Climate change resilience could save trillions in the long run - but finding billions now to pay for

As the expected costs of climate change grow, cities are on the frontlines of adapting to sea level rise and more intense storms – and finding ways to pay for it.

Is your city prepared for climate change?

The latest National Climate Assessment paints a grim future if U.S. cities and states don’t take serious action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The bottom line is that the costs of climate change could reach 10 percent of the entire U.S. economy by the end of the century – or more than US$2 trillion a year – much of it in damage to infrastructure and private property from more intense storms and flooding.

Cities can greatly reduce the damage and costs through adaptation measures such as building seawalls and reinforcing infrastructure. The problem is such projects are expensive, and finding ways to fund the cost of protecting cities against future and uncertain threats is a major financial and political challenge - especially in places where taxpayers have not yet experienced a disaster.

I’ve been part of a team that has been evaluating options for protecting Boston, one of America’s most vulnerable coastal cities. Our analysis offers a few lessons for other cities as they begin planning for tomorrow’s climate.

Investing in adaptation

A team of scientists from 13 federal agencies contributed to the fourth U.S. National Climate Assessment, which recently laid out the stark threats Americans face from sea level rise, more frequent and intense storms, extreme precipitation, and droughts and wildfires.

For example, the report notes that coastal zone counties account for nearly half of the nation’s population and economic activity, and that cumulative damage to property in those areas could reach $3.5 trillion by 2060.

The good news is that investing in adaptation can be highly cost effective. The National Climate Assessment estimates that such measures could significantly reduce the cumulative damage to coastal property to about $800 billion instead of $3.5 trillion.

The report does not, however, examine the complex problems of implementing these adaptation solutions.

The adaptation devil is in the details

The Sustainable Solutions Lab at the University of Massachusetts Boston has been closely involved with its host city and local business and civic leaders in devising such climate adaptation strategies and figuring out how best to implement them, including a study I led on financing investments in climate resilience. Our work identified a series of hurdles that make financing such projects difficult.

One key problem is that while public authorities – and taxpayers – will ultimately bear the cost burden of coastal protection, the benefits mostly accrue to private property owners. Higher property taxes or new “resilience fees” will be on the table – and unlikely to be politically popular.

Another problem is that resilience investments primarily prevent or reduce future damages and costs but don’t create much new value, unlike other public investments such as toll roads and bridges. For example, an investment in a sea wall might prevent property prices for coastal homes from falling or insurance premiums from rising, but it won’t generate any new cash flows to defray the costs for the city or homeowner.

Beware the big fix

In a separate study, we examined the feasibility of building a four-mile barrier across Boston Harbor with massive gates that would close if major storms threatened to flood the city.

We estimated that the project would cost at least $12 billion and could take 30 years to plan, design, finance and build. Ultimately we concluded it was unlikely to be cost effective and urged city officials to abandon the idea.

One key problem is the uncertainty regarding the extent and pace of sea-level rise, which is forecast to reach anywhere from 2 to 8 feet by the end of the century. But we really don’t know. By the time the barrier would become operational mid-century, we might realize that we didn’t need it – or worse, that it is woefully inadequate.

As sea levels rise, the gates, which would be the largest of their kind in the world and take many hours to open or close, would need to be activated more frequently and could potentially fail. In addition, the cost of such a barrier would be difficult to finance in an era of growing federal deficits and would choke off capital required for other more urgent adaptation projects.

In other words, it’s risky to put all our adaptation eggs in one very expensive basket.

The incremental solution

Instead, our group recommends that Boston and other cities pursue more incremental shoreline protection projects focused on the most vulnerable areas.

Examples include constructing seawalls and berms, elevating some roads and parks and creating incentives for property owners to protect their buildings. The key attraction of such an approach is that capital can be targeted in highly cost-effective ways to the most vulnerable areas that need protection in the short term. It also allows for more flexible planning as the science improves and climate impacts come into sharper focus.

Boston is already considering some projects like this that would cost around $2 billion to $2.5 billion over a decade or two. Coming up with that much money is still a big challenge, but it’s far more cost effective than the harbor barrier.

Another benefit is that this neighborhood-level approach would facilitate more local economic development and community participation. While making these areas more resilient, such investments would also involve upgrades in housing, transportation and other infrastructure.

This would go a long way toward ensuring that the community and taxpayers are on board when the discussion turns to costs.

