Why does the price of turkeys fall just before Thanksgiving?

An economist explains why turkeys defy the economic laws of supply and demand.

Thanksgiving is a great U.S. holiday during which people consume huge quantities of turkey, stuffing, cranberry sauce and pie.

One of the stranger things about this holiday, however, is that a few days before everyone starts cooking, whole turkeys are suddenly discounted by supermarkets and grocery stores.

And this happens every holiday season: The price falls just before Thanksgiving and stays low until Christmas. For example, in the average year, November’s price per pound for turkey is about 10 percent lower than the price in September.

Why does the price come down at the one time of the year when demand for the product spikes the most – before a holiday that’s literally dubbed “Turkey Day”?

The turkey demand curve

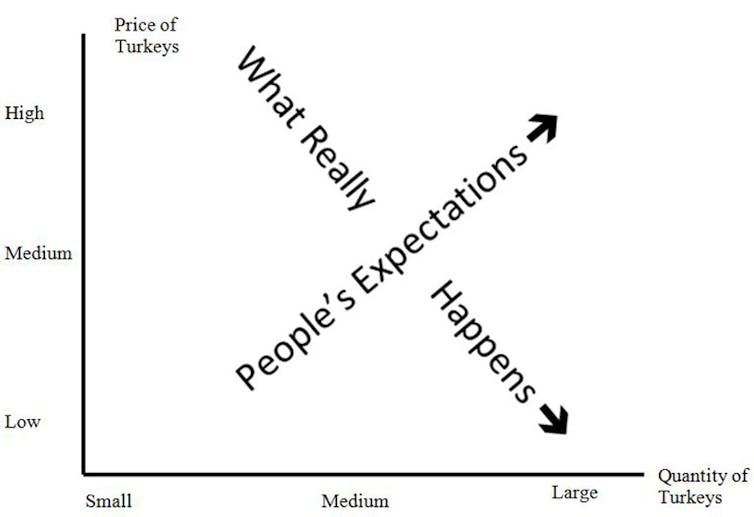

Most people expect turkey prices to rise because many more people are buying the birds. My family is an example of this buying phenomenon, since we almost never eat turkey except at Thanksgiving.

In general, when there is a fixed quantity of something to sell and demand for the product spikes, prices rise. This is why a dozen long-stem red roses typically cost a lot more on Valentine’s Day than at other times of the year.

In more formal economic language, the demand curve for turkeys shifts outward at Thanksgiving, which means people at this time of year are interested in buying more of these birds regardless of the price. Even the most casual shopper in food stores this week can observe this increase or shift in demand as more people are buying turkeys to cook.

However, each Thanksgiving the price of turkeys doesn’t rise. Instead, it falls during the holiday period as many stores advertise special low turkey prices, and over time turkey prices have generally fallen.

Not only do supermarkets that sell turkeys year-round make the bird a featured item, but some food stores and warehouse stores that don’t typically sell whole turkeys offer them for a limited period of time to customers. This means not only does demand for turkeys increase, but the supply of turkey increases too. This boost in supply drives prices downward.

Food stores are not upset that the price of turkey falls at this time of the year because they are interested in maximizing profits – not in maximizing the revenue they get from selling each bird.

Turkeys are not very profitable items, even at full price. The wholesale price of a whole frozen turkey in 2016 was US$1.17 per pound, while the average retail price was $1.55. This means at full price stores made less than 40 cents per pound. To give you a comparison, the USDA reports the difference between the wholesale and retail price in 2016 was $2.79 per pound for beef and $2.25 per pound for pork.

Stores, however, know that people coming in to buy turkeys are likely to purchase other items, too, such as seasonings, disposable roasting pans and soda. The other items are where stores make their money, since the profit margins on these items are much higher than on frozen turkeys.

Why does the turkey supply skyrocket?

Because of the desire to attract people to stores, the supply of turkeys needs to skyrocket just before the holiday so that freezer cases overflow with the birds.

How does this dramatic increase in supply happen? It occurs because turkeys are slaughtered continuously throughout the year and then put into cold storage.

The Department of Agriculture has tracked the amount of turkey in wholesale freezers for the past century. The past few years of data show turkey stocks slowly build up each year until they reach a peak in September, when the U.S. has over half a billion pounds on reserve. Between September and December, turkey stocks plummet as stores purchase over 300 million pounds’ worth and put them on sale. Then farmers, processors and wholesalers slowly rebuild their stocks for the next year’s holiday season.

The 500 to 600 million pounds of turkey in cold storage by the end of each summer means there are almost two pounds of turkey for every man, woman and child in the U.S. waiting to be released each holiday season. That figure doesn’t include live turkeys, which some people prefer, and also doesn’t take into account vegetarians (about 3 percent of the population), newborns who are not eating solid food (about 1 percent) and people like my brother-in-law and me who don’t like eating turkey at any time of the year.

What does this mean for the typical consumer?

The National Turkey Federation, the organization whose goal is to get the country to eat more turkey, estimates that 88 percent of Americans will eat turkey on Thanksgiving. If buying turkey is on your holiday or regular shopping list, then from now to Christmas it is the time to stock up, when prices are cheap. Otherwise, eating turkey at other times of the year means your wallet will get plucked for more money.

For those of you eating turkey during this holiday, enjoy. My brother-in-law and I will be happily ensconced at the end of the table feasting on lamb and, while not eating turkey, appreciating and giving thanks for a day to be with friends and family.

Jay L. Zagorsky does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Hezbollah − degraded, weakened but not yet disarmed − destabilizes Lebanon once again

Hezbollah’s entry into the current war followed the killing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The group has…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

‘Destruction is not the same as political success’: US bombing of Iran shows little evidence of endg

As US bombing operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya have shown, destruction is not the same as political…