Why politicians are the real winners in Amazon's HQ2 bidding war

Some say the more than 230 cities that lost their bids for Amazon's second headquarters were dupes in the retailer's game. In fact, they were willing participants with their own aims.

Now that Amazon has announced the winners of its competition to host its second headquarters, a question on many minds is whether it’ll be worth the incentives offered.

We have a different question: Why did so many cities play Amazon’s billion-dollar bidding game in the first place?

One media narrative has portrayed the leaders of losing locations as simply fooled by Amazon’s ingenious scheme. Most of the 238 cities that made bids – offering lucrative tax and other incentives – really didn’t have a shot because they didn’t fulfill the basic requirements, such as access to skilled human capital, sufficient infrastructure and population density.

According to this view, their role was to provide competition, driving down the tax bill Amazon would eventually pay in the locations it had already selected for its own business reasons. They also provided Amazon with valuable data about what types of incentives they would need to provide in the future as it expands.

There is certainly merit to this narrative. Where we disagree is the notion that the politicians were simple dupes in a game they didn’t fully understand. Rather, our research suggests it is far more likely they were willing participants.

A game of incentives

Amazon first unveiled its public competition for what has been dubbed “HQ2” last September.

The retailer gave interested city and state governments only two months to put together proposals for the opportunity to attract what Amazon described as a US$5 billion investment that would employ 50,000 workers.

Most states, and dozens of cities, jumped at the opportunity to put in proposals. Of the 238 initial bidders, Amazon culled this list down to 20 cities in January and requested additional information and the signing of non-disclosure agreements.

After reports began to leak that Amazon was splitting its investment between two sites, Amazon revealed that Long Island City in New York City’s Queens borough and an area in Northern Virginia known as Crystal City were the co-winners, each receiving half of the investment.

New York State reportedly offered $1.7 billion in incentives along with additional local tax reductions to lure Amazon to Long Island City, while Virginia and Arlington County put up a more modest $573 million. But both locations had something else in common: access to reserves of high-quality human capital and pre-existing hi-tech infrastructure. And according to urbanist Richard Florida, that’s what ultimately drove the decision in what some called a bait and switch.

Putting on a show

While this narrative is surely true, we believe something else is also going on here.

In our book, “Incentives to Pander,” we explain how offering incentives to companies is a way for cities that know they aren’t going to actually attract their investment to show voters just how hard they are trying, allowing them to minimize the blame when they don’t succeed.

To better understand the effects of offering investment incentives on voters, we asked 1,500 respondents of the annual YouGov survey about how a business investment that would create 1,000 jobs in their state would affect their support for the governor. Participants were randomly told one of the following:

- that the governor offered greater tax incentives than other states and won the investment

- that the governor offered greater tax incentives but didn’t win the investment

- that the governor offered tax incentives equal to or less than other states and won the investment

- that the governor offered tax incentives equal to or less than other states and didn’t win the investment.

Respondents were then asked whether they would be more or less likely to vote for the governor in the next election.

Unsurprisingly, respondents were always more likely to support the governor if the company invested in the state. What was striking was their response to the incentive.

A winning bid that included a bigger tax incentive led to a 5 percent boost in support relative to the scenario in which the governor won the investment but didn’t outbid other states. Even more interesting is that a losing bid that included a big incentive led to double the boost of support.

This study demonstrates the electoral value to politicians of making a splashy bid for an investment, particularly when they have good reason to believe their locality has little chance of actually winning it. We suspect that this allows a politician to avoid the potential blame of losing a bid as well.

So in terms of game theory, politicians have a dominant strategy to offer incentives to all prospective investors, whether a company needs a break or not or however improbable it is to actually happen.

Hide and seek

Amazon HQ2 is an extreme case of this thesis.

Mayors and governors offered up to $8.5 billion in incentives as a way to show effort. While some bids were serious, there was also rather embarrassing theater, such as the mayor of Kansas City publicly reviewing Amazon products during a video address to constituents, the city of Stonewall, Georgia, offering to rename the city after the retailer, and Atlanta proposing to build the company a train to deliver goods throughout the city.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo even jokingly offered to rename himself Amazon Cuomo if doing so would help win the bid.

What’s worse is that some mayors, governors and other city officials tried to hide the true costs of their bids from their constituents. Cities such as Dallas and Detroit avoided public disclosure requirements by not submitting bids though local government agencies. Instead, they expressed their interest through Chambers of Commerce, public-private economic development agencies and nongovernmental organizations that were formed only to pursue HQ2 and dissolved afterwards. Only now are they releasing the details of their failed bids.

Austin’s Chamber of Commerce immediately released a statement that they don’t intend to release details of its bid – ever.

And in other cases, such as Pittsburgh, normally transparent governments fought public records requests in the courts, at a minimum stalling the revelation of what was offered and possibly avoiding it all together.

Even many city council members were left in the dark.

In follow up experiments to our YouGov survey, when we told voters what the actual cost of the incentive would be to taxpayers, the vote bonus declined to zero. This is why transparency about the incentives is so important.

