5 reasons police officers should have college degrees

When it comes to making law enforcement professionals less likely to resort to use of force, higher education goes a long way, research shows.

Following several deaths of unarmed black men at the hands of police, President Donald J. Trump issued an executive order on June 16 that calls for increased training and credentialing to reduce the use of excessive force by police.

The order did not mention the need for police to get a college education, even though higher education was identified in the 2015 President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing as one of six effective ways to reduce crime and build better relations between police and the communities they serve.

As researchers who specialize in crime and punishment, we see five reasons why police officers should be encouraged to pursue a college degree.

1. Less likely to use violence

Research shows that, overall, college-educated officers generate fewer citizen complaints. They are also terminated less frequently for misconduct and less likely to use force.

Regarding the use of force, officers who’ve graduated from college are almost 40% less likely to use force. Use of force is defined as actions that range from verbal threats to use force to actually using force that could cause physical harm.

College-educated officers are also less likely to shoot their guns. A study of officer-involved shootings from 1990 to 2004 found that college-educated police officers were almost 30% less likely to fire their weapons in the line of duty. Additionally, one study found that police departments that required at least a two-year degree for officers had a lower rate of officers assaulted by civilians compared to departments that did not require college degrees.

Studies have found that a small proportion of police officers – about 5% – produce most citizen complaints, and officers with a two-year degree are about half as likely to be in the high-rate complaint group. Similarly, researchers have found that officers with at least a two-year degree were 40% less likely to lose their jobs due to misconduct.

2. More problem-oriented

The 2015 task force recommended community and problem-oriented policing strategies as ways to strengthen police-community relations and better respond to crime and other social problems. Problem-oriented policing is a proactive strategy to identify crime problems in communities. The strategy also calls for officers to analyze the underlying causes of crime, develop appropriate responses, and assess whether those responses are working. Similarly, community-oriented policing emphasizes building relationships with citizens to identify and respond to community crime problems. Research has found that when police departments use community-policing strategies, people are more satisfied with how police serve their community and view them as more legitimate.

Community policing and problem-oriented policing require problem solving and creative thinking – skills that the college experience helps develop.

For example, internships and service-learning opportunities in college provide future police officers a chance to develop civic engagement skills. It also gives them the chance to get to know the communities they will police. Among students who participated in a criminal justice service-learning course working with young people in the community, 80% reported a change from stereotypical assumptions that all of them would be criminals to a better understanding of them as individuals with goals and potential - some not so different from the students’ own dreams. Almost 90% said they had come to understand the community, which they believed would serve them in their criminal justice careers.

Among street-level officers who have the most interaction with the public, having a bachelor’s degree significantly increases commitment to community policing. These officers tend to work more proactively with community members to resolve issues and prevent problems rather than only reacting to incidents when called.

3. Enables officers to better relate to the community

Higher education has been shown to enhance the technical training that police get in the academy or on the job.

For instance, as college students, aspiring or current police officers participate in internships, do community service or study abroad. All of these things have been shown to increase critical thinking, moral reasoning and openness to diversity. College also leads to more intercultural awareness. Taken together, all of these skills are essential for successful policework.

Research has also shown that police officers themselves recognize the value of a college degree. Among other things, they say a college education improves ethical decision-making skills, knowledge and understanding of the law and the courts, openness to diversity, and communication skills. In one study, officers with criminal justice degrees said their education helped them gain managerial skills.

4. Helps officers identify best practices

A college education helps officers become better at identifying quality information and scientific evidence. This in turn better enables them to more rigorously and regularly evaluate policies and practices adopted by their departments.

For example, many departments employ de-escalation tactics that aim to reduce use of force. A critical step in knowing whether an approach is achieving its intended goal is evaluating its impact. Officers who have an understanding of scientific methods, as taught in college, are better positioned to adjust their department’s policies.

5. Builds better leaders

Bringing about meaningful police reform requires transformational leadership. Higher education, including graduate degrees, can enhance the leadership potential of criminal justice professionals and support their promotion through the ranks.

Police officers with at least some college experience are more focused on promotion and expect to retire at a higher rank compared to officers with no college. It should come as little surprise, then, that police administrators, including police chiefs, are more likely to hold college and post-graduate degrees. Leaders with a graduate degree are twice as likely to be familiar with evidence-based policing, which uses research to guide effective policy and practice.

Higher education and police reform efforts are at a critical juncture.

Educated law enforcement professionals will be better equipped to lead much-needed reform efforts. State and local agencies and governments can do more to encourage officers to seek a college degree, including through incentives, like the Nebraska Law Enforcement Education Act, which allows for a partial tuition waiver or the Quinn Bill in Massachusetts, which provides scaled bonuses depending on the degree an officer holds or tuition reimbursement scholarships like those offered by the Fraternal Order of Police. Colleges and universities can help officers acquire the skills needed to help to reestablish trust between our communities and those who are sworn to protect and serve.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

Gaylene Armstrong receives funding from various state and federal granting agencies in support of criminal justice research.

