How parents can support a child who comes out as trans – by conquering their own fears, following th

A psychologist and expert on gender diversity explains strategies for creating a healthy environment for trans or nonbinary kids.

Young transgender, or trans, people face high rates of anxiety, depression and suicide. These elevated mental health risks largely stem from external factors such as discrimination, victimization and – most especially – family rejection rather than from being trans.

Em Matsuno, a research fellow at Palo Alto University, is currently developing and testing an online training program called the Parent Support Program to help parents better understand and support trans youth. They talked with The Conversation U.S. about their findings and how parents can be better advocates – and avoid common missteps – when a child identifies as trans or nonbinary.

What are common challenges parents with trans kids face?

A big one is fear. Parents fear for their child’s safety. For example, they fear their kid will be bullied, so they may say, “No, I don’t want you to wear that to school.” Or if they don’t have knowledge about trans identities, they may feel overwhelmed or not know what to do. And they worry about messing up themselves – saying or doing the wrong thing.

Another barrier is the beliefs and attitudes that parents may have. Parents may have grown up learning misconceptions about gender. For example: the belief that one’s sex assigned at birth – which is typically based on anatomy – is the same thing as their gender, or that gender is strictly male or female.

If extended family or their community is conservative, the parents themselves can experience rejection from others as well. People will tell them it’s bad parenting if they let their kid transition. Sometimes parents have to risk being rejected by their loved ones, and it can put them in a difficult position as well.

What does the research say about parental support?

There was a 2016 study that showed trans children who were supported by their parents had similar mental health outcomes as a cisgender control group.

Certainly, there have been studies about trans youth having depression or suicidal ideation. As a result, some people think that being trans makes someone more likely to suffer from mental health risks. But really what we see is that it’s not about being trans but whether you’re supported or not.

One of the studies I worked on looked at different types of social support for trans youth – their friend/peer group, the trans community and their family. Of those three, family support was the strongest predictor of depression, anxiety and resilience. It’s unfortunate because a lot of trans people lose their family support and have to rely on others, but family has the greatest impact.

Online resources advise parents to support a trans child by using their pronouns, advocating for them, educating themselves and showing unconditional love. What would you add or emphasize?

Get your own support. A lot of times parents say they’re 100% supportive and accepting, and yet they still feel feelings – sad, or anxious – and that’s OK. It doesn’t mean you’re not supportive. But sharing all your emotional difficulties with your kid can make them feel like a burden or that they are causing you all this distress. If parents can’t find other parents in their local community, there are online support groups. And get professional support if you can.

What common myths or disinformation do you find most troubling?

The main one is “rapid onset gender dysphoria.” It sounds like a medical term, but it’s not used in trans health whatsoever and is based in faulty research. This often manifests itself in the idea that, “Oh my God, all of a sudden my child is trans. They must be influenced by peers.”

A lot of time kids reach puberty and all of a sudden there are feelings of discomfort. Or maybe it was happening before but they weren’t sharing it with a parent, so it feels sudden to the parent but not to the child.

There’s also a lot of disinformation around gender-affirming medical care, which is a big stressor to a lot of parents. There’s this fear: “What if they change their minds?”

Cases of regret after transitioning are extremely rare. As for puberty blockers, they are reversible and low-risk. Often, trans people don’t know what’s right for them until they try some things out. Yes, there are risks to medical interventions, but there are also significant risks associated with continued gender dysphoria.

Why are more kids today identifying as trans?

Trans and nonbinary people have been around for all of time across all cultures and continents. So it’s not a new thing. But there’s been an erasure of that history.

Now there’s more visibility, more acceptance, and younger generations are also learning earlier on about trans identities. They have what trans actress and activist Laverne Cox calls “possibility models,” where they can think, “Oh, this is an option for me.” For a lot of trans people my age or older, that wasn’t a thing we knew about.

What can parents say to show support when a trans child comes out?

Parents can recognize their kid’s bravery and show gratitude by saying, “Thank you for letting me know.” Also, explicitly say you love them. Trans kids fear rejection when coming out, so very explicit support is important.

Common reactions are to say, “No, you’re confused. You’re just gay/lesbian. Are you sure?” Or asking too many questions, which kind of puts the kid on trial: “How did you know? When did you know?” They fire all these questions and the underlying message is “I don’t believe you” or “I don’t approve.”

A better approach is to say, “Is it OK for me to ask some questions, or do you need some time?” Parents can also ask their kid, “How can I support you?” With younger kids, they might give some examples: “Do you want me to use ‘he’ when I refer to you, or not? What sounds good to you?”

Any final advice for parents?

