Mindfulness is gaining traction in American schools – but it isn’t clear what students are learning

Understanding the nuances of what mindfulness can look like in a classroom can help educators, parents and policymakers decide whether it belongs in their schools.

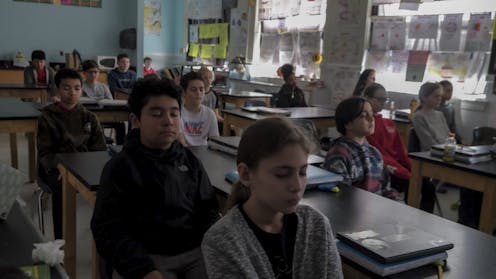

Writing, reading, math and mindfulness? That last subject is increasingly joining the three classic courses, as more young students in the United States are practicing mindfulness, meaning focusing on paying attention to the present moment without judgment.

In the past 20 years in the U.S., mindfulness transitioned from being a new-age curiosity to becoming a more mainstream part of American culture, as people learned more about how mindfulness can reduce their stress and improve their well-being.

Researchers estimate that over 1 million children in the U.S. have been exposed to mindfulness in their schools, mostly at the elementary level, often taught by classroom teachers or school counselors.

I have been researching mindfulness in K-12 American schools for 15 years. I have investigated the impact of mindfulness on students, explored the experiences of teachers who teach mindfulness in K-12 schools, and examined the challenges and benefits of implementing mindfulness in these settings.

I have noticed that mindfulness programs vary in what particular mindfulness skills are taught and what lesson objectives are. This makes it difficult to compare across studies and draw conclusions about how mindfulness helps students in schools.

What is mindfulness?

Different definitions of mindfulness exist.

Some people might think mindfulness means simply practicing breathing, for example.

A common definition from Jon Kabat-Zinn, a mindfulness expert who helped popularize mindfulness in Western countries, says mindfulness is about “paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, nonjudgmentally, in the present moment.”

Essentially, mindfulness is a way of being. It is a person’s approach to each moment and their orientation to both inner and outer experience, the pleasant and the unpleasant. Fundamental to mindfulness is how a person chooses to direct their attention.

In practice, mindfulness can involve different practices, including guided meditations, mindful movement and breathing. Mindfulness programs can also help people develop a variety of skills, including openness to experiences and more focused attention.

Practicing mindfulness at schools

A few years ago, I decided to investigate school mindfulness programs themselves and consider what it means for children to learn mindfulness at schools. What do the programs actually teach?

I believe that understanding this information can help educators, parents and policymakers make more informed decisions about whether mindfulness belongs in their schools.

In 2023, my colleagues and I conducted a deep dive into 12 readily available mindfulness curricula for K-12 students to investigate what the programs contained. Across programs, we found no consistency of content, teaching practices or time commitment.

For example, some mindfulness programs in K-12 schools incorporate a lot of movement, with some specifically teaching yoga poses. Others emphasize interpersonal skills such as practicing acts of kindness, while others focus mostly on self-oriented skills such as focused attention, which may occur by focusing on one’s breath.

We also found that some programs have students do a lot of mindfulness practices, such as mindful movement or mindful listening, while others teach about mindfulness, such as learning how the brain functions.

Finally, the number of lessons in a curriculum ranged from five to 44, meaning some programs occurred over just a few weeks and some required an entire school year.

Despite indications that mindfulness has some positive impacts for school-age children, the evidence is also not consistent, as shown by other research.

One of the largest recent studies of mindfulness in schools found in 2022 no change in students who received mindfulness instruction.

Some experts believe, though, that the lack of results in this 2022 study on mindfulness was partially due to a curriculum that might have been too advanced for middle school-age children.

The connection between mindfulness and education

Since attention is critical for students’ success in school, it is not surprising that mindfulness appeals to many educators.

Research on student engagement and executive functioning supports the claim that any student’s ability to filter out distractions and prioritize the objects of their thoughts improves their academic success.

Mindfulness programs have been shown to improve students’ mental health and decrease students’ and teachers’ stress levels.

Mindfulness has also been shown to help children emotionally regulate.

Even before social media, teachers perennially struggled to get students to pay attention. Reviews of multiple studies have shown some positive effects of mindfulness on outcomes, including improvements in academic achievement and school adjustment.

A 2023 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cites mindfulness as one of six evidence-based strategies K-12 schools should use to promote students’ mental health and well-being.

A relatively new trend

Knowing what is in the mindfulness curriculum, how it is taught and how long the student spends on mindfulness matters. Students may be learning very different skills with significantly different amounts of time to reinforce those skills.

Researchers suggest, for example, that mindfulness programs most likely to improve academic or mental health outcomes of children offer activities geared toward their developmental level, such as shorter mindfulness practices and more repetition.

In other words, mindfulness programs for children cannot just be watered down versions of adult programs.

Mindfulness research in school settings is still relatively new, though there is encouraging data that mindfulness can sharpen skills necessary for students’ academic success and promote their mental health.

In addition to the need for more research on the outcomes of mindfulness, it is important for educators, parents, policymakers and researchers to look closely at the curriculum to understand what the students are actually doing.

Deborah L. Schussler receives funding from Spencer Foundation.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…

The cost of casting animals as heroes and villains in conservation science

New research shows how these storytelling choices can distort science – and how to move beyond them.