How the tax package could sap the flow of charitable giving

More than US$20 billion per year in giving is potentially at stake.

The tax bills currently making their way through Congress could end up making Americans less charitable.

The bills that recently cleared the House and the Senate, which need to be reconciled, would have different consequences for charitable giving. But both would raise the price of donating for millions of Americans, thereby reducing how much the nation gives to charity overall.

The precise impact of this tax code overhaul, however, would depend on which provisions wind up on the books.

As an economist and a scholar of philanthropy who researches how public policies shape charitable giving, I have been following the pending tax proposals closely and examining their potential impact. My research suggests that the proposed changes could lead Americans and U.S. companies to donate roughly US$20 billion less per year to charity.

Standard deduction and tax rates

One of the primary ways giving could be reduced is through two of the tax plan’s key features – significantly boosting the standard deduction and cutting the top marginal tax rate.

Research I co-led showed that such changes, based on an earlier version of the tax plan, would reduce household charitable giving by $13.1 billion per year. That would mark a 4.6 percent decline from the $282 billion American households gave in 2016.

We also determined that the share of households that itemize their tax returns would fall to approximately 5 percent from the current 30 percent.

While we based our estimates on a reduction in the top rate from 39.6 percent to 35 percent and a 75 percent increase in the standard deduction, the current House and Senate bills differ slightly from that baseline and each other, both in terms of top marginal tax rates and where they kick in for different income levels. For example, both bills would increase the standard deduction by 90.5 percent.

These ongoing differences make it hard to discern what the precise differences would be. But if the changes in the latest versions become codified, the share of filers who get a tax break – a built-in incentive – for their charitable gifts would fall even further than my team had estimated.

In short, I now anticipate the loss to charitable giving from the tax code changes to top our estimate of $13.1 billion.

Estate tax

Both bills would also reduce the incentive to give after a wealthy taxpayer dies.

The estate tax encourages giving with a dollar-for-dollar deduction from estate and gift tax liabilities matching any amount of money bequeathed to charities after death. In other words, if you owe a tax of $5 million on your estate, you could give $100,000 to charity and lower your IRS bill to $4.9 million.

The number of families this actually applies to is tiny, after growing smaller in recent years. Only one in 500 estates belonging to the people who die in any given year owe anything, after Congress sharply increased the threshold under which estates are exempt from the tax. And rich families rely on loopholes to get out of it or reduce the tax’s impact.

Currently, estates under $5.5 million are exempt for taxpayers filing as individuals and estates twice that size for couples.

The Senate bill calls for doubling current exemption levels to $11 million for an individual and $22 million for couples. The House plan would double exemption levels and then end the estate tax altogether in 2024.

Estimates regarding the effects of repeal range widely. However, there is complete consensus that doing away with this levy would reduce charitable bequests and donations wealthy Americans make during their lifetimes.

Based on my analysis, I anticipate that doing away with the estate tax altogether would cut giving by approximately $7 billion per year.

Levying it on the extremely small share of the very wealthiest households would surely reduce how much money is left to charities from current levels. But it is hard to extrapolate the approximate impact of this change because no researchers have modeled estimates with these levels of exemptions and tax rates.

Corporate giving

Companies and corporate foundations donated $18.6 billion in both cash and in-kind goods and services to U.S. charities in 2016, according to the Giving USA report, which the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy researches and writes in partnership with the Giving USA Foundation.

My colleagues and I have not yet thoroughly studied how the pending reductions in corporate marginal tax rates might affect how much money businesses give to charity. But our models do show that the proposed reductions in the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent would reduce the incentives for corporations to give.

Businesses give for many reasons. However, it is reasonable to expect that dramatically cutting the top corporate tax rate would reduce corporate donations by an estimated $1.4 billion – a 7.6 decline from the amount business gave in 2016.

Johnson Amendment

The House bill includes a provision that would leave churches and other nonprofits, which by law must be nonpartisan, far more free to engage in political speech than they are today.

Nonprofit leaders warn that this measure, left out of the Senate version, could have major consequences.

Watering down this restriction – known as the Johnson Amendment – is wildly unpopular with the vast majority of American voters, according to surveys. I suspect that it would be even less popular if more people understood the potential effects of this change on charities.

If churches and all other charities were to become largely able to endorse and support political candidates and retain their tax-exempt status, as the House’s tax bill would do, it would suddenly change the longstanding differences between giving to charities instead of explicitly political organizations and lobbying groups.

Currently, taxpayers may deduct their gifts to charities but not the money they donate to lobbying outfits and political parties.

If donations that are essentially political became tax-deductible, some donors would be likely to reallocate donations to charities, including new supposedly charitable entities created expressly to raise money to lobby for political causes.

Following such rejiggering, the consequences of this shift would reduce federal revenue by an estimated $2.1 billion over 10 years, the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation calculates.

While this change might create the appearance of an increase in charitable giving, it would be misleading to see the reallocation of giving from political parties and causes to politically charged charities as an authentic improvement for the charitable sector as a whole.

Dynamic scoring

Economic growth, of course, is good for philanthropy.

People tend to give less to charity during economic recessions and give more when times are better. After adjusting for differences in inflation, total giving fell an average of 0.5 percent annually during years when the U.S. economy was in recession since 1957.

On the flip side, the sum total of donations grew an average of 4.5 percent per year during boom times, according to Giving USA data.

