The good-guy image police present to students often clashes with students' reality

Some school districts are starting to remove police. A team of researchers explains why that could be a welcome trend.

Eight days after George Floyd was killed during an encounter with Minneapolis police in an incident that sparked protests around the world, Minneapolis Public Schools terminated its contract for the Minneapolis police to provide officers in schools.

“I value people and education and life,” school board chairwoman Kim Ellison told a local newspaper. “Now I’m convinced, based on the actions of the Minneapolis Police Department, that we don’t have the same values.”

On June 4, Guadalupe Guerrero, the superintendent of Portland Public Schools in Oregon, followed suit, saying: “We need to re-examine our relationship” with the Portland Police Bureau.

“The time is now,” Guerrero tweeted. “With new proposed investments in direct student supports (social workers, counselors, culturally-specific partnerships & more), I am discontinuing the regular presence of School Resource Officers.”

Research supports these efforts to limit the number of police officers regularly stationed in schools. Other approaches, such as improving school climate, are better at keeping schools safe.

Further, as researchers who study school safety and the use of police in schools, we recently discovered another reason why taking cops out of America’s schools may be a welcome trend.

Based on our research, school resource officers don’t view their job only as keeping kids safe. They also spend a lot of time trying to make students trust the police and believe that the police are generally good.

School resource officers are sworn police officers who work in schools. They are usually armed and in uniform, and are trained and generally supervised as police officers, not school employees.

The problem we see with that sort of pro-police messaging is that the message is often at odds with some of the violent police behavior students have experienced or seen in their communities.

For example, research on the experiences and perceptions among black students and students from largely black communities finds that they have also learned that the police are an ever-present threat to their freedom and their lives. The all too common scenes of people of color dying at the hands of police reinforce what they’ve learned.

Thus, when the cops they see in their schools are saying one thing but the cops on the street are doing something else, it puts students in a position where an authority figure is asking them to believe something that blatantly contradicts their own reality.

A better way, we think, would be to have educators and police think more critically about the conflict between what police tell students and what they see – and to consider whether police even need to be in schools to start with.

Message versus reality

Consider, for instance, the words of one student we interviewed who told us how his school resource officer’s message contradicts what he sees in the news about the police.

“I always see on the news police officers doing everything to hold people down and stuff and I’m like nope, don’t want to run into them,” the student said. He added that his school resource officer “just makes me think different about them they may be doing the right thing.”

In another instance, a teacher described how a school resource officer justified the arrest of a student’s father, suggesting that the father was at fault for the family’s suffering. “We weren’t out to get your father,” the officer told the student. “Your father broke the law.”

In a different case, a Hispanic student asked whether the school resource officer was going to arrest the student’s mother due to concerns about her citizenship status. The officer dismissed the student’s concern as biased, failing to recognize how law enforcement’s role in actions against undocumented immigrants might have contributed to the student’s worries.

Pro-law enforcement message

About half of all public schools nationwide have police officers in schools, including large proportions of rural (44%), town (58%), suburban (49%) and city (45%) schools.

Over the past several years, we, along with education researcher Samantha Viano of George Mason University, have discovered dozens of instances where school resource officers use their positions of power to deliver pro-law enforcement messages – often to counter the negative news coverage that police have been getting as of late for use of excessive force. The school resource officers in our study, who worked at all levels of K-12 education, from elementary school through high school, consistently described teaching students to trust police as their second-highest priority, safety being the first. They saw negative portrayals of police as unwarranted. One officer argued that “the news media… puts a bad rep on a lot of police officers.”

The school resource officers actively sought to counter negative views about their profession with positive messages about what they do. One officer told us “it’s a PR thing … we’re wanting to make sure that those kids know that, you know, police are not the bad guys.”

To build trust and goodwill, the officers fostered relationships with students, greeted them with high-fives and worked to be approachable.

School leaders reinforced this approach. One district leader stated: “I think that is desperately needed to understand that law enforcement are a positive in our society.”

Alleged anti-police bias

School resource officers, as well as teachers and principals, recognized that not all students came to school with a positive view of police. But, rather than considering how police might contribute to such views, our research shows that they described students as biased against police because of negative news stories.

The officers acknowledged to students that sometimes police need to arrest people or use force. However, they taught students that this happens only when the person is committing a crime. They taught students that incidents of police violence are the result of isolated “bad apple” officers and not true of police in general. And, they explained that students shouldn’t blame police for doing their jobs – even if the person arrested is a loved one.

Moving forward

Where there are schools with officers present, we see a need for school leaders, teachers and school resource officers to allow more critical discussions about policing. This could involve explicitly teaching about police violence, facilitating student-led activism projects or dialogue about police behavior.