Leana Bouffard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

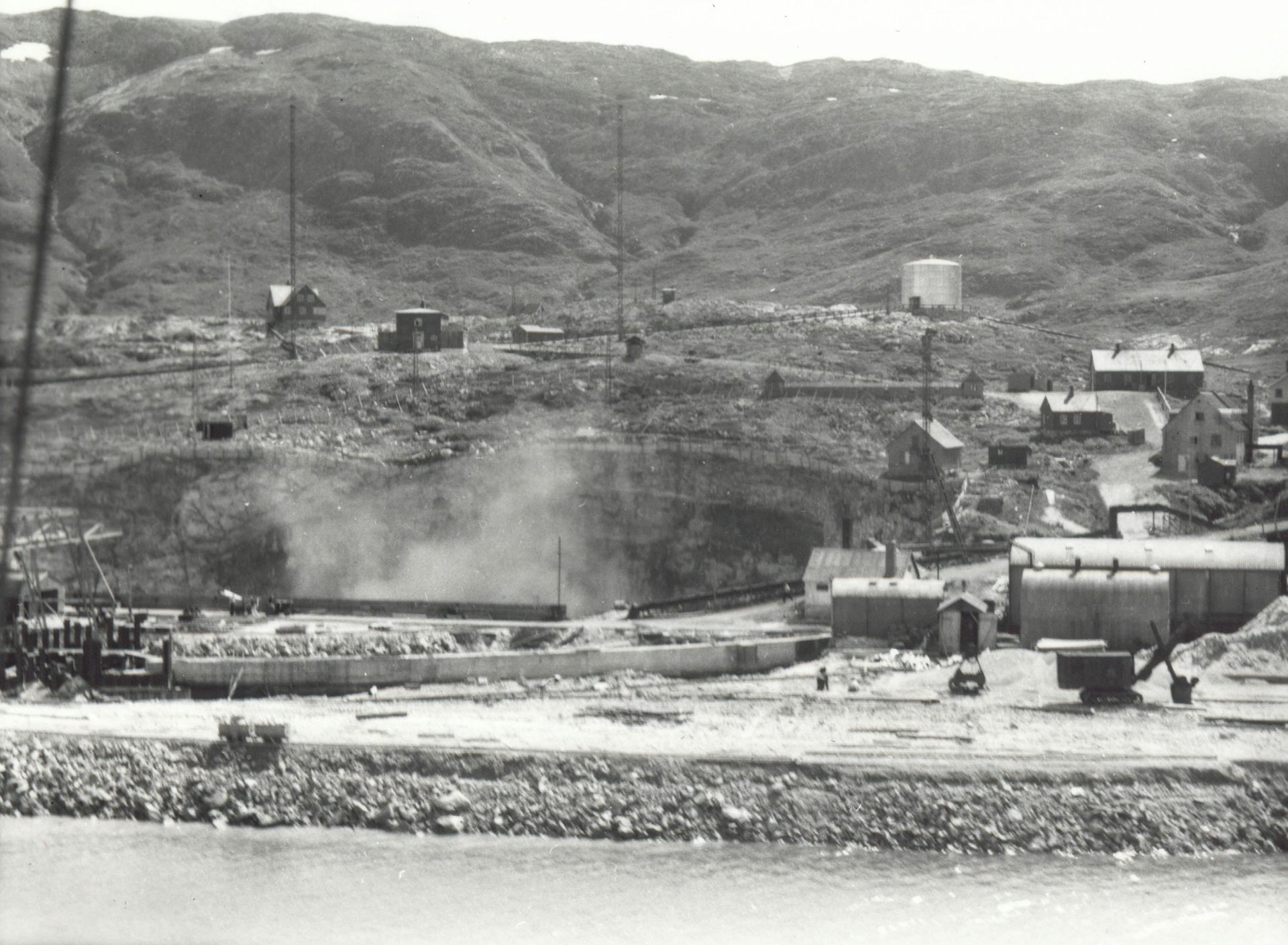

In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

Strategic resources have been central to the American-led global system for decades, as a historian…

Revisiting the story of Clementine Barnabet, a Black woman blamed for serial murders in the Jim Crow

In 1912, a young Black woman’s supposed religious beliefs were quickly blamed to make sense of a terrifying…

3 generations of Black Philadelphia students report persistent anti-Black attitudes in schools

A sociologist explains how Black students in Philadelphia navigate racial prejudice and find affirmation…