surface of the Greenland ice sheet, a Geiger counter screamed. It was 1964, the height of the Cold War. U.S. soldiers in the tunnel, 800 miles from the North Pole, were dismantling the Army’s first portable nuclear reactor.

Commanding Officer Joseph Franklin grabbed the radiation detector, ordered his men out and did a quick survey before retreating from the reactor.

He had spent about two minutes exposed to a radiation field he estimated at 2,000 rads per hour, enough to make a person ill. When he came home from Greenland, the Army sent Franklin to the Bethesda Naval Hospital. There, he set off a whole body radiation counter designed to assess victims of nuclear accidents. Franklin was radioactive.

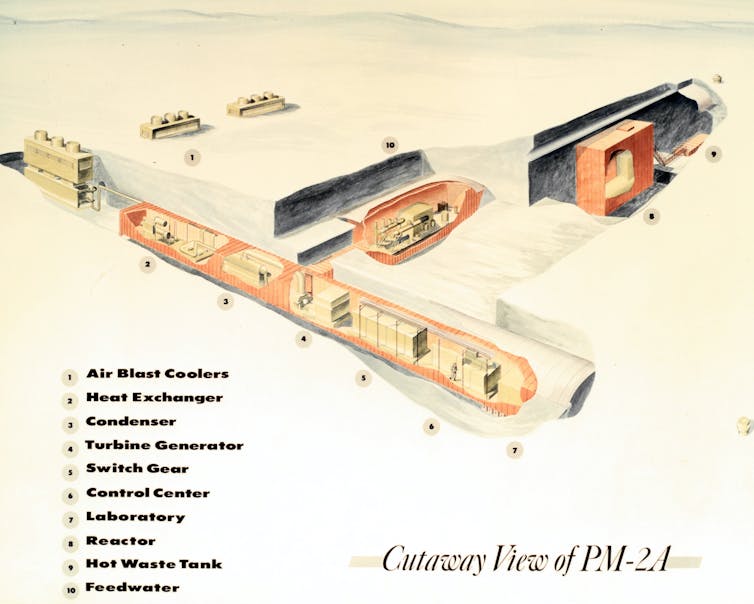

The Army called the reactor portable, even at 330 tons, because it was built from pieces that each fit in a C-130 cargo plane. It was powering Camp Century, one of the military’s most unusual bases.

Camp Century was a series of tunnels built into the Greenland ice sheet and used for both military research and scientific projects. The military boasted that the nuclear reactor there, known as the PM-2A, needed just 44 pounds of uranium to replace a million or more gallons of diesel fuel. Heat from the reactor ran lights and equipment and allowed the 200 or so men at the camp as many hot showers as they wanted in that brutally cold environment.

The PM-2A was the third child in a family of eight Army reactors, several of them experiments in portable nuclear power.

A few were misfits. PM-3A, nicknamed Nukey Poo, was installed at the Navy base at Antarctica’s McMurdo Sound. It made a nuclear mess in the Antarctic, with 438 malfunctions in 10 years including a cracked and leaking containment vessel. SL-1, a stationary low-power nuclear reactor in Idaho, blew up during refueling, killing three men. SM-1 still sits 12 miles from the White House at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. It cost US$2 million to build and is expected to cost $68 million to clean up. The only truly mobile reactor, the ML-1, never really worked.

Nearly 60 years after the PM-2A was installed and the ML-1 project abandoned, the U.S. military is exploring portable land-based nuclear reactors again.

In May 2021, the Pentagon requested $60 million for Project Pele. Its goal: Design and build, within five years, a small, truck-mounted portable nuclear reactor that could be flown to remote locations and war zones. It would be able to be powered up and down for transport within a few days.

The Navy has a long and mostly successful history of mobile nuclear power. The first two nuclear submarines, the Nautilus and the Skate, visited the North Pole in 1958, just before Camp Century was built. Two other nuclear submarines sank in the 1960s – their reactors sit quietly on the Atlantic Ocean floor along with two plutonium-containing nuclear torpedos. Portable reactors on land pose different challenges – any problems are not under thousands of feet of ocean water.

Those in favor of mobile nuclear power for the battlefield claim it will provide nearly unlimited, low-carbon energy without the need for vulnerable supply convoys. Others argue that the costs and risks outweigh the benefits. There are also concerns about nuclear proliferation if mobile reactors are able to avoid international inspection.

A leaking reactor on the Greenland ice sheet

The PM-2A was built in 18 months. It arrived at Thule Air Force Base in Greenland in July 1960 and was dragged 138 miles across the ice sheet in pieces and then assembled at Camp Century.

When the reactor went critical for the first time in October, the engineers turned it off immediately because the PM-2A leaked neutrons, which can harm people. The Army fashioned lead shields and built walls of 55-gallon drums filled with ice and sawdust trying to protect the operators from radiation.

The PM-2A ran for two years, making fossil fuel-free power and heat and far more neutrons than was safe.

Those stray neutrons caused trouble. Steel pipes and the reactor vessel grew increasingly radioactive over time, as did traces of sodium in the snow. Cooling water leaking from the reactor contained dozens of radioactive isotopes potentially exposing personnel to radiation and leaving a legacy in the ice.

When the reactor was dismantled for shipping, its metal pipes shed radioactive dust. Bulldozed snow that was once bathed in neutrons from the reactor released radioactive flakes of ice.

Franklin must have ingested some of the radioactive isotopes that the leaking neutrons made. In 2002, he had a cancerous prostate and kidney removed. By 2015, the cancer spread to his lungs and bones. He died of kidney cancer on March 8, 2017, as a retired, revered and decorated major general.

Camp Century’s radioactive legacy

Camp Century was shut down in 1967. During its eight-year life, scientists had used the base to drill down through the ice sheet and extract an ice core that my colleagues and I are still using today to reveal secrets of the ice sheet’s ancient past. Camp Century, its ice core and climate change are the focus of a book I am now writing.

The PM-2A was found to be highly radioactive and was buried in an Idaho nuclear waste dump. Army “hot waste” dumping records indicate it left radioactive cooling water buried in a sump in the Greenland ice sheet.

When scientists studying Camp Century in 2016 suggested that the warming climate now melting Greenland’s ice could expose the camp and its waste, including lead, fuel oil, PCBs and possibly radiation, by 2100, relations between the U.S, Denmark and Greenland grew tense. Who would be responsible for the cleanup and any environmental damage?

Portable nuclear reactors today

There are major differences between nuclear power production in the 1960s and today.

The Pele reactor’s fuel will be sealed in pellets the size of poppy seeds, and it will be air-cooled so there’s no radioactive coolant to dispose of.

Being able to produce energy with fewer greenhouse emissions is a positive in a warming world. The U.S. military’s liquid fuel use is close to all of Portugal’s or Peru’s. Not having to supply remote bases with as much fuel can also help protect lives in dangerous locations.

But, the U.S. still has no coherent national strategy for nuclear waste disposal, and critics are asking what happens if Pele falls into enemy hands. Researchers at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the National Academy of Sciences have previously questioned the risks of nuclear reactors being attacked by terrorists. As proposals for portable reactors undergo review over the coming months, these and other concerns will be drawing attention.

The U.S. military’s first attempts at land-based portable nuclear reactors didn’t work out well in terms of environmental contamination, cost, human health and international relations. That history is worth remembering as the military considers new mobile reactors.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Paul Bierman receives funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and

Tiny particles bounce light around in a unique way, a property that researchers are using to detect…

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…