As school resource officers seek to build positive relationships with students, they should also recognize that the high-fives they give them at the school door aren’t emblematic of the treatment those children and teens may receive once they leave the school premises. Educators and the police should listen to and validate students’ experiences and acknowledge problems of policing rather than ignore them.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

F. Chris Curran has received funding from the National Institute of Justice and the American Civil Liberties Union for work on school policing.

Aaron Kupchik has received funding from the National Institute of Justice to do research on school policing.

Benjamin W. Fisher has received funding from the National Institute of Justice for work on school violence, including school policing.

Read These Next

Coffee crops are dying from a fungus with species-jumping genes – researchers are ‘resurrecting’ the

Coffee wilt disease has continually devastated farms around the world. Understanding the fungus’s…

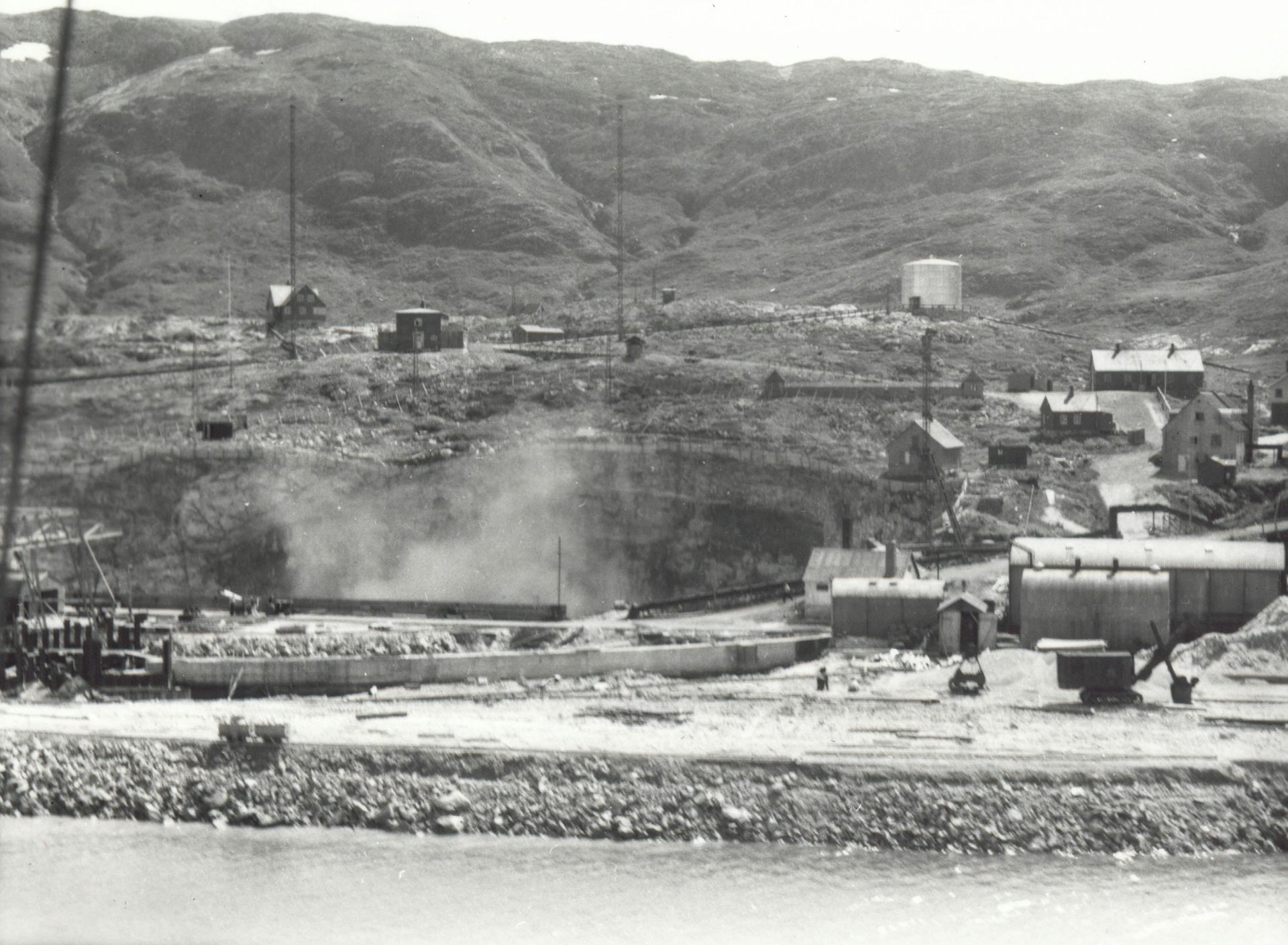

In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

Strategic resources have been central to the American-led global system for decades, as a historian…

Revisiting the story of Clementine Barnabet, a Black woman blamed for serial murders in the Jim Crow

In 1912, a young Black woman’s supposed religious beliefs were quickly blamed to make sense of a terrifying…