Learn to tolerate ambiguity, uncertainty and fluidity. Parents often want to know who their child is going to be, with certainty, stability and consistency. That rigidness comes from anxiety.

But things won’t always be clear. Allow your child to come to their own answers. I think with kids there’s a lot of exploration, so things can change and that’s OK. Openness from parents allows them to be who they are.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

Em Matsuno receives funding from the American Psychological Foundation.

Read These Next

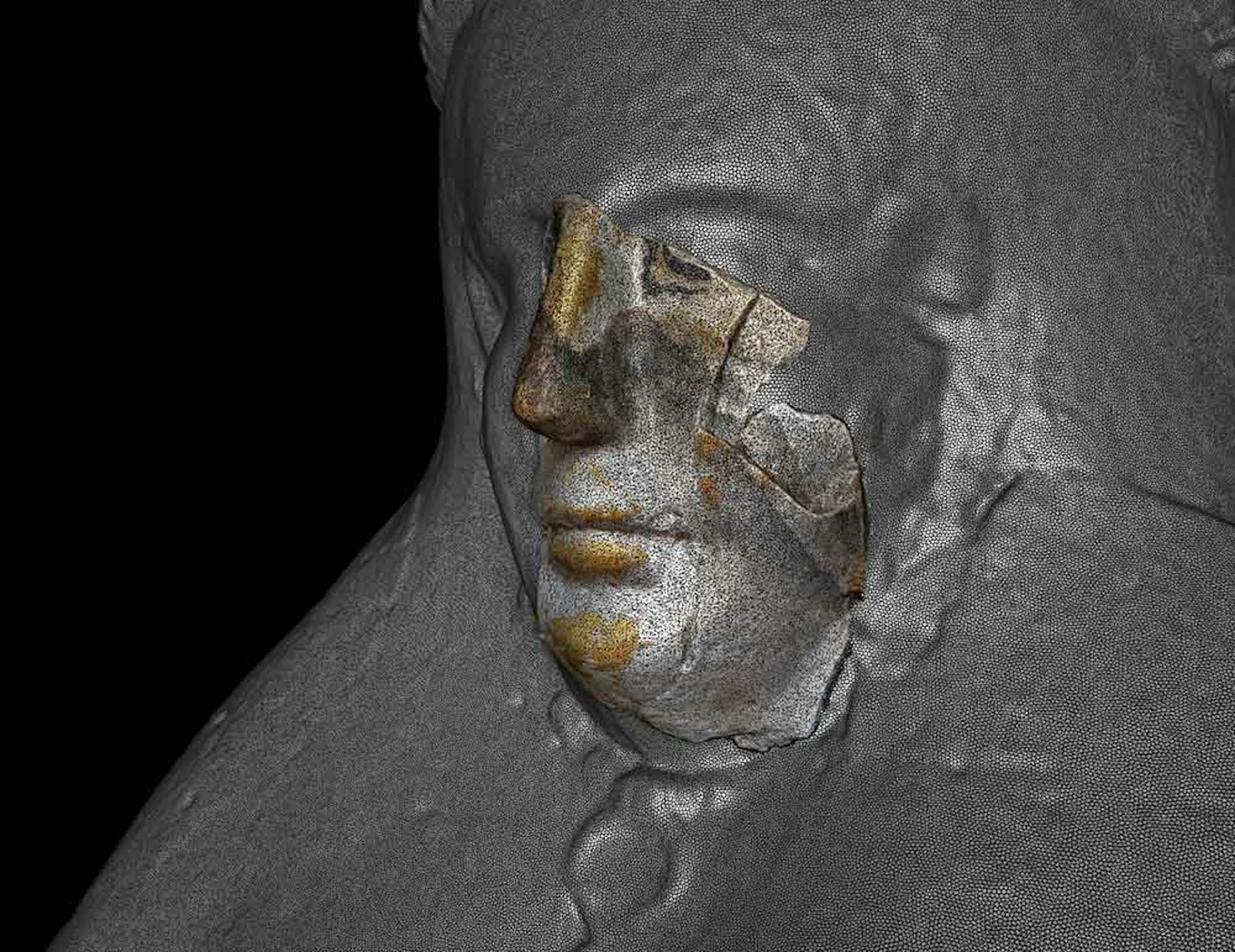

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…

The intensity and perfectionism that drive Olympic athletes also put them at high risk for eating di

Athletes in sports where weight and body image come into play, such as figure skating and wrestling,…

Colorectal cancer is increasing among young people, James Van Der Beek’s death reminds – cancer exp

Colon cancer symptoms can be subtle. While lifestyle changes can help reduce your risk, open communication…