The real losers

This is the irony of HQ2.

Our research suggests elected officials will later try to use their efforts, win or lose, as a way to show that they are doing “all they can” for their communities and local economies. When asked for details about their actual effort, however, many will claim the Chamber of Commerce ate their homework.

The problem is simple: Elected officials are expected to create jobs in their communities, but most of the policies that facilitate economic development often take decades to pay dividends, such as investments in public education or providing adequate public services to small business.

There aren’t easy solutions but the first step is to recognize what is happening. Amazon HQ2 was another case of a company playing states and cities against each other to achieve special benefits. It’s also a story of complicit governments playing along with the game by offering grandstanding deals and keeping the details of the deals out of the public eye.

They both played a game – and their constituents are the real losers.

Nathan Jensen has received funding from the Center for Equitable Growth, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, and the Kauffman Foundation.

Edmund Malesky does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

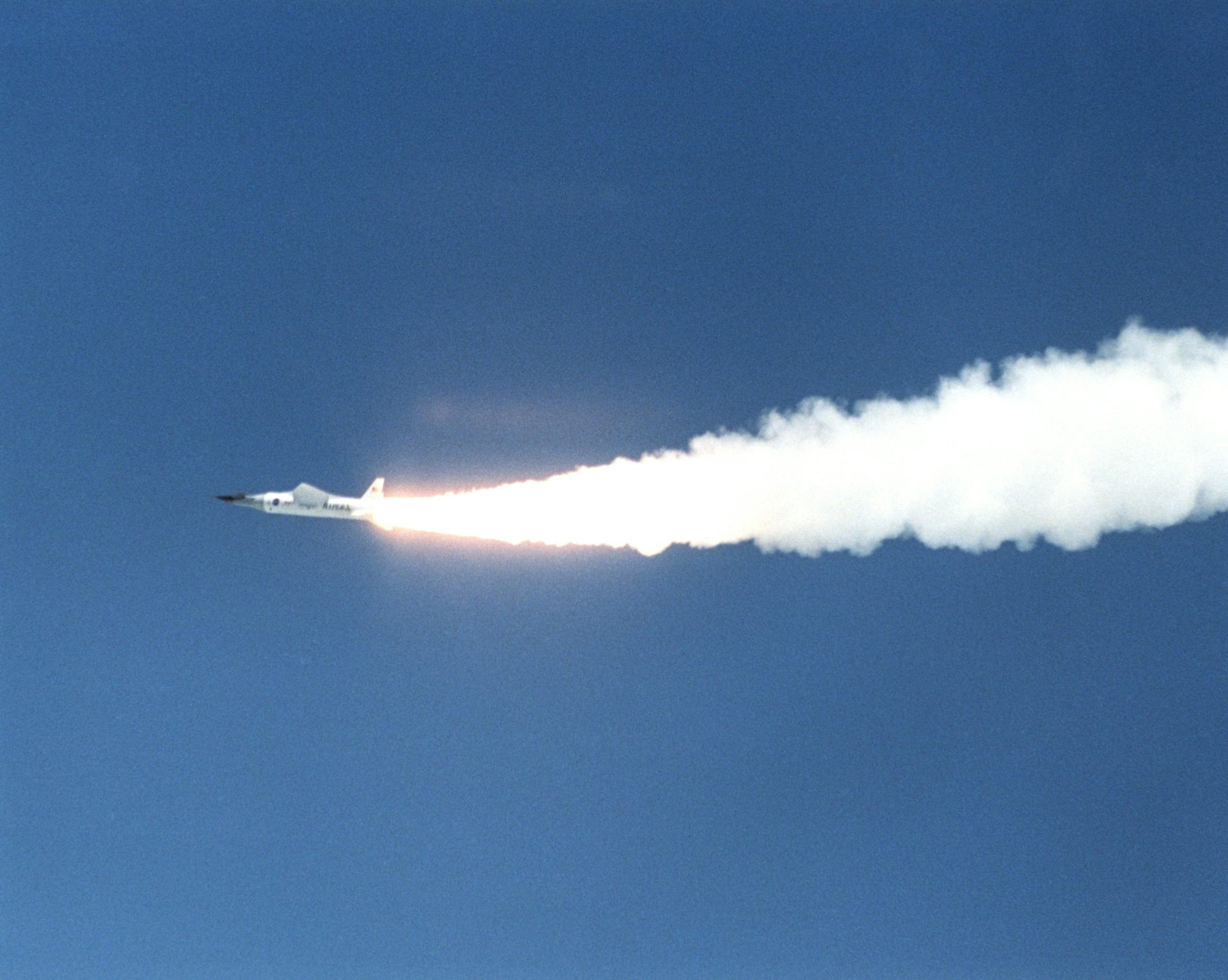

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…

AI and 3D printing help researchers create heat- and pressure-resistant materials for aerospace and

AI models are designing new metal alloys that have been 3D-printed and tested in the lab. The results…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…