Opportunities to practice real-life philanthropy bring academic benefits

At Northern Kentucky University, students award grants to nonprofits in need. A study found that the program is paying off in other ways as well.

A crisis shelter for battered women. A nonprofit that provides wigs and makeup for breast cancer patients. An organization that helps parents of children addicted to heroin.

All three of these groups have benefited from US$2,000 grants made by college students who participate in an unusual hands-on philanthropy program. The program – which embeds aspects of philanthropy into existing classes ranging from costume design to communications – provides practical experience on how to identify nonprofits worth supporting.

The program is formally known as the Mayerson Student Philanthropy Project. We both have a hand in directing it at our university. It began in the fall of 2000 at Northern Kentucky University. Since then, students have given close to $1 million to a wide array of nearly 400 nonprofits, such as animal shelters, food pantries, children’s homes and drug rehab centers.

Higher graduation rates

But the long list of recipients is only part of the story. The other part is captured in a 2020 study that we published in the Journal of College Student Retention, along with co-authors Megan Downing and Joseph Nolan. We found that participants had a “substantially higher four-year graduation rate in comparison to students overall.”

Specifically, students in our sample who took this class when they were sophomores went on to graduate at a rate of 58%, versus 24% overall.

They are also less likely to drop the class. Specifically, students who took a class with a philanthropy component withdrew at a rate of 6.0%, versus 10.3% for Northern Kentucky University students overall.

The study compared a sample of 570 students who have taken a Mayerson class between 2014 and 2017 to Northern Kentucky University students as a whole during the same time.

Fostering engagement

What about the program makes students more likely to stick with the class and college overall?

If you ask students, they say the program fosters a sense of being connected to the community and raises awareness about people in need who live nearby.

“I have always been interested in helping the community, but I was never connected enough to know what is out there,” one student said in a response to a survey. “This provided a real eye opener, I now understand more about my community and have plans to be involved.”

Professors at Northern Kentucky University who are familiar with the program talk about the engaging nature of hands-on philanthropy. They say it can transform how students see their ability to make a difference.

Goals of giving

Named for the Manuel D. and Rhoda Mayerson Foundation, the Cincinnati-based foundation that provided the startup funding, the program began in the fall of 2000 with only a few classes each semester. It now has about 15 classes a semester. Typically, each class awards $2,000 at the end of the course.

The program is the brainchild of former Northern Kentucky University president James Votruba and Neal Mayerson – a psychotherapist, businessman and philanthropist.

They designed the program as a way to teach students how to invest in solutions to address community needs. Data shows the program has accomplished that goal. More than 82% of the students surveyed at the end of their Mayerson class say the philanthropy component had a positive impact on their sense of personal responsibility to their community. They also became more familiar with the nonprofits operating near their campus and of their local community’s needs.

Proven benefits

Other studies have found that hands-on philanthropy instruction is worthwhile.

A 2017 study, for example, found that students who take these classes are significantly more likely than their classmates to be aware of social problems and nonprofits in their community.

A 2012 study found that graduates who took these classes were more likely to volunteer, serve on nonprofit boards and give to charity.

The money our Northern Kentucky University students give away comes primarily from donors – including both foundations and individuals – in and around Cincinnati, although one major donor is from outside our region.

Class design

An important feature of the program is that – instead of being based on standalone “philanthropy classes” – it embeds a philanthropic component into existing classes in different fields and subjects. The philanthropy takes on different forms in different classes.

For instance, Professor Ronnie Chamberlain has her costume design students make doll-sized garments as they polish their design skills for the stage.

When she started teaching the costume design class, she used to have the dolls put into storage and would let students take the costumes home. But back in 2014, she redesigned the class to include a hands-on philanthropy component. She had the students visit nearby nonprofits, schools, children’s homes, community centers and social service agencies. At the end of the semester, the students would pick an agency to receive the costumed dolls.

Chamberlain recalls a student having trouble with a zipper and wondering if her imperfect effort was good enough. “Would it be OK if it were a gift under your Christmas tree?” Chamberlain asked. The student worked on the zipper until she got it right.

“I usually get that question two or three times a semester,” Chamberlain said. “After I added the philanthropy component to my class, I get it once and that’s it.”

In a typical Mayerson project class, students award a small grant of $2,000 to the nonprofit they select. Chamberlain used half her funds to buy dolls. The nonprofit receiving the dolls got a check for $1,000 to buy other toys, since not all children might want a doll.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

Fulfilling needs

In a communication class called “Strategies of Persuasion,” representatives from various nonprofits visit to make a pitch for a grant. After students evaluate the pitch, they raise money from friends and family using persuasive letters. The money is matched by donors. Finally, students who favor one nonprofit must persuade their classmates to vote on which one should get the grant.

In this class, students start with $1,000 from one of the program’s donors and must raise at least an equal amount so that the class has $2,000 to invest by the end of the semester.

