Mick Mulvaney turned the CFPB from a forceful consumer watchdog into a do-nothing government cog

The president recently nominated a new permanent director to take over the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. With the CFPB doing a fraction of the work it did under Obama, what kind of agency will she lead?

Until last Thanksgiving, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was known for forcefully pursuing its core mission, returning nearly US$12 billion to about 30 million consumers who had been taken advantage of by financial institutions.

But since then, the bureau has been known for … well, not much. After Obama-appointee Richard Cordray stepped down in November, President Donald Trump named as interim director, his budget chief Mick Mulvaney, who has long been a foe of the CFPB.

The president recently nominated a new permanent director – who has no consumer finance experience but is one of Mulvaney’s own deputies at the Office of Budget and Management – for a five-year term, with hearings likely to take place later this year.

So what does this mean for the only government agency focused on protecting consumers from financial shenanigans? I’ve been writing about consumer law for more than 30 years and follow the work of the CFPB closely. Let me explain what it used to do, what it’s doing now and what the change means for consumers.

The CFPB under Cordray

The CFPB was launched in 2011 in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The goal was to protect consumers from deceptive or misleading practices in the financial industry.

So what has the agency accomplished in its short life span? A lot. Here are a few highlights.

It fined Wells Fargo $100 million and forced it to refund fees it had fraudulently charged customers by opening millions of fake accounts without their permission. The bank was also required to hire an independent consultant to review its procedures. This probably wouldn’t have happened nationwide without the CFPB.

It blocked debt collector attorneys from suing consumers based on false information.

It discovered systemic problems with consumer credit reports and forced companies to correct errors.

It compelled credit card companies to refund illegal fees.

And the list goes on and on. In addition, after the bureau began publishing consumer complaints on its website, financial institutions have responded more than 700,000 times, often by providing remedies.

What the CFPB’s been up to lately

All that action came to a very sudden stop the day Mulvaney entered the building on Nov. 27. Although there was a brief tussle over who had the right to run the bureau, Mulvaney quickly took charge and installed his own people.

Since then, Mulvaney has brought only two cases, one of which was against Wells Fargo – the target of a Trump tweet – over the bank forcing consumers to pay for car insurance they didn’t need. That contrasts sharply with the work of Cordray, who, for example, filed nearly one case a week in 2015 and 2016.

Mulvaney has also sought to protect banks in other ways. After saying the bureau should be guided by the number of complaints it receives, Mulvaney raised the possibility of concealing those complaints from the public, which would lower the complaint database’s profile, and probably reduce the number of complaints it receives. The proposal, which is still under discussion, would also make it harder for consumers to obtain redress from misbehaving companies.

In June, Mulvaney fired the unpaid members of the bureau’s advisory committees, a move criticized by consumer advocates and financial industry figures alike. The advisory committees gave the bureau an opportunity to talk to consumer, financial and scholarly experts about how it should act.

Shifting justifications were offered for the firings in the subsequent days, from citing criticism of the committees to preventing leaks – all of which didn’t add up or weren’t backed by evidence. Mulvaney’s spokesperson even charged that the complaining committee members were more interested in protecting their taxpayer-funded trips to Washington than in protecting consumers, a charge that was belied by the fact that some members offered to pay their own way.

The next director

Many are wondering what will change once the president’s nomination to helm the bureau, Kathy Kraninger, is confirmed. We can’t be certain, because Kraninger has never spoken publicly about her views on consumer protection, but, given that she serves as Mulvaney’s deputy, I fear the answer is not much.

Many observers were surprised by the pick of Kraninger, who is not known to have any experience with the laws that the bureau enforces and interprets.

You might think that’s not a big deal. After all, how difficult can it be to master consumer law, which ought to be readily understandable by consumers?

But the truth is that consumer law is often terribly complex. I still learn new things about consumer law every week, and I’ve been teaching it for 30 years.

Kraininger’s supporters have noted that she acquired considerable managerial experience as an associate director at the Office of Management and Budget and deputy assistant secretary at the Department of Homeland Security. That may help her with management issues, but it’s hard to see how it will help her make decisions about which cases to bring or what protections consumers need.

To make the problem even worse, the CFPB’s jurisdiction is vast. The next director will have to work with laws governing credit cards, bank accounts, mortgages, student loans, car loans, debt collection, consumer leases, payday loans, credit reports, lending discrimination and much more. In short, the director’s work touches the life of nearly every American in multiple ways –which makes it important that the director know what she is doing.

Bureau critics complain that it is too powerful, making ignorance of the law even more troublesome. In fact, even a conservative commentator has said that Kraninger lacks the needed expertise, comparing her nomination with President George W. Bush’s ill-fated nomination of Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court in 2005.

