How US Education Secretary nominee Miguel Cardona can stop the teacher shortage

Four experts weigh in on ways to replenish the US teacher workforce and curb burnout.

Editor’s note: Miguel Cardona – President Joe Biden’s choice for secretary of education – faces several urgent and contentious priorities, including reopening schools safely, addressing systemic racism within schools, and reversing the ever-growing teacher shortage. Here, four experts explain how to recruit more people to become educators in the nation’s public schools.

1. Increase pay and reduce class sizes

Bob Spires, associate professor of education, University of Richmond

The teacher shortage has become a crisis in the United States. In 2018, there was an estimated shortage of over 100,000 K-12 teachers. Meanwhile, the demand for K-12 teaching jobs is expected to continue to increase 5% per year through 2028.

Part of the reason for the shortage has to do with pay and working conditions. On average, teachers make roughly 20% less than other college graduates, according to research from the Economic Policy Institute, a think tank that focuses on worker issues. A majority of teachers work additional jobs – either within or outside their schools – to supplement their pay.

Meanwhile, class sizes continue to grow, which teacher unions say negatively affects teachers and students, despite statements to the contrary by former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. Peer-reviewed research bears out that smaller classes are academically, socially and economically beneficial, especially to low-income and minority students.

To curb the shortage, I believe educational leaders and policymakers must take proactive steps at the local, state and federal levels to increase pay and resources for teachers, and alleviate pressure by reducing class sizes.

2. Improve morale and recruit diverse teachers

Doris A. Santoro, professor of education, Bowdoin College

During the pandemic, teachers’ work has been filled with uncertainty and anxiety. Their ways of finding meaning and value as educators have been upended through necessary safety measures that have radically altered their work.

There are no romantic “before times” for most public school educators. Before COVID-19, teachers were reporting ever-increasing levels of dissatisfaction. Schools were already facing continuing teacher shortages, with one estimate as high as 109,000 teachers working without certification in the U.S. in 2017-18. High teacher turnover both disrupts student learning and can degrade the work environment for those who remain.

These conditions may indicate the demoralization of a profession. And yet the profession could become better appreciated as a result of this pandemic. Families are learning firsthand about the demands of teaching as many students learn from home.

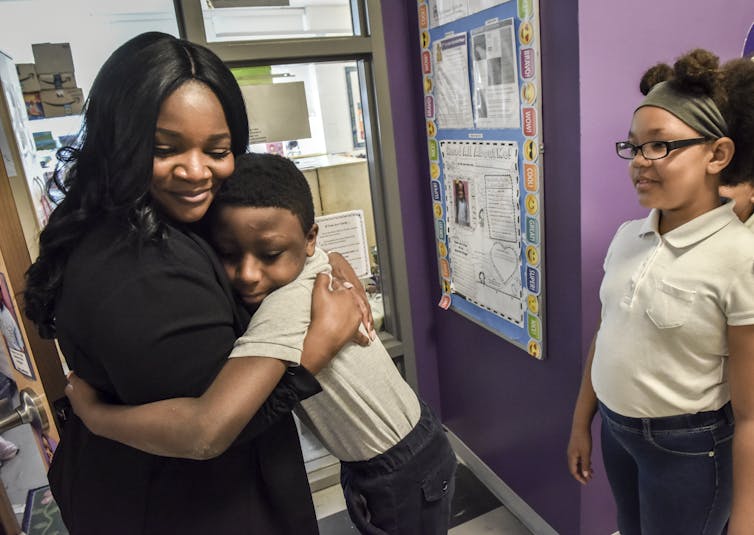

Significant state and local efforts are underway to recruit educators to eliminate the teacher shortage. Some of these efforts focus on attracting teachers who are Black, Indigenous or other people of color. Nationwide, only 20% of teachers identify as people of color, while the population of students of color is over 50%.

Policymakers, education leaders and teachers will need to confront the historic and current reasons for these shortages, including the mass dismissal of Black teachers and principals after Brown v. Board of Education, and classroom practices that leave many teachers of color feeling devalued and alienated.

3. Bring back joy

Diane B. Hirshberg, professor of education policy at the Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage

For several decades now, teachers have been judged on how well their students do on standardized tests.

These efforts have led teachers to use lessons that are narrow and often scripted and that focus mostly on core subjects.

For many teachers, this has taken joy out of what they do.

Giving teachers a canned curriculum and requiring them to follow a schedule and materials developed by people from a different state – or by a big publishing house – can leave teachers feeling as if their own expertise is not recognized or valued. Also, this takes the creativity out of teaching and connecting with students, and diminishes the gratification that comes from seeing their efforts and expertise transform the lives of their students.

Reversing the teacher shortage, in my view, will require Secretary Cardona to push for a system that fosters innovation, rewards expertise in teachers’ careers and uses standardized tests to inform – but not dictate – teacher practice. This requires collaboration among teacher education institutions, states and the Department of Education to transform both teacher preparation and classroom practice. It will require significant investment and patience, but I believe the payoff both for students and the economy will be profound.

4. Build education leadership

Richard L. Schwab, professor of educational leadership and dean emeritus, University of Connecticut

To boost student achievement and teacher morale, research shows you need highly educated and experienced school principals and district leaders.

Thriving businesses invest heavily in leadership development. They commit to training employees who show leadership potential. As in business, effective leaders in education require the right skills and proper support.

Researchers have identified five components of effective principal training programs. They include a coherent curriculum, supervised experiences, active recruiting, cohort structure and continuous engagement with participants.

Examples of programs working with local school districts to do it differently include ours at the University of Connecticut Administrator Preparation Program, University of Washington’s Danforth Educational Leadership Program, University of Denver’s Ritchie Program for School Leaders and the Urban Educational Leadership Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago. They are highly selective and seek to recruit high-potential district educators. Their faculty includes university scholars teaching alongside seasoned practitioners, and they offer extensive clinical placements for participants, who must demonstrate competence as instructional leaders.

Secretary Cardona – who was himself an adjunct professor in Connecticut’s APP program – can help expand such programs nationally, for example by creating seed grants that encourage school-university partnerships and making graduate student loans forgivable to help qualified teachers pursue leadership positions.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Diane B Hirshberg's research on teacher supply, demand, turnover and salary issues in Alaska has been supported by the Alaska State Legislature and the University of Alaska. Other research on education policy issues has been funded by the U.S. Department of Education, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Ford Foundation. Diane Hirshberg was founding director of the Center for Alaska Education Policy Research.

Doris Santoro is a Fellow with the National Education Policy Center.

Richard L. Schwab is faculty member with the Department of Educational Leadership in the Neag School of Education where the UCAPP program mentioned is located.

Bob Spires ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

Read These Next

How a largely forgotten Supreme Court case can help prevent an executive branch takeover of federal

An FBI raid on a Georgia elections facility has sparked concern about Trump administration interference…

The intensity and perfectionism that drive Olympic athletes also put them at high risk for eating di

Athletes in sports where weight and body image come into play, such as figure skating and wrestling,…

Trump says climate change doesn’t endanger public health – evidence shows it does, from extreme heat

Climate change is making people sicker and more vulnerable to disease. Erasing the federal endangerment…