Teachers' activism will survive the Janus Supreme Court ruling

The Janus decision by the Supreme Court is a serious legal and financial blow to unions and their hundreds of thousands of members. But it will not kill public-employee unions or teachers' unions.

The Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Janus v. AFSCME 31 will hurt public employee unions in both membership and funding.

The majority opinion, written by Associate Justice Samuel Alito, said that requiring public employees who are not union members to pay fees to a union for representation compels them “to subsidize the speech of other private speakers” – a union. That, the justices ruled, violates the First Amendment.

This decision essentially turns all of the United States into a “right-to-work” environment for public employees. That means unions in the majority of states can continue to represent teachers, police and other public workers, but those unions can’t require workers to join or pay representation fees. The ruling affects hundreds of thousands of teachers, public health workers and police officers in 21 states from Hawaii to Maine.

As a scholar of the history of post-World War II education policy, I see this decision as an important landmark in the history of teachers unions. The Supreme Court ruling is a serious legal and financial blow, but it will not kill public employee unions, teachers unions – or the ability of teachers to work together to amplify their voices for social change.

The choice for teachers unions

Collective bargaining is an important role for unions, but it’s important to understand that unions have long been about more than that.

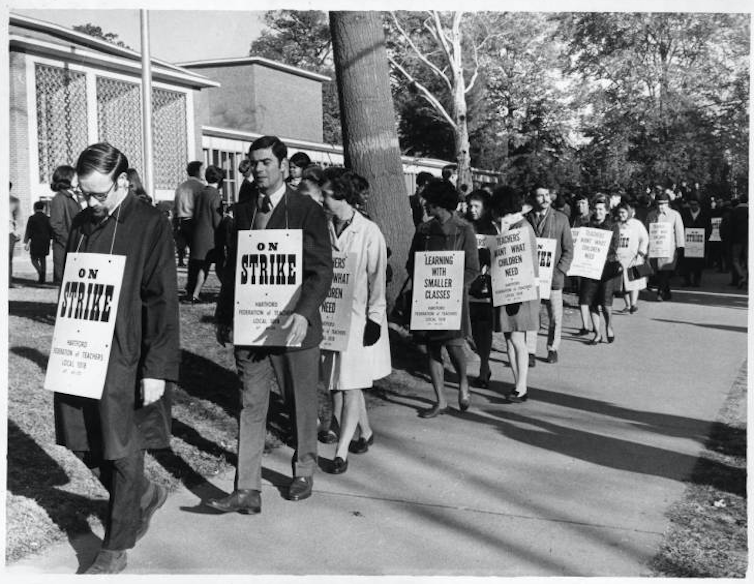

Starting in the 19th century, teachers – who were mostly women – fought for decades to gain the right of union representation. That fight was not just about fair salaries and treatment. There has always been a social and political side of unionism. The first major teachers’ union in Chicago allied with social reformers to sue for the collection of corporate taxes in the early 20th century, for example. The enforcement of those corporate taxes funded schools and city services in general.

Decades later, national teachers’ unions and union leaders often worked in collaboration with civil rights organizations. In the battle over voting rights in Selma, Alabama, teachers led by the Rev. Frederick Reese comprised the first group of professionals to join the voting rights marches, in January 1965.

These two dimensions of union history – advocacy for workers of specific employers and a broader engagement about the terms of politics and the social contract –– have consistently been at play, true of local as well as national unions. Activist unions fight for parental leave and early childhood education – for values, in addition to salaries and a lunch that teachers can take by themselves.

Looking ahead

Activist unions can survive in a “right-to-work” environment.

I know this personally. When I worked in Florida, I recruited dozens of my colleagues to join my university’s faculty union. Since the revision of the state’s constitution in 1968, Florida’s teachers and other public employees have operated under the state’s “right-to-work” provision in the state constitution. In other words, the United Faculty of Florida thus had the same legal context all public employee unions now face after Janus. When promoting membership, I explained what our union did concretely. But many of my former colleagues joined because our union defended values shared by faculty.

This spirit of activism was on display this year as thousands of teachers in West Virginia, Arizona and Oklahoma effectively organized despite having no union. Arizona’s teachers shut down schools for six days. They pushed a conservative legislature and governor into making a down payment on increased funding for schools and teacher salaries.

Like their counterparts in West Virginia and North Carolina, Arizona’s teachers persuaded the public that they were walking out on behalf of their students and on behalf of what education could and should be.

In making the case about more than teacher salaries, Arizona teachers revived a long history of social movement by teachers. The teachers who started the movement to organize the walkout were not leaders of a union, but they made the type of impact on teachers’ lives and public policy that we usually associate with unions.

Legal status is not the only factor that determines what teachers unions and a public workers social movement can accomplish.

In my opinion, those who think the Janus ruling is irrelevant are fooling themselves. So are those who think this decision will kill all public employee unions.

The factors that pushed teachers to unionize in the past century will not go away. The tools at their disposal may change – but the drive to improve their careers and workplaces will continue.

Sherman Dorn does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…

In its hunt for critical minerals, the US is misconstruing what is and is not America’s

There’s a growing interest in mining the ocean seabed for minerals essential to technology. But whose…