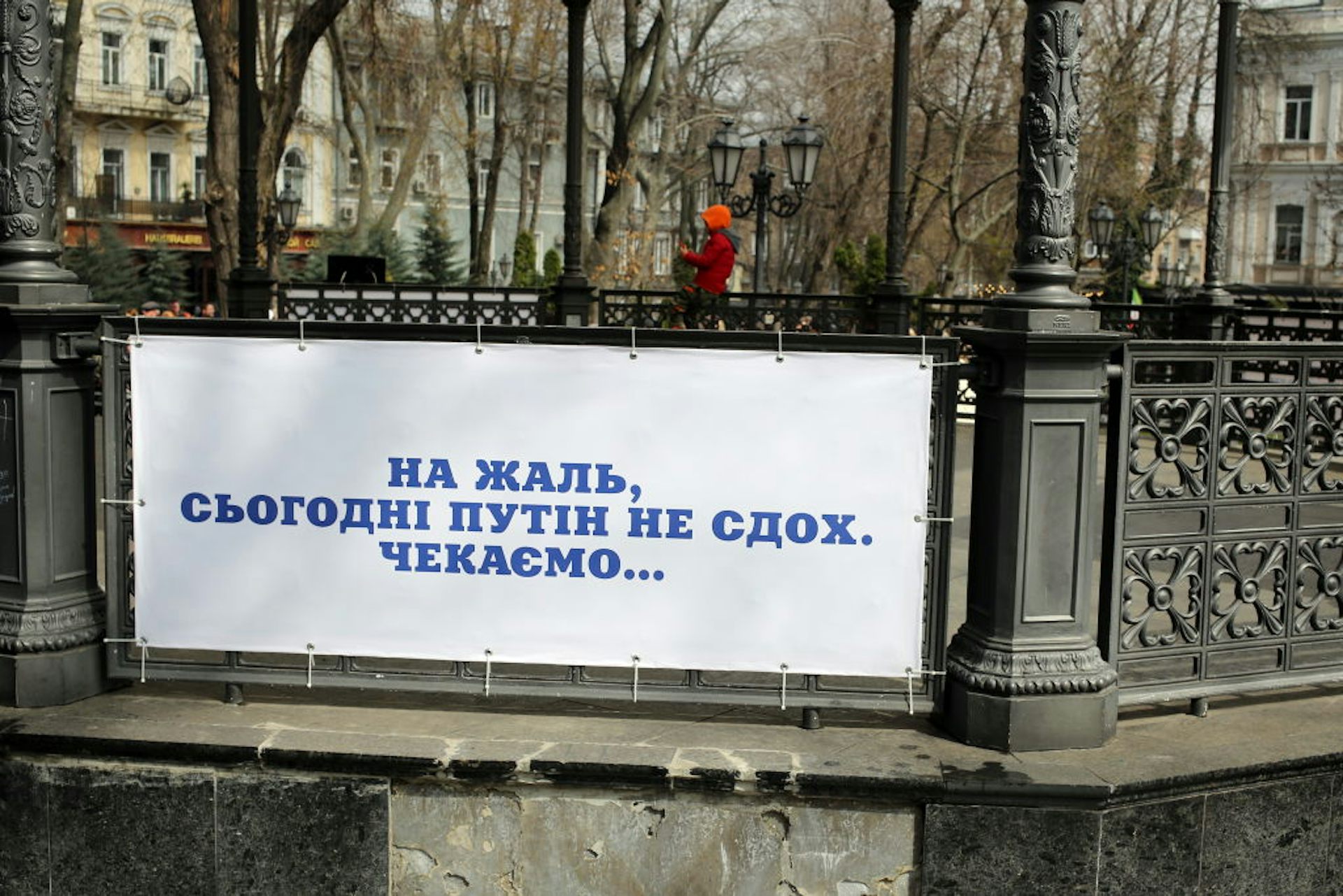

Casting a shadow

Meanwhile, Mulvaney continues to run the CFPB, which is facing new threats to its existence, particularly over whether its structure – intended to shield it from interference from the executive branch – is constitutional.

Early this year, a federal appeals court ruled that it was. In mid-June, a federal trial court in New York disagreed and called the CFPB’s design entirely unconstitutional.

While that court’s decision does not bind others, it casts a shadow over the CFPB and could encourage more lawsuits.

As for consumers, for now they will have to seek protection elsewhere than in this once-great consumer protection agency.

This article incorporates some material from a 2017 article written by the author along with Gina M. Calabrese and Ann L. Goldweber.

Jeff Sovern, together with three other then-employees of St. John's University, received a $29,510 grant from the American Association for Justice Robert L. Habush Endowment and a grant from the St. John’s University School of Law Hugh L. Carey Center for Dispute Resolution in 2014 to study arbitration. It resulted in an article. Along with Professor Kate Walton, he received a grant from the National Conference of Bankruptcy Judges Endowment for Education to study debt collection, resulting in another article. He is a member of the National Association of Consumer Advocates.

Read These Next

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…

When unpaid cooking, cleaning and child care get a dollar value, income inequality in the US shrinks

Women’s unpaid work at home has declined much more than men’s contributions have increased.