AI could worsen inequalities in schools – teachers are key to whether it will

Under-resourced schools are less likely to support teachers in implementing AI technology to best serve learning.

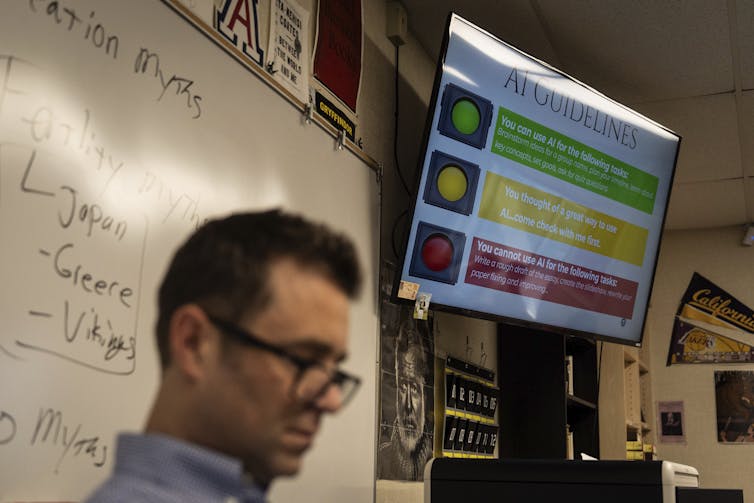

Today’s teachers find themselves thrust into a difficult position with generative AI. New tools are coming online at a blistering pace and being adopted just as quickly, whether they’re personalized tutors and study buddies for students or lesson plan generators and assignment graders for teachers. Schools are traditionally slow to adapt to change, which makes such rapid-fire developments especially destabilizing.

The uncertainties accompanying the artificial intelligence onslaught come amid existing challenges the teaching profession has faced for years. Teachers have been working with increasingly scarce resources – and even scarcer time – while facing mounting expectations not only for their students’ academic performance, but also their social-emotional development. Many teachers are burned out, and they’re leaving the profession in record numbers.

All of this matters because teacher quality is the single most important factor in school influencing student achievement. And the impact of teachers is greatest for students who are most disadvantaged. How teachers end up using, or not using, AI to support their teaching – and their students’ learning – may be the most crucial determinant of whether AI’s use in schools narrows or widens existing equity gaps.

We have been conducting research on how public school teachers feel about generative AI technologies.

The initial results, which are currently under review, reveal deep ambivalence about AI’s growing role in K-12 education. Our work also shows how inadequate training and unclear communications could worsen existing inequalities among schools.

A ‘thought partner’ for busy teachers

As part of a larger project examining AI integration in education, we interviewed 22 teachers in a large public school district in the United States that has been an early and enthusiastic adopter of AI. The district serves a multilingual and socioeconomically diverse student population, with over 160 languages spoken and approximately three-quarters of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

The teachers who participated in our study spanned elementary, middle school and high school grade levels, and represented a variety of subject areas, including science, technology, engineering and mathematics, social studies, special education, and culturally and linguistically diverse education. We asked these teachers to describe how they first encountered generative AI tools, how they currently use them, and the broader shifts they have observed in their schools. Teachers also reflected on both the opportunities and challenges of using AI tools in their classrooms.

Mirroring a recent survey finding that AI has helped teachers save up to six hours per week of work, the teachers in our study pointed to AI’s ability to create more space in the day for themselves and their students. Turning to AI for help writing lesson plans and assessments not only saves time, but it also gives teachers a tool for brainstorming ideas, helping them feel less isolated in their work. One high school teacher with over 11 years’ experience reflected:

“The most significant benefit that AI has brought to my life as a teacher is having work-life balance. It has decreased my stress 80-fold because I am able to have a thought partner. Teachers are really isolated, even though we work with people constantly … When I’m exhausted, it gives me support and help with ideas.”

Why lack of training matters

However, not all teachers felt well-equipped to benefit from AI. Much of what they told us boiled down to a lack of resources and other professional support. An elementary school classroom teacher explained:

“It’s just a lack of time. We don’t really get much planning time, and it would be a new tool to learn, so we would have to take the time personally to learn how to use it and where to find everything.”

Many teachers underscored the need for – and current lack of – professional development offerings to help them understand and integrate AI into their teaching.

Research on previous waves of technological innovations shows that under-resourced schools serving disadvantaged students are typically the least well-equipped to provide teachers with the professional support they need to make the most of new technologies.

Because well-resourced schools are far more likely to offer such support, the introduction of new technologies in schools tends to reinforce existing inequities in the education system.

When it comes to AI, well-resourced schools are best positioned to give teachers time, support and encouragement to “tinker” with AI and discover how and whether it can support their teaching and learning goals.

‘You need a relationship’ to learn

Our research also uncovered the importance of preserving the relational nature of teaching and learning, even – or perhaps especially – in the age of AI. As one middle school social studies teacher observed:

“A machine can give you information, but most students we know are not able to get information from something that’s just printed out for them and put it into their heads. You need a relationship. Some kids can do online school or read a book and teach themselves, but that’s like 2%. Most kids need a social environment to do it.”

Here again, prior research shows us that teachers in well-resourced schools are better equipped to introduce new technologies in ways that augment rather than undermine the relational dimensions of teaching and learning. And again, teachers are crucial in determining how and whether AI, like all new technologies, is used to support their teaching and student learning.

That’s why we believe the practices established during this current period of rapid AI development and adoption will profoundly influence whether educational inequities are dismantled or deepened.

Grounded in the classroom

Going forward, we see the need for research to examine how generative AI is changing teachers’ practice and relationship to their work. Their input can inform practices that empower teachers as professionals and advance student learning.

This approach requires adequate institutional support at the school and district levels. It also means listening to the real experiences of teachers and students instead of responding to the promised benefits touted by education technologies companies.

Katie Davis has received funding from the Spencer Foundation.

Aayushi Dangol does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…

There aren’t enough geriatricians – here’s how older adults can still get the right care

A few simple strategies can help older adults convey their needs to their health care provider.

Minneapolis united when federal immigration operations surged – reflecting a long tradition of mutua

Minnesotans from all walks of life, including suburban moms, veterans and protest novices, have bucked …