Hip-hop can document life in America more reliably than history books

There’s an impulse by universities and media to inaccurately document hip-hop’s history. The genre is, in part, a response to that imprecision, a professor of hip-hop writes.

Describing my 2017 appointment as a faculty member, the University of Virginia dubbed me the school’s “first” hip-hop professor. Even if the job title and the historic nature of the appointment might have merited it, the word was misleading.

Kyra Gaunt, a Black woman who is a foundational figure in the study of hip-hop, worked as a professor of ethnomusicology at the University of Virginia from 1996 to 2002. Her book “The Games Black Girls Play,” which focuses on Black music practices, was published in 2006. I cited her in my work and in the interview I gave before accepting the job.

Also cited in my doctoral work, presented in my interview with the University of Virginia, was scholar Joe Schloss, who worked at the school from 2000-2001. In 2009, he wrote “Foundation: B-boys, B-girls, and Hip-Hop Culture in New York.” And in 2014 he wrote “Making Beats: The Art of Sample-Based Hip-Hop.”

After pushback from readers online, UVA Today amended its original headline documenting my appointment and added Gaunt’s contributions to the article.

As a rapper and scholar, I have experienced and seen misleading hip-hop stories that highlight an impulse to inaccurately document the genre’s history and present. I raised this issue recently in a TikTok “office hours” video – part of a series in which I respond to audience questions from the vantage of hip-hop art and research.

Misleading hip-hop stories

After Johns Hopkins University announced that Lupe Fiasco had been hired to teach rap there in fall 2025, some online platforms, including The Root, incorrectly reported on his assignment.

They described his upcoming job as the first instance of a rapper ever hired as a professor at a university.

This is obviously incorrect. I’m a rapper who since 2017 has worked as a professor of hip-hop while releasing music, which was part of the basis for my earning tenure in 2023. Besides this, I’m certain there were rappers with university teaching jobs before me.

The trend of misrepresenting hip-hop history isn’t unique to communications from places such as Johns Hopkins University or the University of Virginia.

In 2024, the publisher of musician Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson’s “Hip-Hop is History” described it as “the book only Questlove could write: a singular, definitive history” of hip-hop.

Questlove’s book is not, as the publisher claims, a definitive history. It might more accurately be described as Questlove’s take on hip-hop history, or a memoir. Without this necessary distinction, unknowing readers might misinterpret the publisher’s claims.

Questlove writes about finally coming to appreciate Southern rap in the 2000s. But Southern rap history predates Questlove’s appreciation by decades. It doesn’t begin when someone like him finally recognizes its importance.

Similarly, hip-hop doesn’t begin when it’s finally recognized by an exclusive institution or when someone gets a degree for it.

Making hip-hop history

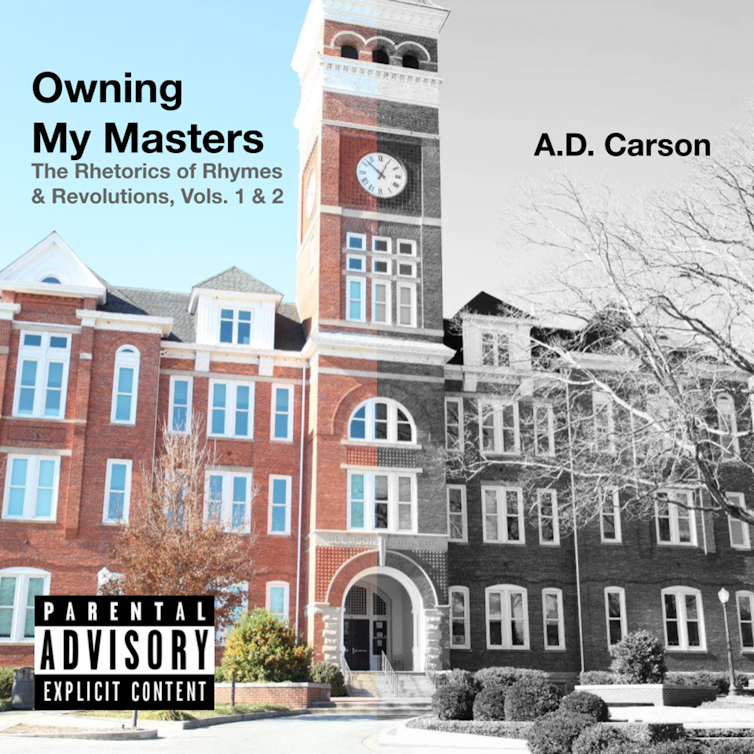

I published these concerns as academic questions in 2017 in an album called “Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics of Rhymes & Revolutions.” The project served as my doctoral dissertation.