Fair and equitable

Adapting to climate change will be a mammoth challenge for cities and citizens across the country – and world. Finding ways to finance adaptation in a fair and equitable way will be paramount to success.

Miami, for example, last year issued a voter-approved $400 million bond to pay for about half its planned resilience projects. In August – exactly a year after their region was devastated by Hurricane Harvey – most voters in Harris County, Texas, approved a $2.5 billion bond to pay for flood protection. And just last month, citizens in San Francisco approved a $425 million bond to pay a quarter of the costs of fortifying a sea wall.

One problem with these projects is the heavy reliance on bonds. We found that it would be better to spread the costs of protecting cities and towns across multiple levels of government and private sources of capital, and utilize a range of funding mechanisms, including property taxes, carbon-based fees, and district-level charges.

The hope is that voters and cities will approve such projects before disaster strikes – not after.

David L Levy is affiliated with the Sustainable Solutions Lab at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, which has received funding from the Barr Foundation.

Read These Next

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…

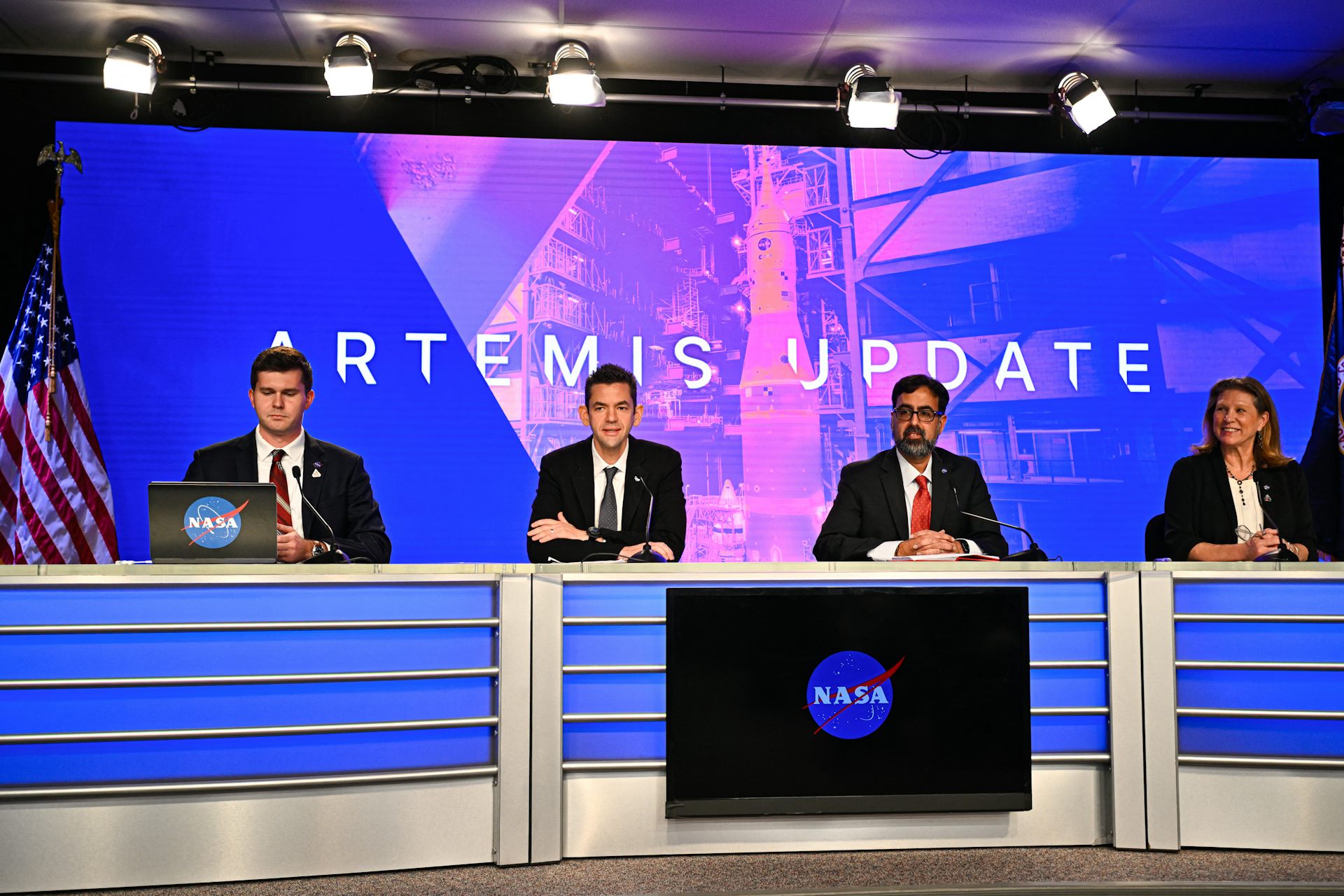

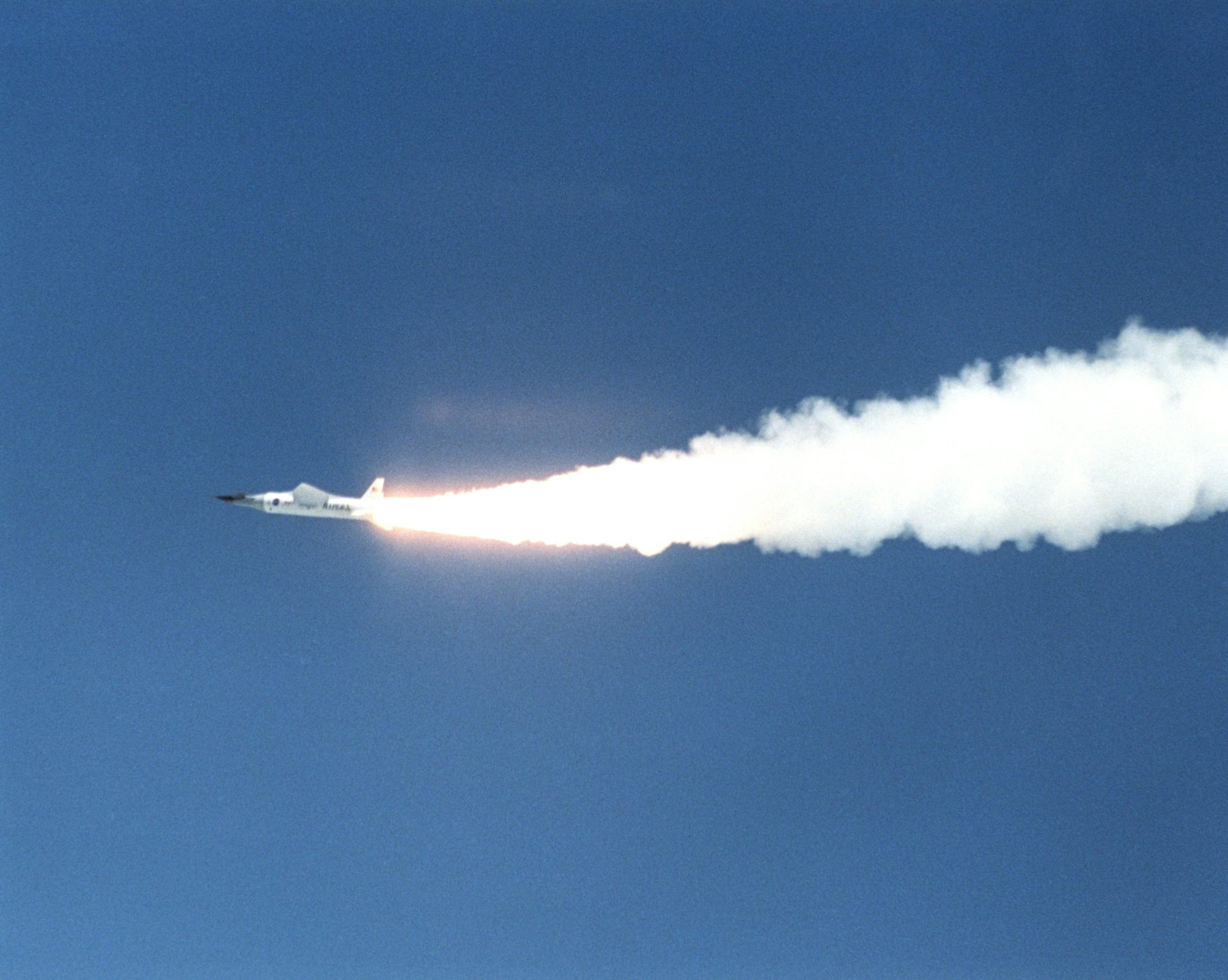

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…

AI and 3D printing help researchers create heat- and pressure-resistant materials for aerospace and

AI models are designing new metal alloys that have been 3D-printed and tested in the lab. The results…