What should replace Confederate statues?

As momentum builds to remove statutes that pay homage to Confederates and others who sought to uphold white supremacy, a historian explores questions about what should be erected in their place.

Ever since the University of South Carolina put up a statue of Richard T. Greener – who in 1873 became the school’s first Black professor – one of my favorite things to do has been to eat lunch on a bench nearby to watch how people interact with it.

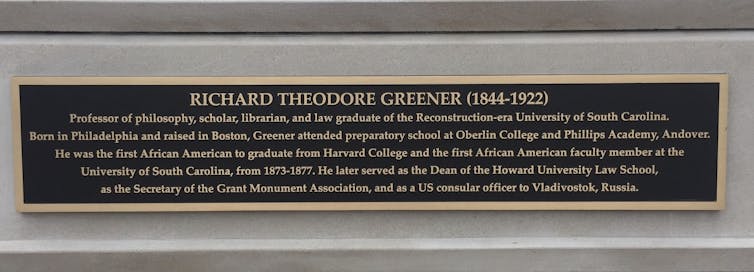

Greener – who taught for four years when the university was desegregated during Reconstruction – went on to become a widely recognized lawyer, scholar, diplomat and activist for racial justice.

Some people come to the statue with a purpose, often to show it to others and take pictures. Others pass by and look at Greener’s likeness with curiosity. Usually when they read the plaque at the base, they pause with a look of surprise. I watch them read the plaque again and then walk around the statue as if to evaluate if this story could be true.

As a historian who examines the role that race played in the social and political structure of the South, especially as it relates to higher education, I know that not only is the story completely accurate, but I believe how the statue in honor of Greener came to be holds important lessons for today. This is a time when there is an intensified movement – particularly at America’s colleges and universities – to remove statues and names from buildings or organizations that pay homage to Confederate leaders and others with racist views.

As part of America’s reckoning with its oppressive past, the nation now faces the question not just of what statues and other images should be taken down, but what else – if anything – should be put up in their place. What should become of the empty pedestals where some of these statues once stood? Should they remain empty or be replaced with memorials that honor the victims of – and victors over – racism?

I believe the story of the Greener statue helps illuminate a way forward.

Harvard’s first Black graduate

The story begins in the fall of 2010, when Katherine Chaddock, a professor of higher education, mentioned during a graduate course she was teaching that she had seen a plaque near Harvard Square commemorating Greener as Harvard’s first Black graduate. A student then asked why he hadn’t heard of Greener and what there was on campus to commemorate and remember him.

A play about Greener’s life – and named for one of his essays, “The White Problem,” in which he took on the ideology of white supremecy – was commissioned and performed as part of the University of South Carolina’s bicentennial in 2001. But that play has not been performed since. There is a scholarship in memory of Greener given by the Black Alumni Council, and a portrait of Greener hangs in the president’s office, but these have a limited audience.

Chaddock started a dialogue with her graduate students and others from the Higher Education and Student Affairs program, along with me and Lydia Mattice Brandt, an art history professor.

Students, faculty, staff, alumni and community members all got involved. We ultimately decided that a statue was the best way to publicly honor Greener. That statue was unveiled on February 21, 2018.

During the unveiling ceremony, I pointed out how some people wanted to forget when the campus desegregated briefly during Reconstruction and hired its first Black professor.

For example, when white students returned to campus after it reopened as an all-white institution in 1880 – three years after its desegregated status from 1873 to 1877 came to an end – they ripped or blacked out pages from the ledgers of the debating societies that had been used by Black students during Reconstruction.

Who was Richard T. Greener?

Richard T. Greener was appointed professor of mental and moral philosophy at the University of South Carolina in 1873. As a student at Harvard (class of 1870), he won both the Boylston Prize for elocution and the Bowdoin Prize for writing.

At the time of his appointment, the South Carolina legislature was majority Black, a radical change brought about by the revision of the state constitution in 1868 allowing for universal suffrage, meaning that for the first time all men, including Black men, in the state could vote.

In addition to teaching philosophy, Latin and Greek, Greener served as university librarian and reorganized and modernized the library’s catalog. He also recruited Black students throughout the state and developed a preparatory program to help them succeed. While on faculty, he earned a law degree. His diploma and law license were found in Chicago in 2012 and later obtained by the University of South Carolina.

After being forced out of South Carolina because the university was closed, Greener served as dean of the Howard University School of Law, as a U.S. diplomat in Vladivostok, Russia and as the chief administrator of the Grant Memorial Association. He also practiced law. His debates with Frederick Douglass about Black migration helped Douglass better understand the nature of the South. W.E.B. DuBois considered him part of the “talented tenth,” whom DuBois regarded as the leaders among African Americans.

Greener died in 1922 in Chicago, where he had gone to live with family and practice law after leaving Russia.

As Chaddock explains in her biography, “Uncompromising Activist: Richard Greener, First Black Graduate of Harvard College,” he was a complex man living in a complex time. Even though he lived only four years in the state, he always considered himself a South Carolinian, Rep. James Clyburn emphasized in his keynote address at the unveiling ceremony.

Why do we need new memorials?

Historian Eric Foner has argued that Americans should erect new statues because “our public monuments have not kept up.” With Greener’s statue, the University of South Carolina showed that it would recognize, seek to understand and celebrate forgotten parts of its past.

Political science professor Todd Shaw connected Greener’s pioneering legacy to his own in his remarks before the statue was officially unveiled. Shaw in 2017 became the first African American to chair the University of South Carolina’s political science department. “In each case, for varying reasons, both Greener and I were and are proud to serve though the road to our appointments were admittedly a long time in coming.”

The statue not only celebrates Greener’s contributions, it stands as a symbol of how we can reclaim and understand a lost, misunderstood or misrepresented history.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Whom will your campus honor?

Making the statue a reality required a grassroots process that took more than seven years. The process involved identifying a site with the university architect, approvals from the Board of Trustees and fundraising. President Harris Pastides helped push it over the finish line and supported it as a means to help “build, not divide” the community.

The point is that erecting new statues to replace the ones that have fallen out of favor may not always be a quick and easy process, although perhaps it could become easier given the current momentum behind efforts to replace monuments to the Confederacy and others who sought to uphold white supremacy.

But regardless of how long it may take and who all gets involved, what is clear is that it all must start with two simple questions: Who is and isn’t recognized on our campus? And why?

Christian K. Anderson receives funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to conduct a summer seminar for school teachers on Black lawmakers during Reconstruction.

Read These Next

Researchers are combining drones and AI to make removing land mines faster and safer

Using drones makes detecting land mines safer. Using AI to fuse data from multiple types of sensors…

We designed an AI tutor that helps college students reason rather than give them answers

A 2025 study shows that an AI-based tutor improves learning when it prompts reasoning and is paired…

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…