How Lincoln's embrace of embalming birthed the American funeral industry

Dying in America 200 years ago was a simply family affair, devoid of pomp. The US Civil War and Abraham Lincoln's embrace of embalming changed everything.

If you died 200 years ago in America, your family would wash and dress your body and place it in a bed surrounded by candles to dampen the smell of decomposition.

Your immediate family and friends would visit your house over the course of the next week, few needing to travel very far, paying their respects at your bedside. Before the body’s putrefaction advanced too far, the local carpenter would make a simple pine casket, and everyone would gather at the cemetery (or your own backyard, if you were a landowner) for a few words before returning you to the earth.

You would be interred without any preservative chemicals, without being cosmetized with touch-ups like skin dyes, mouth formers or eye caps. No headstone, flowers or any of the other items we relate to a modern funeral. In essence, your demise would be respectful but without pomp.

Things have changed pretty substantially since America’s early days as funeral rites have moved out of the house and into the funeral home. How did we get here and how do American traditions compare with typical practices in other countries?

In doing research for “Memory Picture,” an interactive website I’m building that explains the pros and cons of our interment options, I’ve discovered many intriguing details about how we memorialize death. One of the most fascinating is how the founding of the modern funeral industry can essentially be traced back to President Abraham Lincoln and his embrace of embalming.

Embalming’s beginning

The simple home funeral described above was the standard since the founding of the Republic, but the U.S. Civil War upended this tradition.

During the war, most bodies were left where they fell, decomposing in fields and trenches all over the South, or rolled into mass graves. Some wealthy northern families were willing to pay to have the bodies of deceased soldiers returned to them. But before the invention of refrigeration, this often became a mess, as the heat and humidity would cause the body to decompose in a matter of a couple of days.

Updating an ancient preservation technique to solve this problem led to a seismic change in how we mourn the dead in America. Ancient Egyptian embalmings removed all internal organs and blood, leaving the body cavity to be filled with natural materials.

In 1838, the Frenchman Jean Gannal published “Histoire des Embaumements,” describing a process that kept the body more or less intact but replaced the body’s blood with a preservative – a technique now known as “arterial embalming.” The book was translated into English in 1840 and quickly became popular in America.

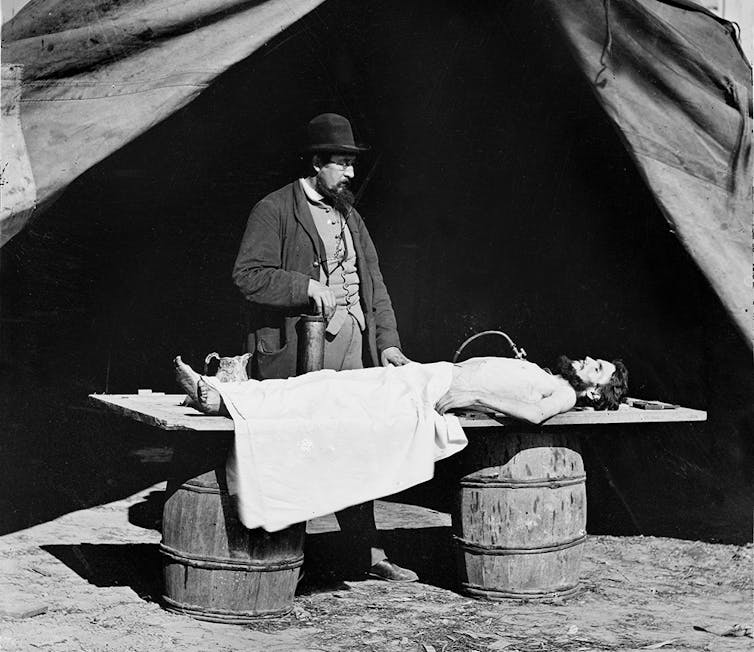

Catching wind of these medical advances, opportunistic Americans began performing rudimentary embalmings on the corpses of northern soldiers to preserve them for the train ride home. The most common technique involved replacing the body’s blood with arsenic and mercury (embalming eventually evolved to using variants of formaldehyde, which is still considered a carcinogen).

Results improved, but not on a grand scale. These were “field embalmings,” performed by nonprofessionals in makeshift tents set up next to the battlefield. Results were unpredictable, with issues involving circulation, length of preservation and overall consistency. It is estimated that of the 600,000 that died in the war, 40,000 were embalmed.

Business was doing so well that the War Department was forced to issue General Order 39 to ensure only properly licensed embalmers could offer their services to mourners. But the technique was limited to the war – to make embalming part of a traditional American funeral would require Abraham Lincoln, who you might say was an early adopter.

Lincoln’s ‘lifelike’ death

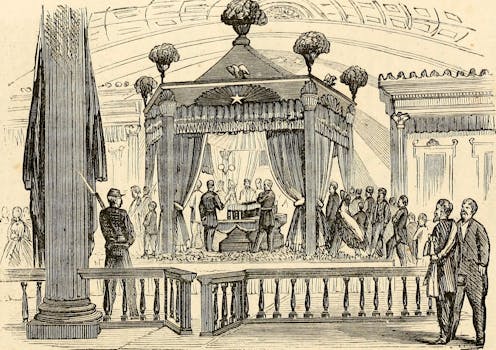

Many prominent Civil War officers were embalmed, including the first casualty of the war, Colonel Elmer Elsworth, who was laid in state in the East Room of the White House at Lincoln’s request.

