To solve the hidden epidemic of teen hunger, we should listen to teens who experience it

Faced with uncertainty over their next meal, teens in a Texas study reveal the various things they resort to in order to put food on the family table.

For many young people, the toughest choice they will ever have to make about food is what to eat at home or what to choose from a menu.

But for Texas high schoolers Tamiya, Juliana, Trisha, Cara and Kristen, the choices they have to make about food are more difficult. For them, the conversation is less about food and more about how to put food on the table.

“It’s kind of hard because like, I know I’m young, and my momma don’t want me to get a job, but it’s really helping out,” Kristin told us for a 2019 study regarding her decision to work as a waitress at a fast food chain. “Because basically, my check is paying for the food we’re going to eat … the tips I made today are what we ate off of.”

Such stories are part of a hidden epidemic that I – a social work scholar – and one of my students, Ana O’Quin, investigated for a recent study about food insecurity among America’s teenagers. Food insecurity, as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, means limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods. It also means the inability to acquire foods without resorting to socially unacceptable means, such as stealing or transactional dating.

The consequences of food insecurity follow teens into the classroom and even reduce their chances of graduation.

According to the most recent federal estimates, 37 million people live in food-insecure households. This includes nearly 7 million young people who are 10 to 17 years old.

The problem of food insecurity is particularly pronounced among African Americans, who collectively are twice as likely as whites to experience food insecurity.

Going without

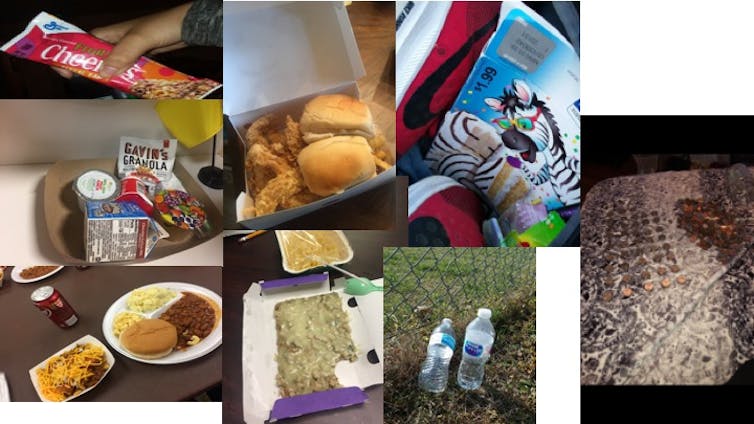

Teens in these households are more likely to skip meals or not eat for a whole day because there was not enough money for food. Some teens drink water, eat junk food or go to sleep instead of eating a meal.

“Most parents will feed you before they feed themselves,” Trisha told us. “When food stamps first come, Mamma cooks a lot. But like a week later, it’s nothing. Maybe cereal, or noodles, sandwiches.”

Juliana added, “We used to always buy rice, because you can buy a lot of it, and it’s cheap. You can buy Spam and rice and that would be the whole meal for the rest of the week.”

While many teens rely on their parents and guardians well into adulthood, we found that these teens rely on themselves before they even become adults. Julianna says she started babysitting at about the age of 12 to help put food on the table.

“Whatever money I would get from that, I would give it to my mamma,” Julianna said.

It’s not uncommon for teens to sacrifice to make sure their mother eats.

For instance, Kristin told us that her thinking goes like this: “I know your health is worse than mine. So mamma make sure you eat. I don’t care … I can scrounge up some food at school.”

Taking risks to eat

The teens we spoke with shared how peers engage in risky behaviors that have long-term consequences. Out of desperation, some teens – rarely but still too often – find themselves shoplifting, stealing, transactional dating, “trading sex” for food or selling drugs to access food. “Stealing is the main thing,” said Cara.

Health impact

Teens typically experience a growth spurt and need more food during adolescence. Without adequate nutrition, teens often experience the short-term effects of food insecurity, such as stomach aches, headaches and low energy. Teens in our study mentioned having a difficult time focusing in class or even staying awake during school.

Food insecurity can result in long-term effects in the following areas:

• Physical health conditions, like asthma, anemia, obesity and diabetes.

• Mental and behavioral health including anxiety, depression, difficulty getting along with peers, substance abuse and even suicidal thoughts.

• Cognitive health such as slower learning rates and lower math and reading scores.

What can be done?

These teens live in households eligible to receive free and reduced breakfast and lunch and food assistance benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the U.S. government’s largest anti-hunger program, which served 40 million in 2018.

Eligible families receive an electronic benefit transfer of funds each month to purchase food, on average US$1.39 per meal.

Teens from our study said they preferred electronic benefit transfer over the stigma of going to a food pantry or other public place to receive food. To address the hidden epidemic of teen food insecurity and its consequences, the teens first suggested increasing food stamp benefits to provide the extra food growing teens need.

The teens in our study also suggested:

• Encouraging teens to participate in school sports or afterschool programs like The Cove or the Boys and Girls Clubs where meals are served.

• Recommending that restaurants participate in food rescue programs like Cultivate that prepare weekend meals for schoolchildren.

• Cultivating gardens at schools or in the community through organizations like 4-H clubs, university extension programs and the Food Project.

• Developing job training programs like the 100,000 Opportunities Initiative to help teens gain skills to break the cycle of poverty and hunger.

Employment desires

Teens like Kristin prefer to work to help put food on the table. While research shows there are benefits of teens working to provide food for their families, it also highlights the trade-offs such as students abandoning school for work.

Young people who experience food insecurity bring a keen awareness to this challenge. It’s time for people who can do something about the problem to listen to what they have to say.

[ Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter. ]

Stephanie C. Boddie and student, Ana O'Quin, received funding from the Center for Public Justice's 2019 Hatfield Prize.

Read These Next

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…