Trump should wage a war on waste instead of battling the world over trade

Trump's plan to slap $200 billion more in tariffs on Chinese goods is premised on yesterday's waste-fueled economy. Tomorrow's economy is 'circular.'

President Donald Trump is fighting the wrong fight in his ongoing trade war with the rest of the world.

That’s because it’s premised on the old-school notion of the linear economy in which someone in another country, such as China, digs up raw materials and sends them to a factory, where they get turned into the finished product and shipped to the U.S. In exchange, money leaves the U.S. economy and flows to the countries where the product was made – creating the trade deficit Trump despises.

And here’s the important bit. Americans use the product for a while, throw it away, and it ends up in a dump. And then we buy another import.

The long-term effect? Our money goes to a foreign economy, and Americans end up with piles of garbage. Then we pay a foreign economy one more time to take the garbage off our hands. China is one country that used to take a lot of our garbage, but India, Pakistan and Nigeria are also big in this business.

A circular economy, by contrast, starts with the finished product, which can then be recycled domestically and reused, often at a fraction of the cost of manufacturing them new elsewhere. This keeps the money at home, which produces more domestic jobs and wealth.

As an researcher of corporate social responsibility, I’ve been exploring whether consumers are willing to buy more goods that have been remanufactured. My research suggests the answer is yes – if companies can figure how to produce more of them. And that’s where Trump and the federal government could play a big role.

Companies leading the charge

For now, companies and others in the American private sector are trying to lead the way, such as construction and mining equipment maker Caterpillar and automaker General Motors.

Caterpillar, for example, currently remanufactures 85 million tons of material a year, while GM has 142 manufacturing and other facilities that don’t produce any garbage by recycling, reusing or converting all waste to energy. GM also participates in a new online exchange that has about 1,000 partner companies buying and selling their recycled waste as raw material.

The nonprofit sector has also been playing a role, both in terms of research and practical efforts. Since 1991, the Center for Remanufacturing and Resource Recovery at my own Rochester Institute of Technology in upstate New York, for example, has been working with organizations such as the U.S. Marines Corps and Staples to take advantage of circular economy principles.

The center helped the Marines remanufacture detective drive shafts for light armored vehicles, which has saved the military force 78 percent versus the cost of buying them new. It also partnered with Staples to cut the use of non-recycled materials in office furniture by almost 90 percent while reducing the cost to the customer by over 40 percent.

Benefits of circular logic

The benefits can add up quickly.

General Motors, for example boasts revenue and savings of US$1 billion a year from its circular economy initiatives.

That’s just one company. Scaling up could yield over $1 trillion a year in savings globally – and that’s just in terms of mining and processing fewer raw materials. More broadly, were the European Union, for example, to replace all its imports with locally reused or recycled alternatives, it alone could generate $300 billion to $600 billion a year in savings, according to a 2012 report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a U.K. charity focused on promoting the transition to a circular economy.

Remanufacturing in the U.S. is already responsible for 180,000 jobs across sectors as diverse as aerospace, consumer products, office furniture and retreaded tires. Given how much the U.S. currently imports from abroad – and that remanufacturing is still less than 2 percent of total manufacturing in the U.S. – there’s room to create hundreds of thousands more jobs.

How Trump could help

While there are many ways the U.S. government could marshal its tremendous resources behind this effort, there are two in particular I think would pay dividends.

Both revolve around a core problem in remanufacturing: Most things we currently make can’t be remanufactured. That’s partly because of social barriers — customers may confuse remanufactured with used, which is a very different thing — and partly because they’re not made to be remanufactured.

Plastics in particular pose a significant problem to moving toward a circular economy. Globally, we only recycle or reuse about 9 percent of the plastic produced each year, with 79 percent going to landfills and 12 percent being burned.

Trump could support two ways to help solve this problem. Basically, with a carrot and a stick. The carrot involves setting a standard of design to ensure all products are made with future use in mind, as well as using his influence to encourage Americans to buy goods remanufactured in the U.S.

The stick is tax policy. Specifically, the government could tax products that can’t be converted into raw materials after they are used, as well as those that are made with less than a certain percentage of reused components – a minimum that would be set to gradually increase. Money raised through this tax could be used to support research into remanufacturing, community efforts to reach higher recycling and reuse targets, or other purposes.

Remanufacturing for the win

Some countries are already reducing their imports by going circular, putting the United States at risk of falling behind.

China, for one, has been systematically expanding its efforts in this area for over 20 years, while the EU is beginning to invest in a circular economy as well with a formal action plan, most recently revised in 2015.