Upon the death of Lincoln’s 11-year-old son Willie in 1862, he had the boy’s body embalmed. When the president was assassinated three years later, the same doctor embalmed Lincoln in preparation for a “funeral train” that paraded his body back to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois. Nothing like this had happened for any president previously, or since, and the funeral procession left an indelible effect on those who attended it. Most visitors waited in line for hours to parade by Lincoln’s open casket, usually set up in a State House or rotunda after being unloaded from the train.

Lincoln’s appearance early in the trip was apparently so lifelike that mourners often reached out to touch his face, but the quality of the preservation faded over the length of the three-week journey. William Cullen Bryant, editor of The New York Evening Post, remarked that after a lengthy viewing in Manhattan, “the genial, kindly face of Abraham Lincoln” became “a ghastly shadow.”

This was the first time most Americans saw an embalmed body, and it quickly became a national sensation.

Death becomes professionalized

The public was painfully aware of death, with an average life expectancy of around 45 years (almost entirely due to an infant mortality rate higher than anywhere on Earth today). Seeing a corpse that exhibited lifelike color and less rigid features made a strong impression.

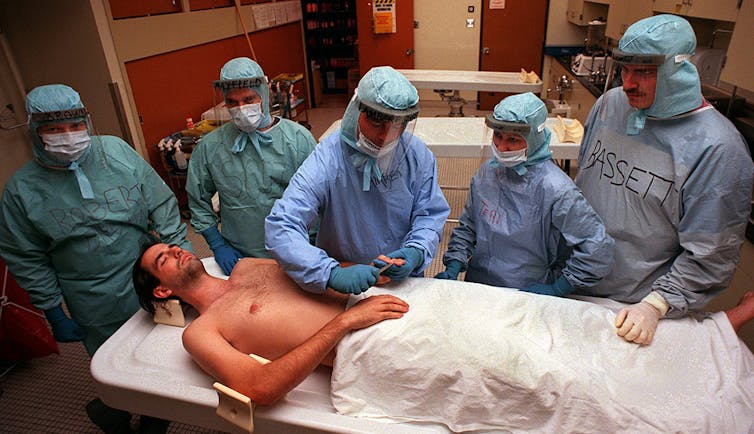

While we do not have statistics on the increase in embalmings during this time, there is ample evidence that the Civil War had a profound effect on how Americans treated death. Victorian mourning traditions gave way to funeral homes and hearses. Local carpenters and taxi services began offering funerary services, and undertakers earned “certificates of training” from embalming fluid salesmen. Eventually, every American could be embalmed, as most are today.

There was one potent caveat: Families could no longer bury their own. More was needed than the assistance of friends and family to inter a corpse. Death was becoming professionalized, its mechanisms increasingly out of the hands of typical Americans. And as a result, the cost of burying the dead soared. The median cost of a funeral and burial, including a vault to enclose the casket, reached US$8,508 in 2014, up from about $2,700 three decades ago.

Thus was born the American funeral industry, with embalming as its cornerstone, as families ceded control of their loved ones’ bodies to a funeral director.

Differences with other cultures

When people talk of a “traditional” American funeral today, they usually refer to a cosmetized, embalmed body, presented in a viewing before being interred in a cemetery.

This unique approach to interment is unlike death rites anywhere else in the world, and no other country in the world embalms their dead at a rate even approaching that of the U.S. Funeral tradition involves the intersection of culture, law and religion, a recipe that makes for very different outcomes across the globe.

In Japan, nearly everyone is cremated. That doesn’t mean it’s cheap: The cultural traditions bound to the ceremony, which include family members passing cremated bone remains to each other using chopsticks, predate the Civil War.

In Germany, where cremations are also increasingly popular, the law requires that bodies be interred in the ground – even cremated remains –including the purchase of a coffin and a land plot. This has led to “corpse tourism,” in which cremation is outsourced to a neighboring country and the body shipped back to Germany.

Other European countries struggle to deal with limited land resources for burial, with countries such as Greece requiring that graves are “recycled” every three years.

In Tunisia, as with all majority Muslim countries, nearly everyone is interred in the ground within 24 hours, in a cloth shroud and without chemical embalming. This is in accordance with Islamic scripture. It also bears close resemblance to the original interment of Americans before the Civil War.

Time to make plans

While American funerals are typically more expensive than in other countries, U.S. citizens enjoy many more options – and can even choose a simple Muslim-style interment. The key thing is to plan ahead by thinking critically about how you want yourself or your loved ones interred.

If you were to die in 2017, chances are you would meet your demise at the hospital. Your family would be asked if they had an “advanced directive” regarding “disposition of remains.” In the absence of clear guidelines, your next of kin would most likely sign away the rights to your body to a local funeral parlor that will encourage them to have the body embalmed for a viewing and burial.

You would be interred with the blood and organs of your body replaced with carcinogenic preservative liquids, heavily cosmetized to hide the signs of the the embalming surgery that rendered you this way. Your embalmed body would be placed in an airtight casket, itself placed inside a concrete vault in the ground.

And you may wish for it to be that way. But if you prefer anything else, you must make your wishes known. To say “I don’t care, I’ll be dead” places an undue burden on your family, which is already mourning your loss.

Brian Walsh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Hezbollah − degraded, weakened but not yet disarmed − destabilizes Lebanon once again

Hezbollah’s entry into the current war followed the killing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The group has…

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

When unpaid cooking, cleaning and child care get a dollar value, income inequality in the US shrinks

Women’s unpaid work at home has declined much more than men’s contributions have increased.