Who's to blame for keeping Time's #MeToo 'silence breakers' silent?

Time magazine named the #MeToo movement its 'person' of the year, highlighting the role companies and nondisclosure agreements play in keeping the victims of abuse silent.

Time magazine just named the #MeToo movement its “person” of the year, recognizing the women and men who raised their voices against abuses of power as the “silence breakers.”

For decades, victims of sexual harassment have remained silent about their experiences. The emergence of the #MeToo movement in the aftermath of the scandal surrounding movie mogul Harvey Weinstein raises larger questions about whether employers are partly to blame for their silence, particularly through the use of nondisclosure agreements.

Such contracts, written to keep details of business practices or a settlement confidential, are now in the sights of lawmakers. Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and Washington are all considering bills that would declare such provisions unenforceable.

Are confidentiality clauses to blame for all those years of silence? And will legal changes offer victims more freedom in deciding whether to speak out?

Confidentiality agreements vs. settlements

Media accounts tend to refer to “nondisclosure” agreements as a generic label for any contract that requires someone to keep a secret.

But when I worked as an employment lawyer, we dealt with two different types of agreements containing nondisclosure provisions: standard confidentiality agreements (intended to protect an employer’s business secrets) and settlement agreements (intended to resolve a lawsuit or the threat of one).

Standard confidentiality agreements are quite common. Employers typically ask employees to sign them at the start of employment to protect the company’s research and development, trade secrets and other nonpublic information.

The problem is that an employee without legal training might reasonably believe that these agreements are more restrictive than they actually are.

A lawyer reading a standard confidentiality agreement would look at the items listed in the definition of “confidential information.” Even though the definition is usually quite long, a lawyer would take note of the words that the definition doesn’t contain. Odds are, the definition doesn’t limit an employee’s right to disclose illegal acts, including harassment.

Employers don’t place limits on disclosing illegal conduct because they know they probably wouldn’t hold up in court.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act protects an employee’s right to “oppose” harassment and other forms of discrimination in the workplace, and there is some case law supporting the idea that public opposition to harassment such as writing letters or picketing are protected.

In addition, the National Labor Relations Act protects a worker’s right to engage in “concerted activity” – “acting together to improve wages or working conditions” – which arguably includes discussions on social media about a workplace rife with harassment.

Here’s the problem. Average employees don’t read a contract like a lawyer. They also wouldn’t necessarily know about built-in protections under Title VII or the National Labor Relations Act, or that they apply regardless of what the contract says.

An employee victimized by workplace harassment or abuse might take one look at a lengthy contract labeled “Confidentiality Agreement,” with tons of verbiage around confidentiality, and decide not to speak out. The rare employee who went public in the past might have done so in fear of having breached their contract.

In this sense, new legislation around these issues could be helpful. By clarifying that these agreements don’t cover disclosures of harassment, it sends a message to employees that they are free to speak out. Legislative efforts may also force employers to be more transparent in their contracts about an employee’s right to speak.

Settlement agreements are different

Settlement agreements are a lot less common. And they are treated quite differently under the law.

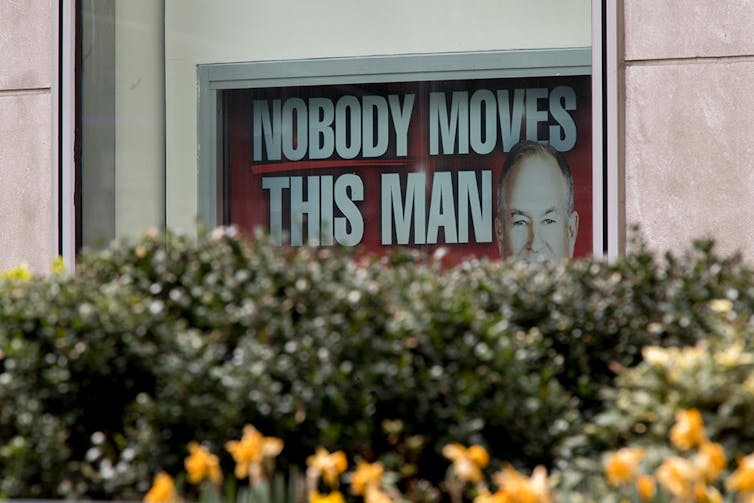

Settlement agreements tend to come about when an employee is leaving a job, and the employer is paying him or her in exchange for waiving legal claims. They often arise if an employee has threatened to bring a lawsuit or actually filed one against the company. For example, former Fox News host O'Reilly reportedly secretly settled a sexual harassment claim by a network contributor for US$32 million.

These agreements can have a number of provisions intended to keep the victim (as well as the company) from speaking publicly. They might require parties to the agreement to keep the amount of the settlement secret. Or prohibit the parties from saying anything disparaging about the other. These “nondisparagement” provisions can be narrow, prohibiting only defamation or slander. They can also be quite broad, prohibiting any statements that would adversely affect the other’s reputation.

Courts do not hesitate to enforce these contracts, even when they have the effect of preventing employees from speaking publicly about what happened to them. Employees are often represented by lawyers, and courts view these restrictions as part of a bargained-for exchange to keep the peace.

The legislative dilemma

Legislation that targets the enforceability of settlements with secrecy clauses will mean a change to existing law. And it presents difficult policy questions.

