Could a tax on stock trades pay off the nation's student debt?

An economist takes a critical look at a proposal to tax Wall Street to pay off the nation's student debt.

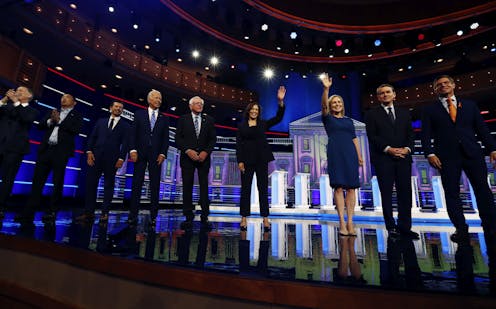

If several of the Democratic candidates for president have their way, student debt will be a thing of the past – at least for current student loan borrowers.

Sen. Bernie Sanders has proposed ambitious legislation that would cancel all student loan debt.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s plan would pay up to US$50,000 in loans for borrowers making less than $100,000, and a reduced amount for those making between $100,000 and $250,000.

Other Democratic candidates have more modest plans for tackling student debt. Candidates including Cory Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand and Pete Buttigieg want to expand the amount that can be forgiven in the federal loan forgiveness program and make more people eligible.

President Trump has weighed in, too, proposing a modified loan forgiveness program that eliminates debt for borrowers that have paid their loans for at least 15 years.

All of these candidates are on to something. The nation’s student debt problem is an issue that needs solving.

What’s the problem with student loan debt?

Some have even called the issue of student debt a “crisis.” Millennials are aging into their 30’s and 40’s with more education than previous generations, but also with higher student debt and less wealth.

And that debt has grown, with graduates owing 62% more than they did a decade ago. Three times as many owe $50,000 or more.

As borrowers pay their debts for 10 years, 20 years or more, they have less freedom to change jobs and cities, less ability to take career risks and, consequently, lower incomes. Workers who take fewer risks also create less innovation and economic growth.

Student debt also means borrowers have less money to spend on other things. For instance, with an average debt payment of close to $400 a month, borrowers may forgo new car and home purchases. Or they may be unable to afford to plan for retirement.

Costs and trade-offs

Sanders’ bill is the most ambitious. It will cost $1.6 trillion to cover debt owed by 44 million Americans, or more than $35,000 per borrower.

As an economist, here are four reasons why I am doubtful that the Sanders plan will work.

1. Taxing stock market transactions may backfire

Sanders plans to pay for his plan with a tax on stock market trades of 50 cents on every $100 worth of stocks traded. There would be lower fees for bond and dividend transactions.

But, as any economist will tell you, taxing transactions will lead to fewer transactions. For example, a similar but smaller tax – 0.2% versus the 0.5% proposed by Sanders – in France appears to have led to a 10% reduction in financial transactions in the short run, but economists debate whether that reduction stuck around in the long term. If there were less buying and selling of U.S. stocks, the tax will bring in less revenue and the government will risk being unable to fully fund their $1.6 trillion commitment.

Sanders says the tax is too low to affect every day investors and would, in fact, only reduce high frequency trading. But Wall Street claims the tax would reduce every investor’s ability to sell their stocks, reducing liquidity in the stock market and pushing investors toward the transactions, like bond purchases, that are taxed at a lower rate.

2. The tax could reduce household wealth

Taxes almost always get passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. In this case, more fees on trade stocks will likely affect the value of the portfolios of American households. The majority of stock value is held by the richest Americans, but more than 60% of Americans have retirement savings, much of which is invested in stocks and bonds. Increased fees and less activity in these markets may cause them to lose value, which could in turn affect retirement savings for Americans across a range of incomes.

3. Loan forgiveness changes how borrowers view risks

For now, the Sanders plan is only a one-time payoff of existing debt. However, future borrowers may consider the potential for future loan forgiveness when deciding how much to borrow. Borrowers will take out more student loans than they would otherwise if they are hopeful the government will bail them out. Economists call this phenomenon moral hazard.

Moral hazard was seen after the financial crisis, when some banks gave even riskier loans after the government covered their losses as the housing market collapsed.

4. The plan benefits the rich more than the poor

Thirty-five percent of student debt is held by individuals with incomes in the top 20th percentile, while only 15% of debt is held by those with incomes in the bottom 20th percentile.

This means that Sanders’ proposal would disproportionately benefit the Americans with the highest incomes.

Ultimately, relieving Americans of at least some of the burden of their student debt should stimulate the economy and lead to economic growth as borrowers’ income is freed up to spend, save and invest. Will this increased spending offset the reduced value in the stock market that will likely follow a tax on trading? Based on what I know as an economist, it’s not something that I would bank on.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]

Melissa Knox does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…

How sewage treatment plants could handle food waste, sparing landfills and the climate

Rather than generating climate-warming emissions and wasting nutrients and energy, food waste can become…