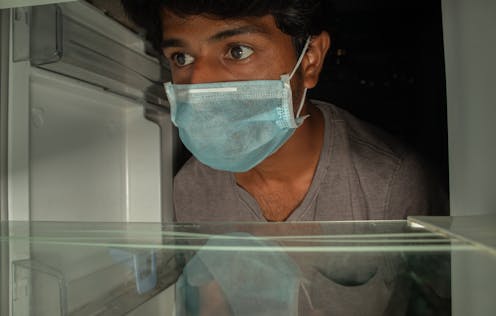

Pandemic threatens food security for many college students

Concerns about having enough to eat are worsening among college students during the pandemic. This could ultimately affect how many finish school, two scholars argue.

When university presidents were surveyed in spring of 2020 about what they felt were the most pressing concerns of COVID-19, college students going hungry didn’t rank very high.

Just 14% of the presidents listed food or housing insecurity among their top five concerns.

Granted, these academic leaders had plenty of other things to worry about. Some 86% said they were worried about fall enrollment – a concern that has shown itself to be a legitimate one, especially in light of the fact that low-income students have been dropping out of college at what one headline described as “alarming rates.”

As researchers who specialize in the study of food insecurity, we see the dropout rate as being related to a host of underlying issues. And not having enough to eat is one of them.

Data support this view. The signs of this growing problem - known as food insecurity – began to emerge when the COVID-19 epidemic was beginning to take its toll.

One spring 2020 report found that 38% of students at four-year universities were food-insecure in the previous 30 days. That was up 5 percentage points from 33% in the fall of 2019.

College students, clearly, warrant special attention as a group. These rates of food insecurity are more than three times the rate of that in all U.S. households, which was estimated to be 10.5% in 2019.

Historically, estimates of food insecurity among college students have ranged from 10% to 75%, according to 50 studies from U.S. academic institutions carried out from 2009 to before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Why it matters

This is not just a matter of growling stomachs. This is a straight-up education and health issue.

When students don’t really know if they’ll be able to get enough to eat, it can lead to a series of problems that make it harder to stay in school. For instance, it can affect academic performance and sleep quality. It can also lead to poor mental and physical health outcomes for college students.

Food insecurity can also result in disrupted eating patterns if there is not enough food or the variety or quality of what someone eats is low.

Campus food pantries

Previous strategies by colleges and universities to fight hunger in their student bodies have varied widely. They include campus food pantries, emergency cash assistance and nutrition education through noncredit classes or workshopse.

These strategies were put to the test during the spring 2020 semester, when nearly three in five students said they had trouble meeting their own basic needs during the pandemic.

College food pantries saw big increases in demand. Others said they were getting less donated food. This made it even harder to meet the rising food needs of students.

Campus food pantries largely rely on local or regional food banks, which have been dealing with greater demand than they are able to meet during the pandemic.

The many students who are attending college remotely will, of course, have less access to campus resources like food pantries.

Federal help

Other potential ways to get more food are government programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, known as SNAP. Yet the majority of able-bodied students are not eligible. Long-standing restrictions, like the college SNAP rule, prevent full-time students from receiving these benefits.

Such regulatory hurdles were created under the assumption that most students can rely on their parents to get enough to eat. However, college students have vastly different levels of financial support. Some students can rely on their parents for everything and others cannot rely on their parents for anything.

Decreased reliance on parental financial support is especially common for first-generation students and students of color, who now make up 45% of enrolled college students.

Under normal circumstances, many college students might rely on part-time jobs to pay for their food.

Two-thirds of the students who were employed before the pandemic said that job insecurity was a problem for them, according to the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice #RealCollege survey. As the number of jobless young Americans remains elevated, unemployment and underemployment remain a problem.

Jobless students face a potential double threat of less money for food and unemployment benefits cutting off their access to SNAP because the program requires most students to work at least part time.

Attempts have been made at both the federal and state levels to meet the basic food needs of college students. Lawmakers have focused on temporarily suspending eligibility requirements or expanding the criteria for participating in nutrition assistance programs.

Seventeen bills aiming to address food insecurity among college students were introduced to Congress during the 2019-2020 legislative session. However, these proposals failed to gain momentum, and the four COVID-19 stimulus bills to date have not addressed the hunger needs of college students. Notably, some students were ineligible to personally receive a CARES Act stimulus relief payment because they were claimed as dependents by their parents.

Short-term solutions

Universities and colleges can make it a priority to ensure students are aware of all available campus resources and services. They can also potentially help students apply for federal assistance benefits.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Campus food pantries are not a fully effective and efficacious solution for the scale of college food insecurity, but they can be a good interim solution to increase access to food for students.

Campuses without food pantries can start one, making use of resources the College and University Food Bank Alliance provides. Schools with food pantries can try to get them to reach more students.

Universities and colleges can also lean on one another for support. The Alabama Campus Coalition for Basic Needs is a great example of this. It brings together 10 universities across the state of Alabama collectively working to address student food insecurity.

Matthew J. Landry receives funding support from the National Institutes of Health. He is currently a Science Policy Fellow for the American Society for Nutrition. These organizations had no role in this article.

Heather Eicher-Miller receives or has received funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Federal Office of Rural Health, the University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research, Eli Lilly and Company, and Purdue University. She has served as a consultant to Colletta Consulting, Mead Johnson, the National Dairy Council, the Indiana Dairy Association, and the American Egg Board. She has previously received travel support to present research findings from the Institute of Food Technologists and International Food Information Council. However, these organizations had no role in this article.

Read These Next

Last nuclear weapons limits expired – pushing world toward new arms race

The expiration of the New START treaty has the US and Russia poised to increase the number of their…

The greatest risk of AI in higher education isn’t cheating – it’s the erosion of learning itself

Automating knowledge production and teaching weakens the ecosystem of students and scholars that sustains…

Why Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’ endures

The artist used daring imagery that sparked controversy from the moment it was unveiled.