In an entirely circular economy, the U.S. would most likely still import stuff from abroad, such as steel from China. But that steel would wind up being reused in American factories, employing tax-paying American workers to manufacture new goods.

In other words, the more circular Americans make their economy, the fewer products they’ll wind up importing and the more things that could bear the “Made in the USA” label.

Clyde Hull is a Professor of Management at the Saunders College of Business at RIT. He is also an associate faculty member of RIT’s Golisano Institute for Sustainabilty, which includes the Center for Remanufacturing and Resource Recovery. He is not involved in the Center’s operations.

Read These Next

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

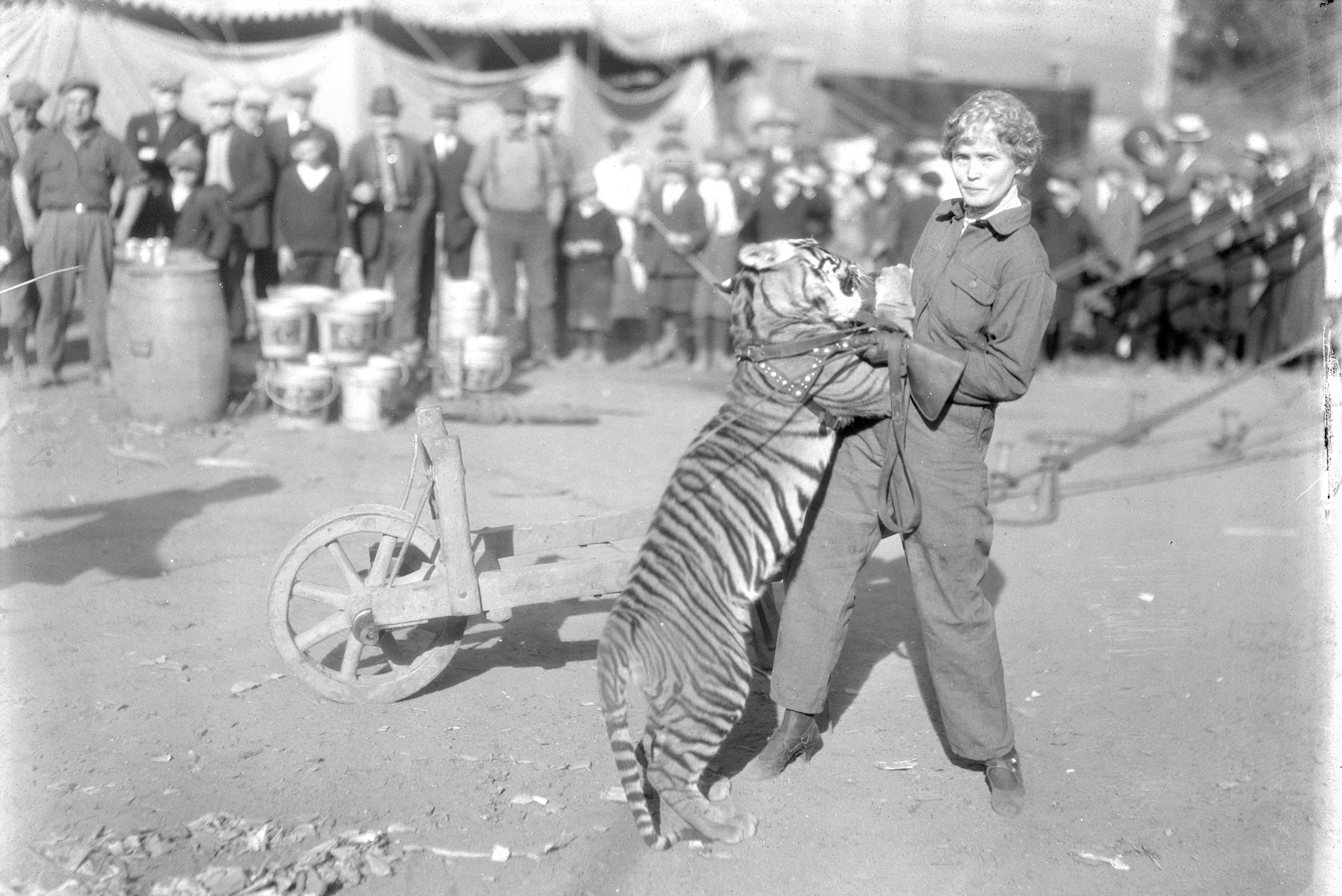

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.

A Plan B for space? On the risks of concentrating national space power in private hands

What does it mean for national security if access to Earth’s orbit depends largely on one company?