Nonprofits that scrimp on overhead aren't necessarily better than those spending more

A study that compared Habitat for Humanity affiliates found that what nonprofits are doing may matter more than how much they’re spending.

Americans are obsessed with doing more with less. So it may not surprise you to hear that when donors, foundations and watchdog organizations choose causes to support, they often focus on overhead ratios – or how much charities spend on expenses such as information technology and office space.

But this measuring stick has drawbacks.

Getting by on the smallest budget possible without skimping on salaries, staffing and equipment is hard, if not impossible, to do. Many philanthropic and nonprofit leaders agree that not all overhead spending is inherently bad. But no consensus has emerged yet around any alternatives.

As a result, charities are tempted to forgo things they need, such as upgrading their computers, to look as lean as possible.

We’ve been exploring some alternatives to the overhead ratio as part of our work as scholars of public administration and nonprofit management. Sure enough, we’re seeing evidence that there are other tools out there that work better when givers need to figure out which charities they think deserve their money.

A bigger bang out of more bucks

In our recent study, published in the Nonprofit Management & Leadership journal, we looked at a few alternatives to assessing how charities perform.

Data Envelopment Analysis is a mathematical program that can compare nonprofits with many different resources – like staff or volunteers – and outputs – like goods or services. DEA computes a performance score that has been used to compare public transportation agencies, nonprofit hospitals and social enterprises like international aid organizations.

The second approach is called Stochastic Frontier Analysis. This approach uses statistics to compare how well nonprofits with a similar mission produce or serve with the resources they have. SFA has also been used to compare service organizations, including hospitals, universities, and the fundraising efforts of nonprofit arts organizations. It has even been used to compare efforts to reduce energy consumption in American homes.

Both DEA and SFA have limitations, working better to evaluate nonprofits that produce something that’s easy to count – like packaged meals or affordable homes. These measurements are perhaps too complicated for the average small donor to consider, but organizations like Charity Navigator that assess nonprofits might use these tools to make their ratings more precise.

Habitat for Humanity, the world’s largest nonprofit homebuilder, shared data with our research team, including the number of homes built or rehabbed by nearly 792 of its affiliates across the U.S. Combining this information with publicly available details, we assessed how their overhead ratios compared with how many houses they built or rehabilitated in 2013.

Using these two methods that management scholars rely on, we found those affiliates that would otherwise rank low because of their higher overhead ratios, actually ranked very high using these alternatives.

For example, the highest-ranking affiliate according to the SFA analysis had a relatively high overhead ratio of 32 percent. Similarly, the top-ranking affiliate based on the DEA approach had an overhead ratio of 36 percent.

Yet these two groups built or rehabbed high numbers of houses relative to what they spent. In contrast, another affiliate with an overhead ratio of 2 percent did not deliver as many homes to low-income people relative to its outlays.

Nonprofits may want to consider our findings when they establish their strategies and work on their budgets. In addition, Charity Navigator, Candid and other groups that evaluate nonprofits could consider adjusting their standard metrics to include Stochastic Frontier Analysis, Data Envelopment Analysis or both.

We believe these alternative approaches we tried are better at assessing how good charities are at carrying out their missions. We think it will help everyone, especially the people served by organizations that exist to do good, if donors look more closely at what nonprofits achieve than what they spend.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Trauma patients recover faster when medical teams know each other well, new study finds

A new study from a Pittsburgh hospital finds that trauma patients recover faster when emergency medical…

When unpaid cooking, cleaning and child care get a dollar value, income inequality in the US shrinks

Women’s unpaid work at home has declined much more than men’s contributions have increased.

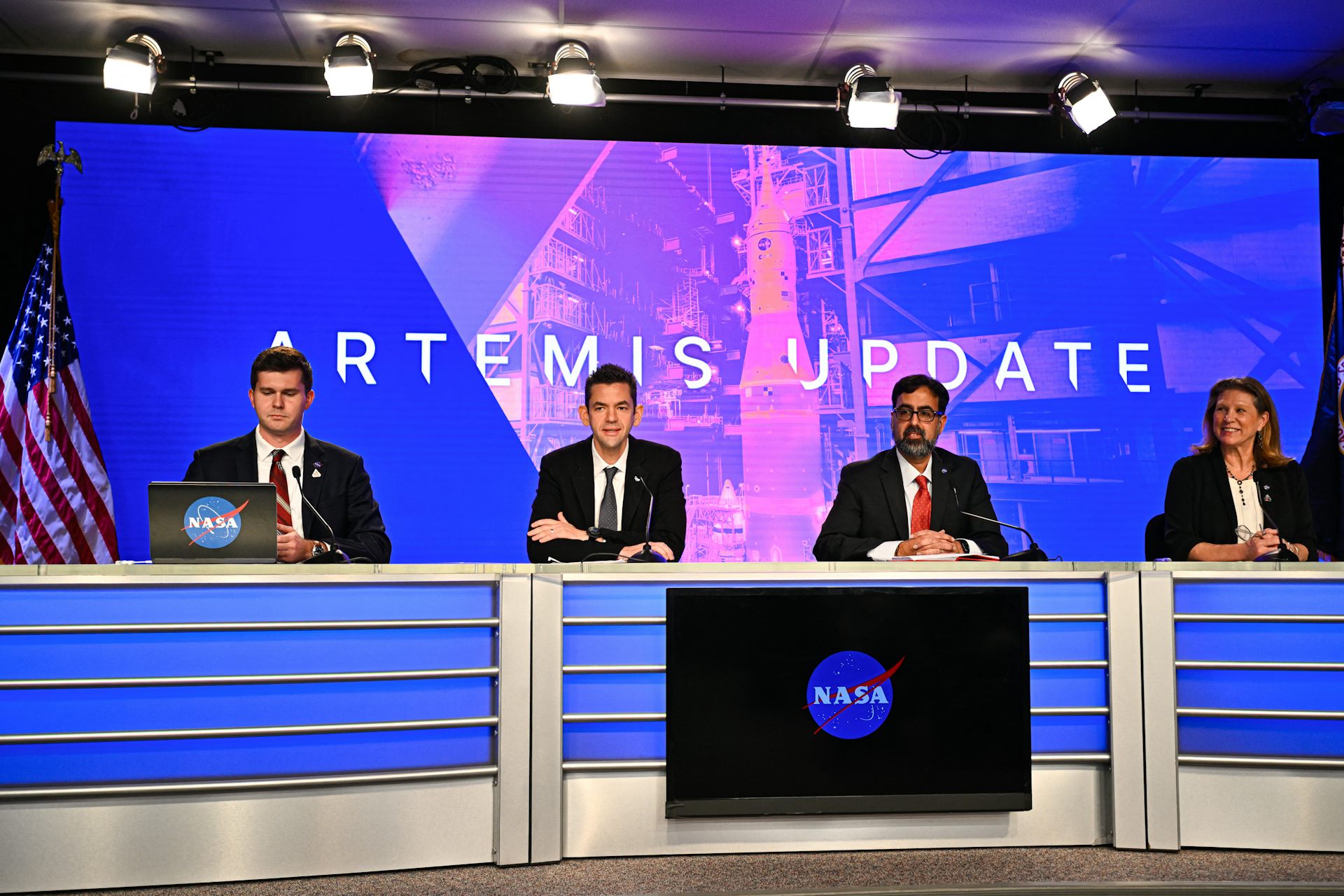

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…