Reading to young kids improves their social skills − and a new study shows it doesn’t matter whether

New research shows that parents who read to their 6- to 8-year-olds nightly boost their children’s creativity and empathy.

In 2024, 51% of families read aloud to their very young children, while 37% read aloud to their kids between the ages of 6 and 8 years old.

Some parents have said they stop reading aloud to their school-age children because their kids can read on their own.

I’m a neuroscientist with four children, and I wondered whether children might be losing more than just the pleasure of listening to books read aloud. In particular, I wondered whether it affected their empathy and creativity.

A simple idea from the literature

I have studied and written about empathy and creativity as part of my personal effort to better understand how to be a good parent. I have found that empathy and creativity aren’t talents you’re born with or without. They are skills that respond to practice, just like learning to play piano.

But my children weren’t being taught either empathy or creativity in elementary school. And the data showed that young people’s empathy and creativity may have dropped over the past few decades.

Empathy isn’t just about being nice. It’s a superpower that helps children predict behavior and navigate social situations safely. It makes them better at reading faces and emotional cues.

And creativity is essential for self-control and problem-solving. It’s much easier to regulate your behavior if you can imagine multiple solutions to a problem instead of fixating on the one thing you’re not supposed to do.

About 10 years ago, I started making some changes at home to ensure that my children got these skills.

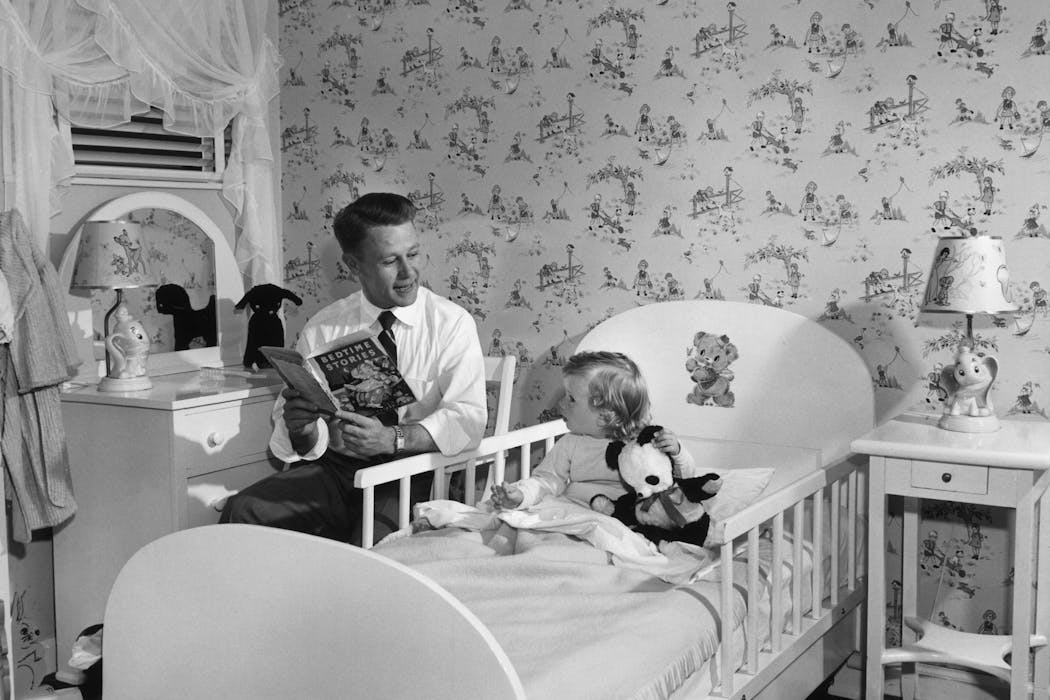

Setting aside 15 minutes at night was sometimes the only one-on-one time I had with each kid, with bedtimes of 7:30, 7:45, 8:00 and 8:15 p.m. It was precious to me. I wondered whether using conflicts in bedtime stories as teachable moments would help them develop more empathy for others and boost their creativity.

