Trump's decade-old audit illustrates why the IRS targets the working poor as much as the rich

Because the rich often have complicated deductions that dabble in the gray areas of tax law, it's simply easier to audit the straightforward taxes of the working poor

The New York Times’ exclusive on President Donald Trump’s taxes contains a lot of startling new findings.

A few noteworthy examples: He paid only US$750 in federal income tax in 2016 and 2017 – and nothing at all in 10 of the previous 15 years; he took massive income tax deductions for property tax payments on a New York estate he apparently uses for personal reasons; he paid consulting fees to family members; and he took $70,000 in business deductions for haircuts.

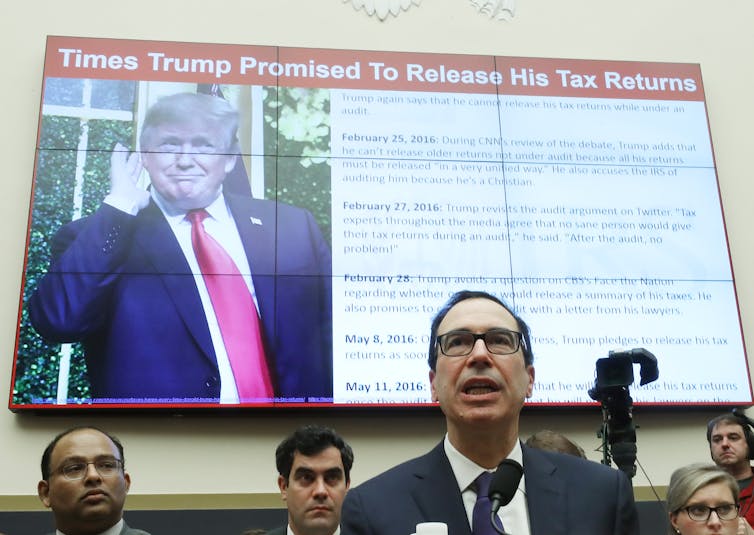

The report also zeroed in on a fact that has been well known for many years yet in my mind overshadows all of the other discoveries: Trump’s taxes are under audit and have been so since at least 2011. Trump claims that’s why he can’t release his taxes, though the IRS itself says that’s not the case. He also says he has paid “millions of dollars” in taxes in recent years.

Why is it taking so long to audit Trump’s taxes, when the IRS usually wraps up its audits within a year?

As a tax law expert, I believe a reason Trump’s audit is taking so long is related to the IRS’s practice of targeting the working poor at rates comparable to the wealthy. It’s hard to reel in the rich and often easier to focus on the poor.

The gray areas of tax law

Tax law is often perceived as an exercise in crunching the numbers. The taxpayer – or an accountant – simply plugs in data from her various W-2s and 1099s, and out comes a figure. Some tax preparation services even show the taxpayer the real-time effect of each entry on the amount of tax owed.

In reality, tax law has plenty of gray areas, particularly for business owners, in which tax law depends on subjectively judging why a person did what he or she did.

When someone acts for business reasons, they should be able to deduct their expenses. As the saying goes, “You have to spend money to make money.” The federal income tax is a net income tax, meaning it respects that old saying and applies only to earnings that exceed costs. If someone is acting for personal reasons like consumption or leisure, a tax deduction is generally not allowed.

Uncovering the motives behind the activities of any person requires a lot of information and difficult analysis, but for someone like Trump, whose personality is his business, the task is exponentially harder.

For instance, is Trump’s Seven Springs estate in New York business or personal property? If it’s for business, property taxes paid on it are fully deductible. If it’s personal property, only $10,000 of the property taxes could be deducted, thanks to Trump’s own Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. The answer depends on a lot of factors, such as how he promotes the property, what types of improvements he makes and what he does while there. Despite some contradictory statements from his sons, The New York Times suggests that Trump has treated the Seven Springs estate as business property, which would allow him to fully deduct the taxes on the estate.

Another gray area is the $26 million he claims in consulting fees, including ones reportedly paid to family members such as his daughter Ivanka. To determine if consulting fees paid to a family member are actually nondeductible gifts, the IRS must examine what she was asked to do and whether the fees were reasonable. It is unclear from The New York Times story what exactly Ivanka was tasked with doing to earn the almost $750,000 in fees Trump deducted.

As for Trump’s $70,000 in haircuts, to determine if they were deductible, the IRS must understand whether they were unique to his job on “The Apprentice.” Inherently personal expenses – things like grooming, meals and commuting – are incredibly difficult to deduct. Trump would have to demonstrate that his business motives completely outweighed his personal ones. In other words, he would have to show that he would not have gotten haircuts but for his business. Since he deducted the cuts, we can presume his hair would have gone unkempt without the show.

Easier targets

Compounding the difficulty of sorting out these gray areas, the IRS is operating on a shoestring budget, despite research showing that a dollar of investment in the IRS yields more than a dollar in tax collections. Auditors must stretch their budgets to uncover the information they need and then make difficult judgment calls.

The IRS’s limited resources mean that auditors end up focusing their attention on cases with more straightforward issues and more accessible information. That’s why lower-income individuals receiving the earned income tax credit were audited at a 1.2% rate in 2016, the most current year of mostly complete data, comparable to the audit rate of roughly 1.5% for individuals earning over $500,000.

Typically, EITC audits are resolved within a year. That’s because examiners can look for objective facts, such as how many children are in the home, rather than sorting out subjective motives behind expenses. Often computers can quickly flag errors, making for more open-and-shut cases.

In addition, as my research has shown, state and federal governments already have a lot of information about individuals receiving public assistance, such as the earned income tax credit. Auditors don’t have to spend their limited resources getting information out of EITC recipients.

While auditing the poor may be easier than targeting the rich, auditing wealthier individuals is likely to do much more to close the tax gap – the difference between what is owed to Uncle Sam and what is actually collected – which the IRS most recently estimated at about $381 billion. Because most misreported income comes from cases where the taxpayer alone controls the information about the income, the IRS might collect more underpayments if it had more resources for auditing the rich.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Letting the big fish go

Taxpayer privacy protections make it impossible to know exactly why Trump is being audited. But the difficulty of sorting out these gray areas of law while Trump holds most of the relevant information almost certainly has contributed to the length of the audit.

If nothing else, the reporting on Trump’s taxes highlights that taxpayers like him are the biggest fish but the hardest to catch, particularly when you have a cheap rod. IRS audits have instead focused on smaller fish downstream.

Hayes Holderness does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…