'Career ready' out of high school? Why the nation needs to let go of that myth

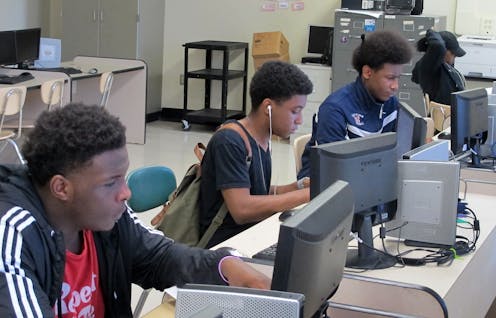

Unlike the days of old, career and technical education in today's high schools doesn't really prepare students for work. Researchers at Georgetown University explain why CTE must be revamped.

Unlike old-fashioned vocational education, high school-level career and technical education doesn’t really prepare people for jobs directly after high school. While the stated end goal of K-12 education in America is for students to be “college and career ready,” the reality is the existence of career-ready high school graduates is a myth. The expectation that high school produces career-ready adults in a 21st century economy is unrealistic and counterproductive.

While there have been efforts to revive vocational training in high school, it has become clear that, for today’s students to be prepared for tomorrow’s jobs, all pathways must lead to a credential with labor market value, such as a certificate, associate’s degree or bachelor’s degree. Good jobs that only required a high school education, in blue-collar fields and the military, have declined, while the jobs that took their place in fields like health care, information technology and business services require more than a high school education.

On average, CTE courses comprise only 2.5 out of the 27 credits high school students earn, not nearly enough coursework to prepare students for an entry-level job with a career ladder. What’s more: CTE “concentrators” – that is, students who take at least three CTE courses – and who don’t go on to obtain a college degree, certificate or certification earn 90 cents more per hour than nonconcentrators.

This matters because – as we’ve shown through research here at the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce – half of young adults are failing to successfully launch their careers. If we fail to recognize that the game has changed and that high school is no longer enough, we will also fail to prepare future generations for tomorrow’s jobs.

Not your parents’ high school

The movement away from the tightly focused job training in high school – and toward the richer mix of academic and career-related learning in CTE – began in 1983 with the publication of “A Nation at Risk.” That seminal report urged the nation’s schools to adopt a set of new academic basics that stripped K-12 education of its vocational mission and watered down academic track in favor of a highly standardized academic college-prep curriculum for all students. The shift was driven by both changing economic and political realities – specifically, the postindustrial restructuring of the American economy and the criticism that vocational education put advantaged and disadvantaged students on separate educational tracks.

At the same time, it became clear that high school degrees no longer provide enough general or career-specific education to prepare young people for good jobs.

Since the 1980s, the relationship between education and careers has changed in other profound ways. The narrow job-specific training provided by traditional vocational courses, such as auto mechanics, was no longer enough in an economy where skill requirements were constantly rising at a fast pace. In modern economies, narrow vocational preparation at the high school level leaves workers without enough general education to land middle-class jobs.

Toward a college prep curriculum

Furthermore, in an increasingly diverse society, many policymakers in the ‘80s and '90s became convinced that narrow vocational and academic tracking by race, class and gender was inefficient and unfair. This tracking left poor and black students in shop class and women in home economics – a reality that was characteristic of the comprehensive high school curriculum that had been in place since the end of WWII. Such tracking created indefensible differences in education and career opportunities for people from different backgrounds.

With vocational education and the watered down education track removed, the K–12 system became the host for a standards-based academic curriculum designed to prepare students for college and life in a modern democracy – but not for work in a particular job.

As a result of the curriculum reforms since 1983, there is no longer much room for career preparation in high school. For instance, an average of 22 of the 26 credits required for a high school degree are reserved for academic courses necessary to meet state graduation standards in subjects such as English, math and science.

Because of the shift from vocational to academic preparation, high school curriculums have become one-size-fits all. They no longer have a direct relationship with most college majors or careers. Career preparation has shifted to the postsecondary sphere. Even the much heralded Career Academies haven’t been shown to land students in living wage jobs, even eight years after graduation.

CTE programs – commonly in health care, agriculture, and business – that gradually replaced the old-style job training provide little actual job training. Compared with traditional vocational training programs, CTE is available to a much broader diversity of high school students by race and class. As a result, CTE today is much less likely to be accused of tracking by race, class and gender.

Modern CTE programs have multiple functions. CTE programs provide hands-on learning models. They also provide employability skills such as communication, teamwork, problem solving, initiative and self-management. Those skills are portable across occupations and different work settings. Modern CTE programs also help foster career exploration across in-demand career fields. But there is substantial room for improvement.

How CTE must change

We first have to recognize that the current vision is only working for half of our young adults. That is, less than half of young adults earn a bachelor’s degree, associate’s degree or industry-recognized certificate [postsecondary credential] [https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.pdf] – the current standard for career readiness – by the age of 30. The advantaged half of our high school students [earn] [http://www.pellinstitute.org/downloads/publications-Indicators_of_Higher_Education_Equity_in_the_US_2016_Historical_Trend_Report.pdf] college degrees, and most, if not all, move on to successful career pathways.

Our research shows that among those who earn college degrees and certificates, the vast majority make more than the average high school graduate.

Recent developments in federal policy, such as the Every Student Succeeds Act, are not enough to meet the challenge of helping the forgotten half of young Americans. The act includes the words “career readiness,” but the career-ready high school graduate only exists in the collective imagination. Similarly, reauthorizing the Perkins Act, the chief federal funding source for CTE, would be a positive step. Ultimately, however, the major reforms must take place at the state or regional level.

In the best cases, a handful of states, like Delaware and Tennessee, are successfully developing pathways to in-demand careers. Middle school students are exploring careers that suit their talents and interests. High school students are gaining employability skills and practical work experience in career fields so that they are ready to shop for postsecondary programs in their junior year.

We must scale up this new model in more states and cities across the country and invest more in programs that connect education to work. Only then will we reach the forgotten half of young adults who aren’t making it in today’s economy.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

Jesse Jackson’s misdiagnosis of Parkinson’s is common – new genetic discovery could lead to treatmen

People typically die from progressive supranuclear palsy within 7 to 10 years. There is currently no…

I was teaching virtue and knowledge while lying on the side

While rationalizing deception is easy to do, developing the virtue of truthfulness is not.