Curious Kids: Who was the first black child to go to an integrated school?

School integration is often thought of as something that took place in the 1960s. But the first black student to desegregate a school by court order was an Iowa girl named Susan Clark in 1868.

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Who was the first black child to go to an integrated school? – Makena T., age 12, Washington, D.C.

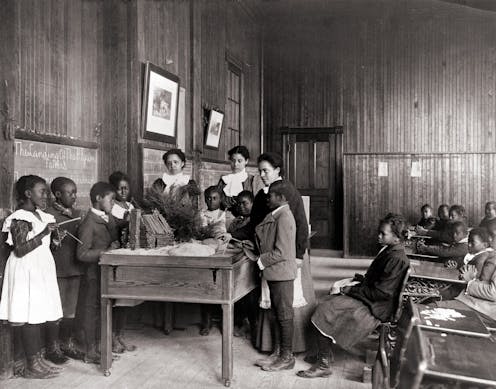

When people think about the time when black people first began to integrate America’s public schools, often they think back to the 1960s.

But history shows the first court-ordered school integration case took place a hundred years earlier, in the 1860s.

In April of 1868, three years after the end of the Civil War, Susan Clark – a 12-year-old girl from Muscatine, Iowa – became the first black child to attend an integrated school because of a court order.

The Supreme Court of Iowa issued that court order when it made its historic ruling in a school desegregation case brought by Susan’s father, Alexander Clark. This was 86 years before the U.S. Supreme Court issued the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, which ordered the desegregation of the nation’s public schools.

In the Iowa case, a judge named Chester Cole ruled that the Muscatine School Board’s racial segregation policy was illegal. The Iowa Supreme Court was the first court in the nation to say that segregation was unlawful.

Up from slavery

Susan Clark’s parents were Alexander Clark and Catherine Griffin Clark. Alexander’s father, John – this would be Susan’s grandfather – was born to a slave owner and an enslaved woman. Both John and his mother were freed after John’s birth. Alexander’s mother, Rebecca Darnes, was the daughter of emancipated slaves, George and Leticie Darnes. Alexander was born free in Pennsylvania in 1826. Catherine Griffin was born a slave in Virginia in 1829, and was freed at the age of three and taken to Ohio.

Alexander and Catherine married in 1848, and set up their home in Muscatine, a small, prosperous town on the Mississippi River. Alexander was a barber and a successful businessman. He was an outstanding speaker and was so active in the Underground Railroad – a secret network that helped slaves escape to freedom – and other civil rights causes that he has been recognized as “one of the greatest civil rights leaders of the 19th century.”

School board wanted segregation

The Muscatine School Board didn’t try to hide the reason it rejected Susan’s application to attend Grammar School No. 2, which was the school closest to where she lived. The school said its decision to keep black and white students segregated was in line with “public sentiment that is opposed to the intermingling of white and colored children in the same schools.” The school board argued that its schools were “separate but equal.” This argument worked in a lot of other courts at the time, including the highest courts in Massachusetts, New York and California. But the argument didn’t work in the Supreme Court of Iowa.

Justice Cole pointed out that the very first words in the Iowa Constitution say “equal rights to all.”

First black graduate

Susan Clark didn’t experience threats and taunts like black children did when they integrated schools in the 1960s. There were only 35 black children in Muscatine at the time.

Susan Clark went on to become the first black graduate of a public school in Iowa – Muscatine High School – in 1871 and served as commencement speaker.

The Muscatine Journal praised Susan’s commencement address, “Nothing But Leaves,” for its “originality,” observing it was “unpretending in style” and had “many excellent thoughts.”

Susan married the Rev. Richard Holley, an African Methodist Episcopalian minister, and their ministry took them to Cedar Rapids and Davenport, Iowa, and Champaign, Illinois. Susan lived a long life, passing in 1925 at age 70, and was buried in Muscatine’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Iowa led the nation

You might wonder why and how the Iowa Supreme Court ruled against segregation at a time when other courts were not doing so.

Each of the four justices on the Iowa Supreme Court was a Republican – the party of Abraham Lincoln – and each had been a strong supporter of the Union cause. Chester Cole was an early advocate for giving black men the right to vote because of their service in the Union Army during the Civil War.

It is important to note that the Iowa Supreme Court never overturned the Clark v. Board of School Directors decision, even after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1896 that segregation was legal under the U.S. Constitution.

Fifty-eight years after ruling that segregation was legal, the U.S. Supreme Court issued the 1954 Brown v. Board decision that desegregated the nation’s public schools. The Brown decision showed how far ahead the Iowa Supreme Court was when it said segregation was illegal nearly a century earlier.

You can learn more about the stories of Susan Clark, Alexander Clark and Justice Chester Cole in this 2019 Drake Law review article, titled Clark v. Board of School Directors: Reflections After 150 Years, and from the electronic study guide on the Clark decision and its historical context.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Russell Ellsworth Lovell II I am a Professor Emeritus of Drake Law School, where I was a full-time member of the Law Faculty for 38 years (including 10 years service as Associate Dean). I retired in 2014. Drake Law School hosted the 2018 Sesquicentennial Celebration of the Iowa Supreme Court's decision in Clark v. Board of Directors (of Muscatine Schools), which is the focus of the piece I have written for The Conversation. I was a principal author of Drake University's grant application to the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, which was successful, and the TMCF was a major sponsor of the Sesquicentennial Celebration. I received no compensation from the TMCF grant, but Drake did reimburse me for a small amount of out-of-pocket expenses I incurred from the TMCF grant. I am a volunteer and co-chair of the Legal Redress Committees for the Iowa-Nebraska NAACP and the Des Moines NAACP; I receive no compensation from the NAACP. The Des Moines NAACP also provided funding to the Clark Sesquicentennial as a co-sponsor. I respectfully submit that none of these affiliations have, in any way, influenced my views about the Clark v. Board case, Susan and Alexander Clark, or Justice Chester Cole. My more extensive views on the Clark decision were set forth in 67 Drake Law Review 175 - 202 (2019).

Read These Next

Venezuela’s fragile forests face rising risks as US pushes for oil and critical minerals and illegal

The Orinoco Basin is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also rich in oil, gold…

How Instagram addictiveness lawsuit could reshape social media – platform design meets product liabi

A lawsuit against Meta and Google avoids the issue of liability for content and focuses on allegations…

Family-friendly workplaces are great − but ‘families of 1’ get ignored

In an era of family-friendly workplaces, how can employers treat single people without kids fairly?