Why are there so many suckers? A neuropsychologist explains

Scam emails and phone calls are on the rise as it becomes ever easier to orchestrate fraud from anywhere in the world. New research sheds light on what makes some of us more susceptible than others.

If you have a mailbox, you probably get junk mail. If you have an email account, you probably get spam. If you have a phone, you probably get robocalls.

Unwanted messages and solicitations bombard us on a regular basis. Most of us hit ignore or delete or toss junk mail in the trash knowing that these messages and solicitations are most likely so-called mass-market scams. Others aren’t so lucky.

Scams cost individuals, organizations and governments trillions of dollars each year in estimated losses, and many victims endure depression and ill health. There is no other crime, in fact, that affects so many people from almost all ages, backgrounds and geographical locations.

But why do people fall prey to these scams? My colleagues and I set out to answer this question. Some of our findings are in line with other research, but others challenge common assumptions about fraud.

Scams on the rise

Sweepstakes, lottery and other mass-market scams have become surprisingly common in recent years.

The Better Business Bureau reported approximately 500,000 complaints related to just sweepstake and lottery scams over the past three years, with losses of almost US$350 million.

In the past, scams like these were perpetrated by relatively small local players and often done face to face, perhaps at an investment seminar for a bogus real estate opportunity.

Scams still happen the old-fashioned way, but today many more are being coordinated by transnational teams, including by groups in Jamaica, Costa Rica, Canada and Nigeria.

In recent years, fraud has grown into a pervasive global criminal activity as technology has lowered its cost while simultaneously making it easier than ever to reach millions of consumers instantly.

It is also much harder to catch and prosecute these criminals. For example, a robocall may appear on your caller ID as if it’s coming from your area code but in fact it’s originating in India.

Why people get taken for a ride

In order to study consumer susceptibility to mass-market scams, my co-authors and I reviewed 25 “successful” mass-market scam solicitations, obtained from the Los Angeles Postal Inspector’s office, in search for common themes.

For example, many of them included some type of familiar brand name, like Marriott or Costco, to increase their credibility and “authority.” Scammers frequently use persuasion techniques like pretending to be a legitimate business and using local area codes to foster familiarity. Or they make time-sensitive claims to increase motivation. Some of the letters we reviewed were quite colorful and included images of money or prizes and past “winners.” Others were much more businesslike and included legal-sounding text, to also create an aura of legitimacy.

We then crafted a prototype one-page solicitation letter that informed consumers they were “already a winner” and listed an “activation number” they would need to contact to claim their prize. We created four versions, which we assigned at random, intended to either manipulate authority (“We obtained your name from Target”) or pressure (“Act by June 30th”) to determine what persuasion factors motivated consumers more to respond.

The study was designed to replicate real scenarios – although participants knew they were part of an experiment – and examine factors that we suspected increased risk, such as comfort with math and numbers, loneliness and less income.

In our first experiment, we asked 211 participants to indicate their willingness to contact the activation number on the letter. They were then asked to rate the benefits and risks of responding to the letter on a 10-point scale and fill out a survey intended to identify their level of numeracy, social isolation, demographics and financial status.

We found that 48 percent of participants indicated some willingness to contact the number regardless of which type of letter they received. The consumers who indicated they would have responded to this solicitation tended to have fewer years of education and be younger. These participants also tended to rate the risks of contact as low and the benefits as high.

In a second experiment involving 291 individuals, we used the letters from the first one but added an activation fee to half of them. That is, some participants were informed that to “activate” their winnings they had to pay a $5 fee, while others were told it was $100. The rest saw no change from the previous experiment, and all other aspects of the design were identical except for a few additional survey questions related to participants’ financial situations.

We hypothesized that individuals who were willing to call and pay $100 would mean they’re especially vulnerable to this type of scam.

Even with the activation fee, 25 percent of our sample indicated some willingness to contact the number provided – including more than a fifth of those told it would cost $100.

Similar to the first experiment, individuals who rated the solicitation as having high benefits were more likely to signal intention to contact. We thought this experiment would help us identify some special vulnerable subtype, like the elderly, but instead, the interested consumers in both experiments were exactly the same – those who saw the potential for high benefits as outweighing the risks. There were no significant differences based on age, gender or other demographics we looked at.

Even though about 60 percent identified the solicitations as likely a scam, they also still viewed the opportunity as potentially beneficial. In some ways these advance fee scams may act as unofficial lotteries – a low cost of entry and a high chance of failure. While consumers are wary, they don’t completely write off the possibility of a big payoff, and some clearly are willing to undertake the risk.

Unfortunately, consumers overestimate their ability to back out if the offer turns out to be a scam. Once potential “suckers” are identified by responding to an actual solicitation over the phone call or by clicking on a fraudulent ad, they may be relentlessly targeted by phone, email and mail.

What to do about scams?

