Can capitalism solve capitalism’s problems?

As capitalism's image crumbles, many of the world's biggest companies are trying to give it new life by showing it can mean more than just making money.

Capitalism is in trouble – at least judging by recent polls.

A majority of American millennials reject the economic system, while 55% of women age 18 to 54 say they prefer socialism. More Democrats now have a positive view of socialism than capitalism. And globally, 56% of respondents to a new survey agree “capitalism as it exists today does more harm than good in the world.”

One problem interpreting numbers like these is that there are many definitions of capitalism and socialism. More to the point, people seem to be thinking of a specific form of capitalism that deems the sole purpose of companies is to increase stock prices and enrich investors. Known as shareholder capitalism, it’s been the guiding light of American business for more than four decades. That’s what the survey meant by “as it exists today.”

As a scholar of socially responsible companies, however, I cannot help but notice a shift in corporate behavior in recent years. A new kind of capitalism seems to be emerging, one in which companies value communities, the environment and workers just as much as profits.

The latest evidence: Companies as diverse as alcohol maker AB InBev, airline JetBlue and money manager BlackRock have all in recent weeks made new commitments to pursue more sustainable business practices.

The purpose of business

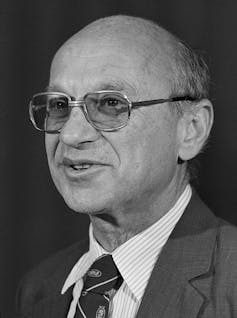

Nearly 50 years ago, the economist Milton Friedman proclaimed that the sole purpose of a business is “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”

Within a decade, Friedman’s claim became accepted wisdom in corporate boardrooms. The era of “shareholder primacy capitalism” had begun.

One result has been remarkable growth in the stock market. But critics argue companies and the “shareholder value theory” are also complicit in exacerbating many economic, social and environmental problems, such as income inequality and climate change.

They also note that putting profits first actually harms shareholders in the long run by encouraging managers to take actions that may eventually reduce earnings.

The rebellion

Many consumers, workers and socially conscious investors have also noticed these shortcomings and increased pressure on corporations to change.

For starters, more Americans no longer find it acceptable for companies to exclusively seek profits. A 2017 poll found that 78% of U.S. consumers want businesses to pursue social justice issues, while 76% said they would refuse to buy a product if the business supported an issue contrary to their beliefs. Almost half the respondents said they had already boycotted a product for that reason.

Workers increasingly expect their employers to share their values. A 2016 study found that most Americans – particularly millennials – consider a company’s social and environmental commitments when deciding where to work. Most would also be willing to take a pay cut in order to work for a “responsible” company – and are demanding their current employers behave that way.

For example, workers at online furniture company Wayfair recently walked out when they learned it had sent beds to detention centers at the U.S.-Mexico border. More than 8,100 Amazon employees signed an open letter supporting a shareholder resolution urging the retailer to do more to address climate change.

Finally, investors are becoming more socially aware and putting more of their money behind businesses that behave in sustainable and responsive ways. At the beginning of 2018, portfolio managers held US$11.6 trillion in U.S. assets using environmental, social and governance criteria to guide their investments, up from $2.5 trillion in 2010.

Laurence Fink, founder and CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, summed up the growing sentiment when he said in 2018, “To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society.”

The corporate response

Presumably realizing how important these constituencies are to their bottom lines, businesses are paying attention.

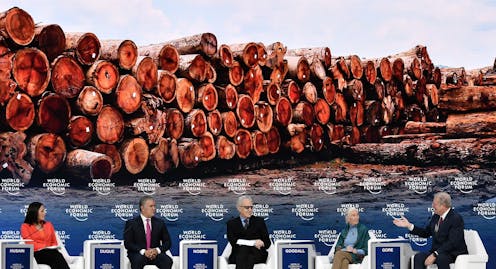

Shareholder capitalism is this year’s theme at Davos, the global gathering of the world’s elite in the Alps. And last year, the leaders at some of the world’s largest companies said that they are ditching shareholder-first capitalism and instead embracing a corporate purpose that seeks to serve all constituents. The sentiment is hardly isolated.

Dick’s Sporting Goods, Kroger, Walmart and L.L. Bean, for example, responded to growing concerns over mass shootings by restricting the sale of guns. Procter and Gamble, a major sponsor for U.S. Soccer, expressed support for the quest of the women’s team for equal pay and donated $500,000 to help narrow the pay gap with men.

Airlines including American, United and Frontier refused to knowingly fly children separated from their parents at the border following outrage over the Trump administration’s policy. And even though Amazon shareholders rejected the worker-supported shareholder resolution described above, Amazon set stronger goals for reducing its carbon footprint after the resolution was introduced.

These actions have sometimes hurt the bottom line. The decision to restrict gun sales cost Dick’s Sporting Goods $150 million. Delta lost a $50 million tax break in Georgia after severing ties with the NRA.

But these and other companies didn’t back down. The CEO of Dick’s Sporting Goods explained that when something is “to the detriment of the public, you have to stand up.”

Companies are also setting tougher social and environmental goals for themselves and then reporting their successes and failures. Tesla, Unilever, Nike and Whole Foods are among nine companies with annual revenues of at least $1 billion that “have sustainability or social good at their core.”

In 2018, 86% of Standard & Poor’s 500 companies reported on their environmental, social and governance performance and achievements, up from less than 20% in 2011.

And companies have found that putting more emphasis on social justice can pay off. Unilever, for example, said in 2017 that its “sustainable living” brands, such as Ben & Jerry’s, Dove and Hellmann’s, are growing much faster than its other brands. Companies with the best scores on their sustainability reports generally perform better financially than those with lower scores.

The end of shareholder capitalism?

Skeptics can be forgiven for believing these corporate “changes” are not real or are simply public relations stunts designed to appeal to a new generation.

Businesses can, of course, say they will be responsible citizens while doing the opposite. Few sustainability reports in the United States are externally audited, and the companies are asking us to take them at their word.

Even if they are well-meaning, intentions are not enough to create systemic change. A 2017 study showed that many companies with climate change goals actually scaled back their ambitions over time as the reality clashed with their lofty goals.

But businesses can’t afford to ignore their customers’ wishes. Nor can they ignore their workers in a tight labor market. And if they disregard socially responsible investors, they risk both losing out on important investments and facing shareholder resolutions that force change.

The shareholder value doctrine is not dead, but we are beginning to see major cracks in its armor. And as long as investors, customers and employees continue to push for more responsible behavior, you should expect to see those cracks grow.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on July 24, 2019.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ]

Elizabeth Schmidt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

The greatest risk of AI in higher education isn’t cheating – it’s the erosion of learning itself

Automating knowledge production and teaching weakens the ecosystem of students and scholars that sustains…

Tahoe avalanche: What causes snow slopes to collapse? A physicist and skier explains, with tips for

An avalanche during a heavy, wet snowstorm in the Sierra Nevada killed at least eight skiers on a guided…

How deregulation made electricity more expensive, not cheaper

Deregulation promised competition but delivered middlemen instead.