Reporters have documented a trail of settlement agreements involving Weinstein, through which he managed to obscure years of apparent misconduct. One such agreement apparently even required a victim to say “positive things” if the press ever inquired about Weinstein.

At the same time, such provisions can also protect victims from retaliatory statements to the public or to subsequent employers. Another O'Reilly accuser recently filed suit for defamation and breach of the nondisparagement provision of a settlement agreement after he characterized her original complaint as a smear campaign.

When it comes to settlement agreements, legislators should attempt a balanced approach, identifying exceptions for their legitimate use and prohibiting those whose purpose serves to obscure misconduct. Narrow nondisparagement clauses – which prohibit only defamation, slander or libel – should be permissible if they protect both parties from false statements by the other.

Ultimately, state legislatures are advancing the conversation by taking on this issue. Doing so also forces employers to think harder about why they demand secrecy in the first place.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Nov. 21, 2017.

Elizabeth C. Tippett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Hezbollah − degraded, weakened but not yet disarmed − destabilizes Lebanon once again

Hezbollah’s entry into the current war followed the killing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The group has…

When unpaid cooking, cleaning and child care get a dollar value, income inequality in the US shrinks

Women’s unpaid work at home has declined much more than men’s contributions have increased.

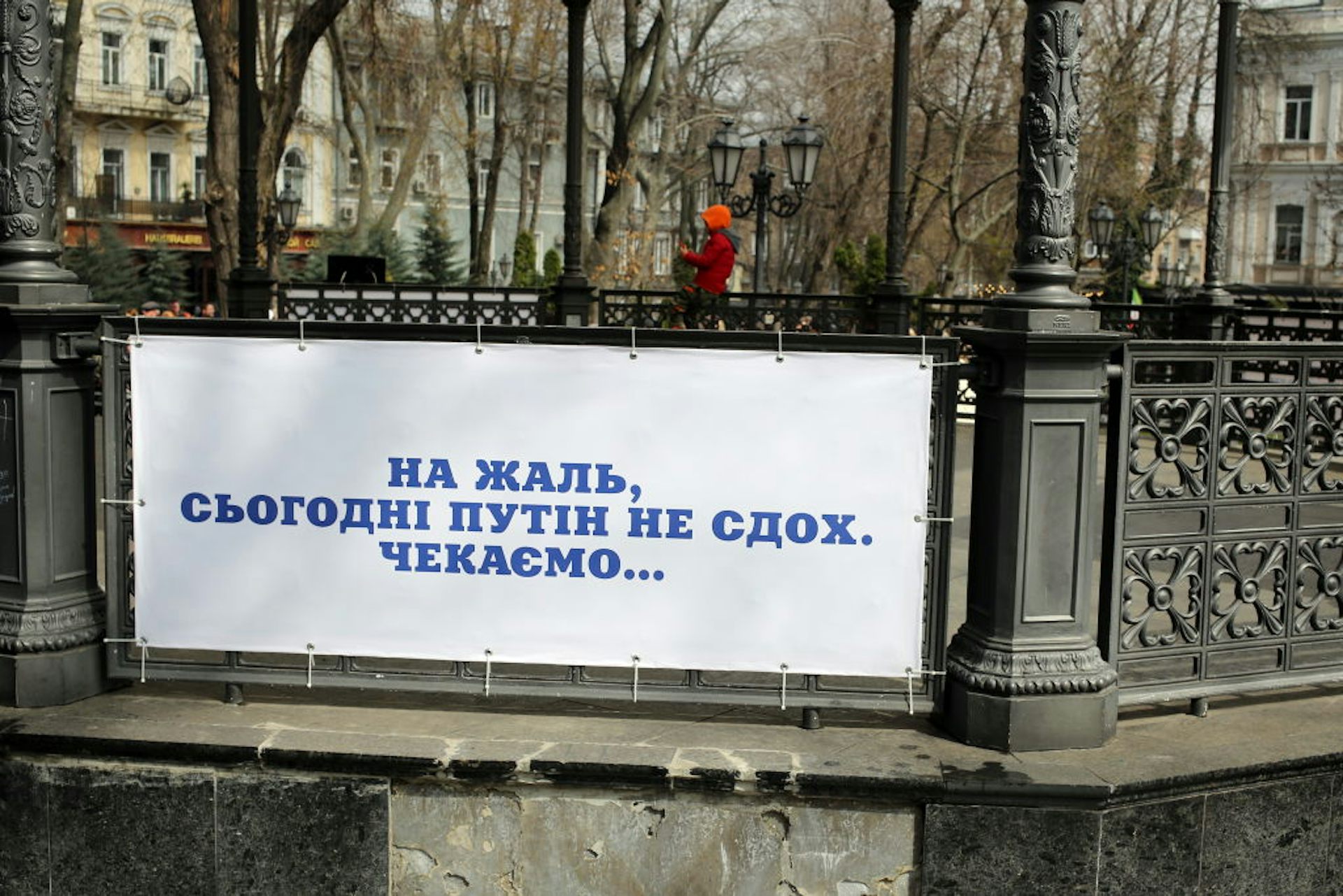

Front lines of humor: Dark humor voices Ukrainians’ hopes for victory

Humor has served many functions since Russia’s full-scale invasion, from providing Ukrainians with…