For many, solicitations via junk mail, spam email and robocalls are just incredibly annoying. But for some, they’re more than just a nuisance, they’re a trap.

To best protect yourself from being targeted, you need to be careful and use resources to help avoid scams. There are some services and apps intended to assist in screening calls and preventing identify theft. And some telephone companies such as T-Mobile allow you to opt in to such services. And more consumer education on the dangers of scams would help.

It is also important to resist clicking and responding to suspicious material in any way. Consumers who quickly identify a solicitation as a risk and dispose of it without wasting time are less vulnerable.

Given that the perception of benefits and risks were the most important factors in intention to comply, consumers should only focus on the risk and avoid getting sucked in by the potential benefits.

Stacey Wood receives funding from The California Foundation.

Read These Next

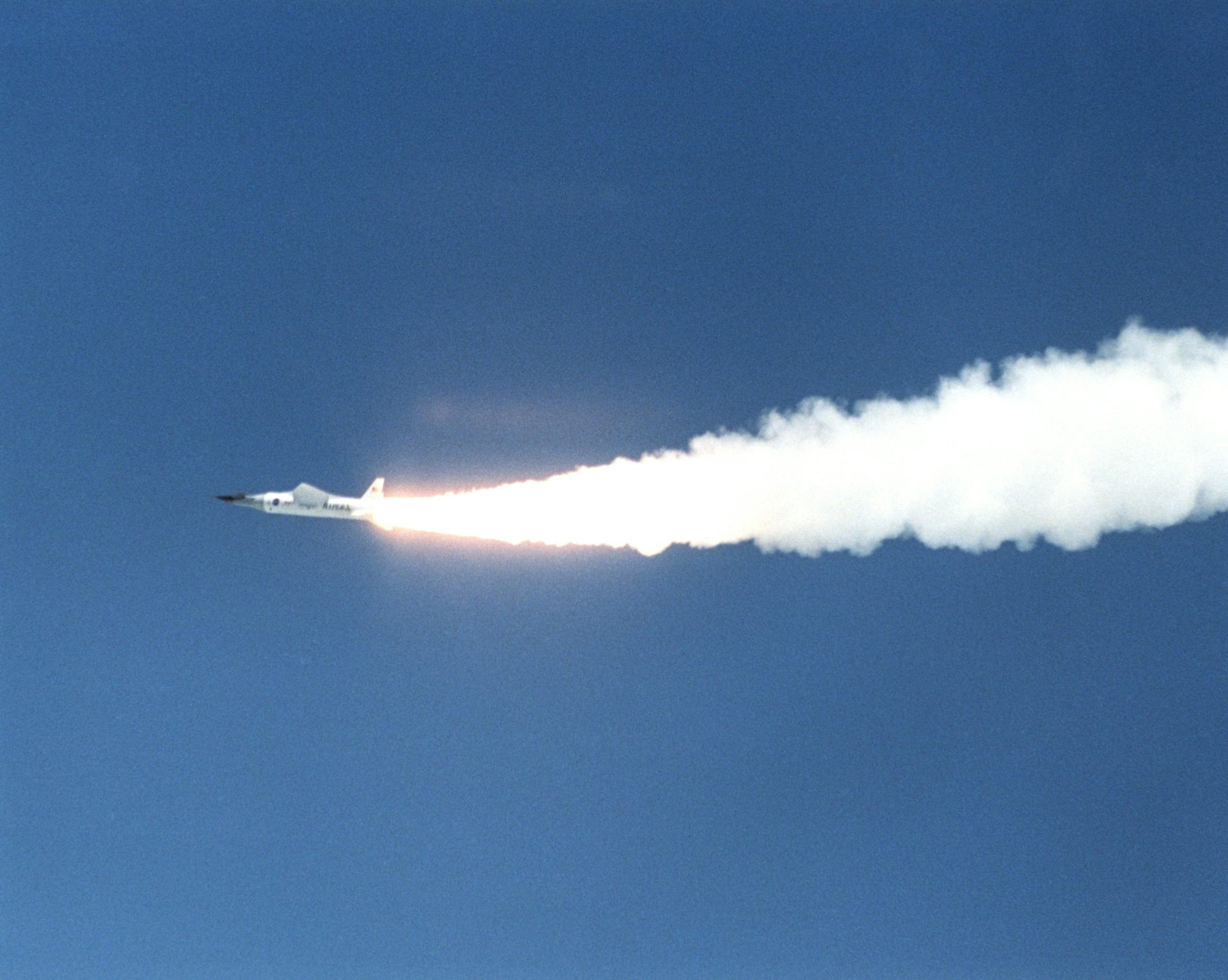

AI and 3D printing help researchers create heat- and pressure-resistant materials for aerospace and

AI models are designing new metal alloys that have been 3D-printed and tested in the lab. The results…

Why are so many statues naked? An art historian explains this tradition’s ancient roots

Nudity can express everything from innocence to sexual desire, from triumph to defeat.

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…