Huge numbers of the formerly incarcerated are unemployed, but there are some promising solutions

Nearly half of formerly incarcerated Americans remain jobless for at least a year. But there are some creative solutions to this problem.

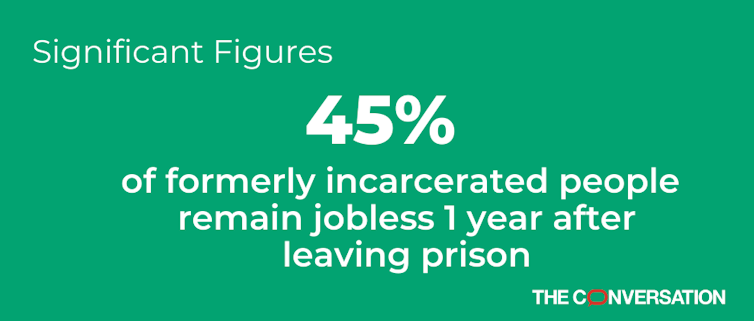

People who have been incarcerated face major challenges finding work after their release. About 45% of formerly incarcerated Americans were unemployed one year after leaving prison, according to a multiyear study the Brookings Institution released in 2018.

This is far higher than U.S. joblessness levels, even during the coronavirus pandemic. The overall U.S. rate spiked to 14.7% in April 2020, receding to 6.7% by December – nearly twice where it stood at the end of 2019.

Three factors essential to a successful transition from prison are employment, housing and transportation, and no one can afford stable housing or reliable transportation without employment. I’m researching two innovative ways to combat unemployment among the formerly incarcerated.

One approach relies on social enterprises, organizations that pursue a social mission while seeking to earn money. These organizations employ formerly incarcerated people for short periods of time. Some examples include Homeboy Industries, the world’s largest gang rehabilitation and reentry program, and Center for Employment Opportunities, the largest reentry employment provider in the country.

The other method, exemplified by the Prison Entrepreneurship Program, is to have business professionals teach people who are incarcerated how to become entrepreneurs so they can launch their own businesses once they leave prison. These programs provide the skills, knowledge and connections needed to succeed as entrepreneurs.

Formerly incarcerated entrepreneurs include Coss Marte, who runs a fitness company; Teresa Hodge, who founded a Baltimore-based nonprofit focused on financial literacy, inclusive entrepreneurship and community engagement; and Marcus Bullock, who created an app that turns photos into postcards that get delivered to individuals who are incarcerated.

People who participate in social enterprises and prison entrepreneurship programs tend to earn more money and are less likely to return to prison than their peers.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

This research was supported by CTSA award number UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibilities of the author and do not necessarily represent official views of NCATS or the National Institutes of Health.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

Jesse Jackson’s misdiagnosis of Parkinson’s is common – new genetic discovery could lead to treatmen

People typically die from progressive supranuclear palsy within 7 to 10 years. There is currently no…

Kurdish gains in Syria could disappear without international support − just as they did in Iraq deca

Despite risks, Kurds in Syria have the best chance in a generation to protect their national rights.…