I wrote in 2016 about how I think my children became more empathetic when we paused at times during a book to ask: “How do you think this character feels?” and “What would you do?”

But no one had tested this experiment on a broader scale.

Testing the idea

Beginning in 2017, four colleagues and I recruited 38 families in central Virginia with children ages 6 to 8, which is an age when kids are navigating social relationships and experiencing intense brain development. All of the children in our study were somewhat independent beginning readers or they could read independently. In our study, caregivers read one storybook nightly for two weeks.

I chose seven illustrated books: “The Tooth Fairy Wars,” “Library Lion,” “A Letter for Leo,” “Stuck with the Blooz,” “Cub’s Big World,” “Nugget and Fang” and “A New Friend for Marmalade.” There was nothing special about these books except that they all contained some sort of social conflict – and my kids gave them a thumbs-up.

They were about, among other characters, a polar bear cub who becomes separated from his mother in the snow, and a boy who hid his teeth from the tooth fairy.

Half the families in our study read a book each night straight through without pausing. The other half paused at one conflict point per story to ask two reflection questions. For example, when the tooth fairy stole the tooth Nathan desperately wanted to keep, they asked, “How would you feel if you were Nathan?” If the child answered, parents just listened. If not, they waited 30 seconds before continuing.

Before and after two weeks, we tested children’s empathetic ability to understand what others might be thinking and how they are feeling. We also tested creativity using the alternative uses task, which asked kids to generate creative ideas, such as thinking of unusual uses for a paper clip or listing things with wheels.

A boost in empathy either way

After just 14 bedtimes with books, we found – as our 2026 research shows – that children whose parents paused for questions got better at understanding others’ perspectives. But so did children whose parents just read straight through.

We found that what scientists call cognitive and overall empathy improved significantly in both groups between childen’s initial visit and our follow-up visit two weeks after they read the books for a week.

This may be because it is easier to quickly develop cognitive empathy – meaning when you put yourself in someone else’s shoes – as compared to developing emotional empathy, or feeling what others feel. Emotional empathy involves different brain regions and likely requires longer to change deeply rooted emotional processing patterns.

A creative approach

After two weeks of bedtime reading, children in both groups got better at creative thinking. We used a standard creativity test that measures the number and the originality of responses when children were asked to think of uses for everyday objects. For example, if asked about a brick, a common answer would be to build a wall, while a more original response might be to grind it up to make red chalk.

But the children whose parents paused for questions generated significantly more ideas overall.

Their responses delighted me: They suggested using a paper clip as wire in a potato clock, to help put on a doll’s shoes, or to simply see what sound it makes hitting the floor.

We also noticed that the younger kids came up with more original ideas than the older ones. This matches other research showing that creativity may fade as children grow up and they prioritize fitting in with others more than thinking differently.

What we still need to learn

Our study had limitations: We did not have a comparison group that did not read at all. And most families had a higher income, with 92% of families earning more than $50,000 per year.

Future research could address this gap and also investigate whether the benefits we found persist past two weeks – and whether they translate into real-world kindness.

But importantly, we found no gender differences in our study. The practice works equally well for boys and girls. And even though the majority of our families said they already read regularly to their children, this practice still worked to boost empathy and creativity.

Bedtime stories are about more than routine

As a neuroscientist, I know the elementary school years are a particularly powerful window when children experience intense formation of new brain connections.

These 15 minutes of reading aren’t just about preparing kids to sleep or teaching them to decode words. They’re building neural pathways for understanding others and imagining possibilities. With repeated practice, these connections strengthen, just like practicing piano.

In a world designed to pull families toward screens, bedtime reading remains a refuge where parent and child share the same imaginative space.

But the pressure’s off for parents: You don’t have to read in any special way. Just read.

Erin Clabough is affiliated with Neuro Pty Ltd.

Read These Next

GLP-1 drugs may fight addiction across every major substance, according to a study of 600,000 people

GLP-1 drugs are the first medication to show promise for treating addiction to a wide range of substances.

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…