For multiple reasons, most research regarding the effects of tax policy on philanthropy does not use “dynamic scoring,” however. That is, it does not account for the potential economic growth effects tax policies are expected to have (or not) on growth.

Universal charitable tax deduction

So what could lawmakers do if they wanted to avert this outcome?

The most straightforward way to prevent the tax code overhaul from reducing charitable giving would be to let all taxpayers deduct donations from their taxable income.

My team and I have modeled the effects of this approach, which many nonprofit leaders are urging Congress to adopt.

New bills that would do that are pending in both the House and the Senate. Both would create a universal deduction for non-itemizers, and both of them would cap this tax break at gifts equal to one-third of the standard deduction.

While the proposed caps would offer no incentive to give above the limit, and, therefore, it would be better without caps, those thresholds are high enough that they are unlikely to affect many otherwise ineligible taxpayers’ giving patterns.

So far, however, provisions along these lines are not on the table as part of the broader package.

Patrick Rooney and the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy have received millions of dollars of grants to fund research that benefits the philanthropic sector generally and many charities specifically. Rooney has consulted with and been affiliated with the advisory committees and legal boards for numerous charities and foundations over the years. None have funded this essay or have provided feedback on it in advance of its release.

Read These Next

GLP-1 drugs may fight addiction across every major substance, according to a study of 600,000 people

GLP-1 drugs are the first medication to show promise for treating addiction to a wide range of substances.

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

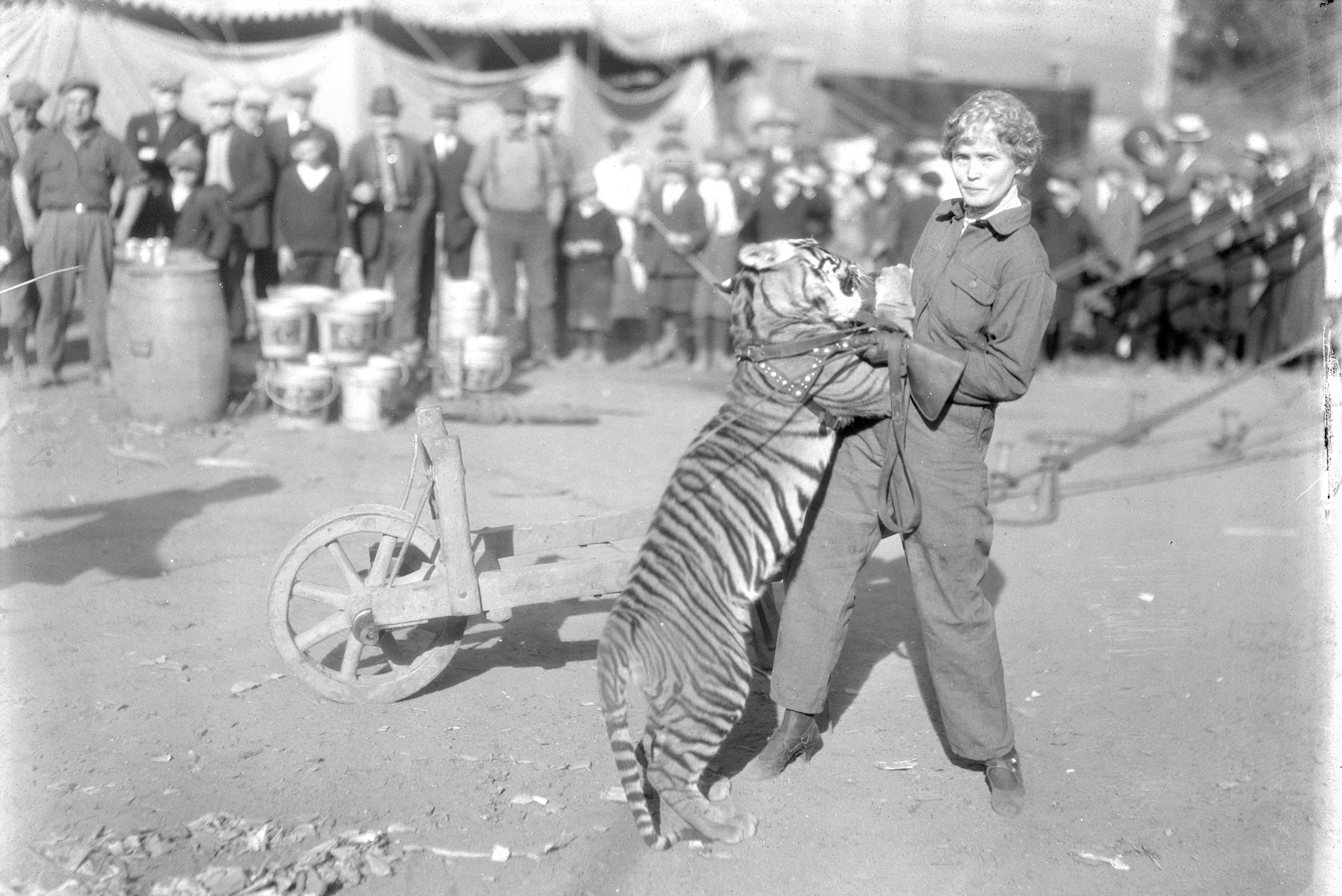

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.