How T.M. Landry College Prep failed black families

T.M. Landry College Prep, facing allegations of abuse, is known for getting students from poor backgrounds into Ivy League schools. An education scholar says the school's focus was misplaced.

Of all the challenges that vex black parents, perhaps none is more frustrating than to be forced to send their children to schools where their children’s talents go unrecognized, overlooked, ignored or even squashed.

As I argue in my book – “Rac(e)ing to Class: Confronting Poverty and Race in Schools and Classrooms” – teaching in a way that recognizes the strengths of black students takes considerable training. This is especially true in a system where the majority of teachers are white and middle class.

As a scholar of race and urban teacher education, I see a major disconnect between what schools offer black students and the realities that black students face outside the classroom.

Given how often public schools fail black children, the allure of a “college prep” school – even if it is in a nontraditional school environment – becomes easy to understand. A school like that is seen not only as an alternative to the regular public schools but as the doorway to the most elite educational institutions of higher education in the nation – and all that earning a degree from one of those institutions entails.

Gateway to elite schools

And so it was with T.M. Landry College Prep – an independent private school located in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana. The school doesn’t list race or ethnicity in its student profile. However, promotional materials and news reports suggest the majority of the student body is black.

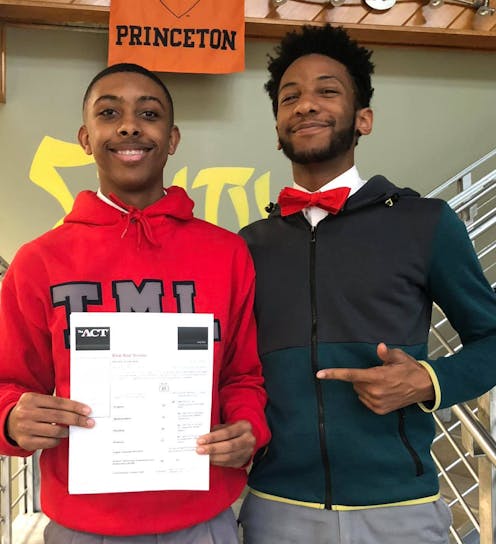

The school began to garner widespread attention in 2017 after students and school officials posted a series of videos of Landry students being accepted into some of the nation’s top colleges and universities – including Ivy League schools. The image of elated black students clad in college sweatshirts as they learned they had been accepted into the likes of Harvard and Yale made for striking theater.

T.M. Landry had seemingly cemented its status as a model school for black students who hail from families that were struggling to make ends meet.

Beset by allegations

Unfortunately, it now appears that this dream school was actually a nightmare.

As reported by The New York Times, the husband-and-wife co-founders of the school – Michael and Tracey Landry – allegedly falsified student transcripts and exaggerated or lied about students’ life stories in order to make them more attractive to college admission committees looking to diversify their student bodies.

The school is also under investigation by Louisiana state police for allegations of abuse. The accusations against Michael Landry range from striking students to making one student eat rat feces.

People are rightly incensed about what the students at T.M. Landry reportedly had to endure.

Beyond the allegations of abuse, there were also academic practices that raise serious questions about T.M. Landry’s approach to educational success. For instance, the high school students spent an excessive amount of time on ACT practice tests – “day after day,” according to The New York Times.

“If it wasn’t on the ACT, I didn’t know it,” Bryson Sassau, a T.M. Landry student who took the ACT three times, told The New York Times as he lamented how ill prepared he was for college.

Rethinking education’s purpose

But even if Sassou and his fellow students at Landry had been prepared for college, would that necessarily make T.M. Landry a good school for black students?

As one of many scholars who studies the interplay of race, culture and education, I believe the true measure of a school’s worth is not the extent to which its students get accepted into elite institutions. But rather, I’d measure a school by the degree to which it inspires students to engage in collective efforts to improve the human condition.

In fairness, T.M. Landry College Prep’s creed includes a line that states: “Commitment to the betterment of self and society as a whole.” The degree to which the school infused that into its daily coursework is questionable.

This is particularly important for black students in the United States, who hail from a population that experiences gross disparities in a broad range of areas, from health and wealth, education and justice, and from infant mortality to life expectancy.

Educational researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings has questioned the overemphasis on test scores. She has stressed the need reframe the way society thinks about education – to go from focusing on the so-called “achievement gap” to an “education debt” that reflects how much more should be invested in the education of children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. I have stressed the need to focus not on achievement gaps but rather on “opportunity gaps” that show inequities in systems, structures and practices, among other factors, that can prevent children from reaching their potential.

Given the unique history that evolves from America’s “peculiar institution” – slavery – and the many ways in which it has impacted black identity, education must also equip black students with knowledge and skills they need to analyze, critique, question and write about the ways in which they’ve been miseducated.

Even at its best – that is, even if the school wasn’t facing allegations of abuse or that it doctored student transcripts and came up with fake sob stories to get them into college – if the school’s focus was primarily concerned with test prep, T.M. Landry was not a truly transformative school that black students need and deserve.

True transformative schools don’t just work to help black students better fit into the existing educational and social system. They don’t want to just contribute another “beat the odds” story about how so called “merit” and “hard work” can help them overcome centuries and decades of class and race inequity and oppression.

Schooling vs. education

What black students need – more than anything else - is less schooling and more education.

Schooling is “a process intended to perpetuate and maintain the society’s existing power relations and the institutional structures that support those arrangements,” as Mwalimu J. Shuiaa states in “Too Much Schooling, Too Little Education: A Paradox of Black Life in White Societies.”

Education, on the other hand, is an emancipatory process of lifelong learning that enables students to study and read the broader society and work to disrupt injustice.

Schools like T.M. Landry that just want to “school” black students well enough to get into the Ivy Leagues so that they can earn a degree, acquire material things and the trappings of success – all the while fitting into the existing power structure – are problematic. Such schools may appeal to black families because of their negative experiences in traditional public schools, but they don’t really enable students to challenge the status quo.

Indeed, as Audre Lorde has argued, the “master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” And as James Baldwin has stressed in his famous “Talk to Teachers,” during these times of anti-blackness, racism, xenophobia and discrimination writ large, it is time to “go for broke” in order to teach black children to break out of the existing social order. In order to do that, educators must radically shift what education is – and who decides what counts as academic and social success.

As of the publication of this article, the school’s co-founders, Michael and Tracey Landry, had stepped down from the school’s board but will continue to teach at the school.

H. Richard Milner IV is Cornelius Vanderbilt Endowed Chair of Education in the Department of Teaching and Learning at Peabody College of Vanderbilt University. He has received funding from the Heinz Endowments and the Grable Foundation.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…