This supermoon has a twist – expect flooding, but a lunar cycle is masking effects of sea level rise

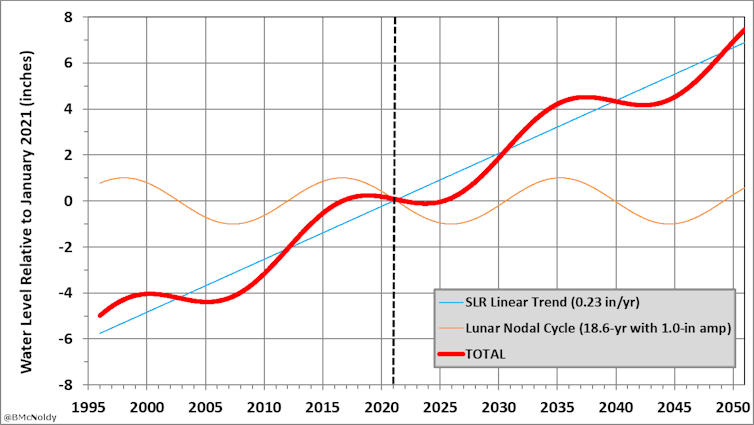

That doesn't mean sea level rise has stopped – it hasn't. When that lunar cycle starts upward again, it will mean double trouble for places like Miami.

A “super full moon” is coming on April 27, 2021, and coastal cities like Miami know that means one thing: a heightened risk of tidal flooding.

Exceptionally high tides are common when the moon is closest to the Earth, known as perigee, and when it’s either full or new. In the case of what’s informally known as a super full moon, it’s both full and at perigee.

But something else is going on with the way the moon orbits the Earth that people should be aware of. It’s called the lunar nodal cycle, and it’s presently hiding a looming risk that can’t be ignored.

Right now, we’re in the phase of an 18.6-year lunar cycle that lessens the moon’s influence on the oceans. The result can make it seem like the coastal flooding risk has leveled off, and that can make sea level rise less obvious.

But communities shouldn’t get complacent. Global sea level is still rising with the warming planet, and that 18.6-year cycle will soon be working against us.

I am an atmospheric scientist who keeps a close eye on sea level rise in Miami. Here’s what you need to know.

What the moon has to do with coastal flooding

The moon’s gravitational pull is the dominant reason we have tides on Earth. More specifically, Earth rotating beneath the moon once per day and the moon orbiting around Earth once per month are the big reasons that the ocean is constantly sloshing around.

In the simplest terms, the moon’s gravitational pull creates a bulge in the ocean water that is closest to it. There’s a similar bulge on the opposite side of the planet due to inertia of the water. As Earth rotates through these bulges, high tides appear in each coastal area every 12 hours and 25 minutes. Some tides are higher than others, depending on geography.

The sun plays a role too: Earth’s rotation, as well as its elliptic orbit around the sun, generates tides that vary throughout the day and the year. But that impact is less than half of what the moon contributes.

This gravitational tug-of-war on our water was discovered nearly 450 years ago, though it’s been happening for nearly four billion years. In short, the moon has very strong control over how we experience sea level. It doesn’t affect sea level rise, but it can hide or exaggerate it.

So, what is the lunar nodal cycle?

To begin, we need to think about orbits.

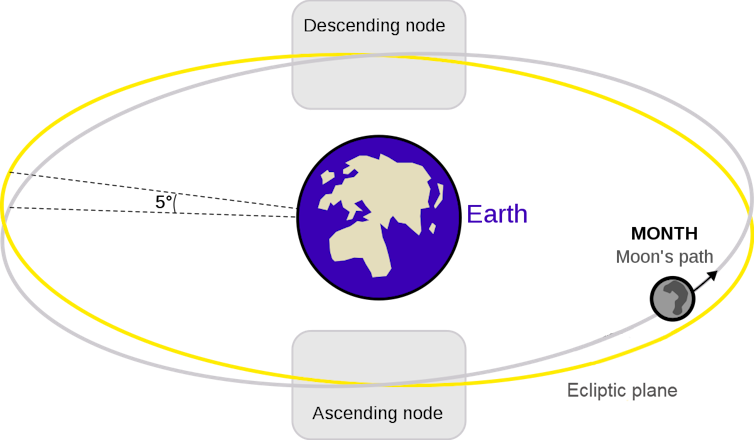

Earth orbits the sun in a certain plane – it’s called the ecliptic plane. Let’s imagine that plane being level for simplicity. Now picture the moon orbiting Earth. That orbit also lies on a plane, but it’s slightly tilted, about 5 degrees relative to the ecliptic plane.

That means that the moon’s orbital plane intersects Earth’s orbital plane at two points, called nodes.

The Moon’s orbital plane precesses, or wobbles, to a maximum and minimum of +/- 5 degrees over a period of about 18.6 years. This natural cycle of orbits is called the Lunar Nodal Cycle. When the lunar plane is more closely aligned with the plane of Earth’s equator, tides on Earth are exaggerated. Conversely, when the lunar plane tilts further away from the equatorial plane, tides on Earth are muted, relatively.

The lunar nodal cycle was first formally documented in 1728 but has been known to keen astronomical observers for thousands of years.

What effect does that have on sea level?

The effect of the nodal cycle is gradual – it’s not anything that people would notice unless they pay ridiculously close attention to the precise movement of the moon and the tides for decades.

But when it comes to predictions of tides, dozens of astronomical factors are accounted for, including the lunar nodal cycle.

It’s worth being aware of this influence, and even taking advantage of it. During the most rapid downward phase of the lunar nodal cycle – like we’re in right now – we have a bit of a reprieve in the observed rate of sea level rise, all other things being equal.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

These are the years to implement infrastructure plans to protect coastal areas against sea level rise.

Once we reach the bottom of the cycle around 2025 and start the upward phase, the lunar nodal cycle begins to contribute more and more to the perceived rate of sea level rise. During those years, the rate of sea level rise is effectively doubled in places like Miami. The impact varies from place to place since the rate of sea level rise and the details of the lunar nodal cycle’s contribution vary.

Another “super full moon” will be coming up on May 26, so like the one in April, it’s a perigean full moon. Even with the lunar nodal cycle in its current phase, cities like Miami should expect some coastal flooding.

This story is part of Oceans 21

Our series on the global ocean opened with five in depth profiles. Look out for new articles on the state of our oceans in the lead up to the UN’s next climate conference, COP26. The series is brought to you by The Conversation’s international network.

Brian McNoldy serves as a volunteer science advisor for Coastal Risk Consulting.

Read These Next

Honoring Colorado’s Black History requires taking the time to tell stories that make us think twice

This year marks the 150th birthday of Colorado and is a chance to examine the state’s history.

50 years ago, the Supreme Court broke campaign finance regulation

A gobsmacking amount of money is spent on federal elections in the US. The credit or blame for that…

When civil rights protesters are killed, some deaths – generally those of white people – resonate mo

From the civil rights era of the 1960s until today, white victims of government violence have received…