“Owning My Masters (Mastered)” is the next phase of the dissertation album project. Published in 2024, it contains new audio, video, images and historical context. It’s published with University of Michigan Press through the same process of an academic book.

“Owning My Masters (Mastered)” demonstrates how hip-hop resists the ways American history often excludes Black resistance, Black achievement, Black storytelling and, ultimately, Black people.

But the exclusion that my work highlights is muted when the seeming novelty of my job appointment or my dissertation album are the focus. When I’m asked if I’m the first person to earn a Ph.D. for making a rap album, I try to answer more expansively to avoid misleading anyone, or ignoring what might be more informative.

It’s also important to understand the barriers that might have made a project like mine impossible before 2017. These include technological barriers that made recording and releasing music prohibitively expensive. And, more specific to hip-hop, it involves a mistrust based on racist history that prevented students from even proposing such a project.

No such “first” happens without the unsung work of others creating the conditions to make it possible.

Learning from hip-hop

Hip-hop’s documentation should not repeat the same flaws of the recording of American history, which can omit important people and events, and which can misrepresent the legacies of racism and systemic violence.

Undeniably, I believe important hip-hop texts, albums and moments should be studied and documented with academic rigor. But this should not solely focus on “firsts,” record sales or prestigious awards.

Such stories fail to accurately illustrate that hip-hop is as much about how people live day to day as it is about how institutions use it to bolster credibility or how companies make money off it.

Important aspects of hip-hop’s diverse culture are excluded when the ordinary is overlooked.

Creating hip-hop is one among the many ways Black people have persevered in the U.S.

Universities and other exclusionary institutions helped sustain – and, in certain ways, continue to benefit from – hellish conditions like those created by slavery.

Hip-hop is, in part, a response to this history.

At its best, hip-hop documents American life more reliably than American history.

Some academic publishers have started to embrace this reality.

My 2020 album “i used to love to dream” may be noteworthy as the first rap album to be peer-reviewed and published with an academic press. More importantly, its contents are about historic erasure of Black people and Black history in my hometown, Decatur, Illinois.

Hip-hop’s popularity, its constant revision and its accessibility make it a powerful vehicle for disrupting inaccurate, exclusionary and fabricated tales passed off as objective facts.

The genre has documented events such as the Tuskegee syphilis study – the 40-year experiment, conducted without informed consent, on Black men by the U.S. Public Health Service to study the effects of the disease when left untreated.

Hip-hop has also cataloged tragedies such as the 1921 Tulsa race massacre – a two-day assault by white mobs on their Black neighbors – and the 1995 Million Man March, a large gathering of Black men in Washington, D.C.

The media ecosystem in which hip-hop has thrived is also steeped with the scapegoating of its art and artists. This scapegoating is weaponized by critics to devalue the culture.

It seems unwise to me to trust institutions such as universities and the media to determine what’s deemed culturally significant. Along with influencers and podcasters who benefit from hip-hop, they can learn valuable lessons from it.

Their ability to determine what’s deemed culturally significant is especially problematic if their choices are primarily in exchange for revenue or credibility. If hip-hop is viewed as a cultural inheritance, then its value – and what’s considered historically important – may be better arbitrated by people in the culture, not outside forces.

A.D. Carson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl show is part of long play drawn up by NFL to score with Latin America

Reggaeton star’s comments on ICE have added to a conservative backlash to NFL’s choice of entertainment.…

Whether it’s Valentine’s Day notes or emails to loved ones, using AI to write leaves people feeling

When you outsource romance, there’s a hidden emotional cost.

Stroke survivors can counterintuitively improve recovery by strengthening their stronger arm – new r

Rehabilitation from stroke has traditionally focused on improving the function of the most severely…