Students say they appreciate learning more about the different needs that exist in the community.

“I really enjoyed the process of looking at all the nonprofits, there are so many, and so many people need help,” one student wrote in response to a survey.

“You always know there is need, but this project made me feel like I was helping in some way, even if it was indirectly, and I liked the feeling. I want to do more of it in the future.”

Kajsa Larson does not personally receive any money from this program. But I am the faculty coordinator to the Mayerson Student Philanthropy Project at Northern Kentucky University.

Mark A. Neikirk does not personally receive any money from this program. But I am the paid executive director of the Scripps Howard Center for Civic Engagement at Northern Kentucky University, which operates this program.

Read These Next

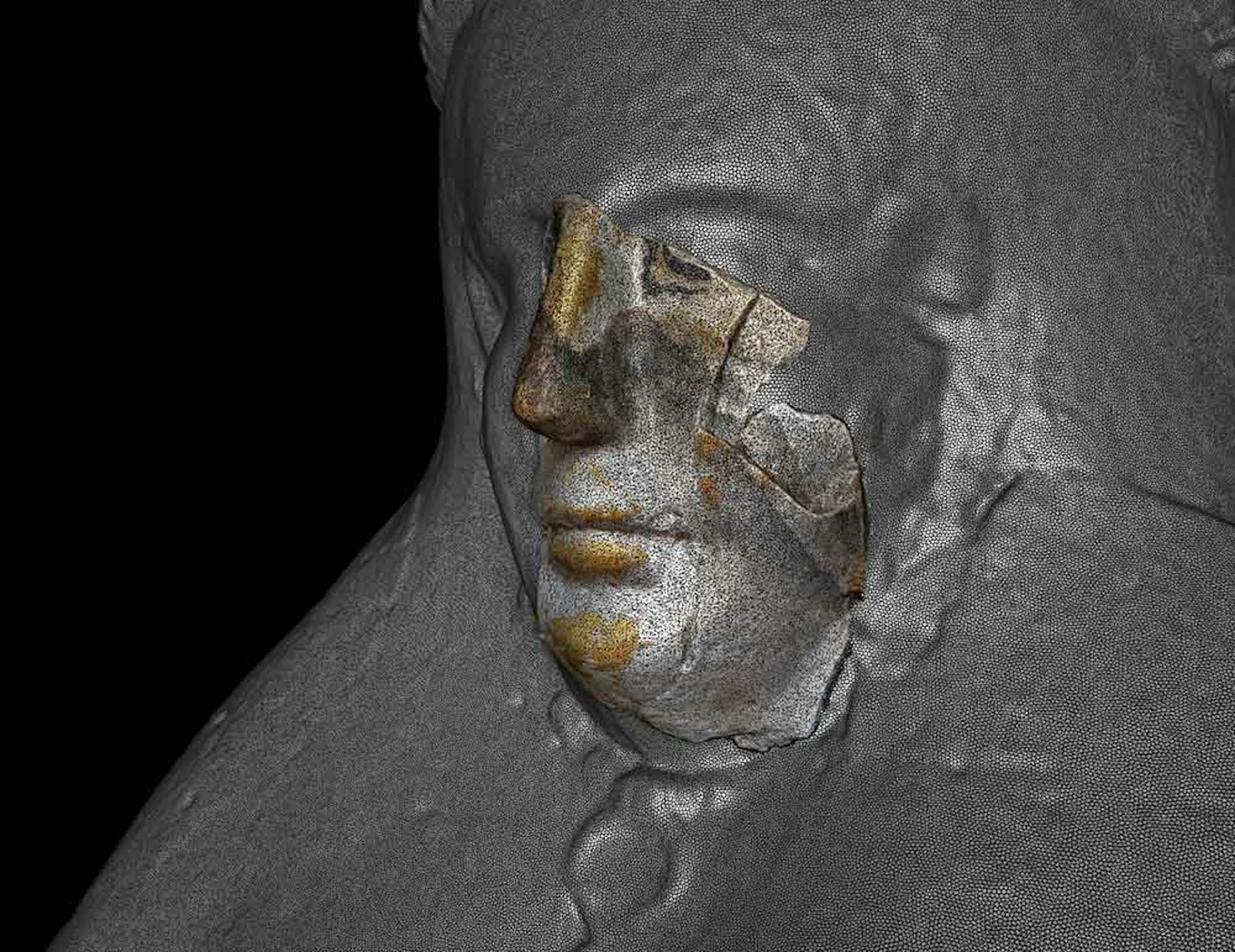

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…

The intensity and perfectionism that drive Olympic athletes also put them at high risk for eating di

Athletes in sports where weight and body image come into play, such as figure skating and wrestling,…

Are women board members risk averse or agents of innovation? It’s complicated, new research shows

The effect of women board members on patent activity hinges on whether the company is meeting performance…