How companies can learn to root out sexual harassment

Human resources professionals should be trained at school and encouraged on the job to take employee complaints seriously. But that's not how the profession works now.

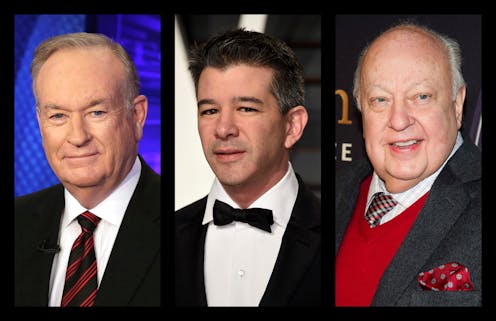

Fox News renewed its contract with former host Bill O'Reilly earlier this year despite knowing that he had just settled an expensive sexual harassment case, according to recent revelations.

Given this and other tales of bosses accused of harrasment, many Americans are surely wondering what companies can do to stop and stave off harassment. As organizational psychologists who have researched toxic work environments and consulted on related issues for years, we believe that it is possible.

The key, we’ve found, is to build organizational cultures where people fear the consequences of not speaking up more than they fear the consequences of remaining passive and silent. In short, human resources departments need to change their ways.

A workplace menace

The scourge of sexual harassment has been getting ample media attention in recent weeks amid a raft of stories reporting allegedly abusive behavior by, among others, show business executive Harvey Weinstein, screenwriter and director James Toback, celebrity chef John Besh and Amazon Studios executive Roy Price.

Most recently, The New York Times reported that O'Reilly struck a US$32 million deal to settle sexual harassment allegations just weeks before Fox News gave him a new four-year contract. O'Reilly, who denies doing anything improper, was fired in April after the network investigated multiple allegations against him.

Fox News has been contending with sexual harassment scandals enveloping not just O'Reilly but many more of its executives and hosts for more than a year. The network’s management faces pressure from its owner to end what appears to be an institutional culture that has treated unwanted sexual advances and misogyny as routine.

Underreporting

Even with all this attention, sexual harassment remains a poorly understood concept that often remains in the dark.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the federal agency tasked with enforcing laws barring discrimination against job applicants and employees, has a solid definition.

“Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance, or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment.”

Yet most victims don’t report incidents. An EEOC task force estimated in 2016 that anywhere from 25 percent to 85 percent of American women have experienced harassment on the job.

Researchers have found that sexual harassment can make people less engaged with their work and less satisfied with their jobs. It may also cause physical and mental illnesses, including post-traumatic stress disorder. The long-term psychological harm is one reason why harassment victims may prove reluctant to file formal claims.

Sexual harassment on the job is also costly in monetary terms and to a company’s reputation. Employers paid about $125 million in 2015 and 2016 to settle claims through the EEOC. That doesn’t include claims that ended up in court or those, like the ones involving O'Reilly, which were settled confidentially and can lead to big payouts.

Workplace culture

So what can companies do to root out the bad behavior of some bosses? First it helps to consider the types of workplaces where harassment is most common and why more people who witness it don’t speak out.

Studies have determined that sexual harassment is most common in male-dominated industries, such as construction, where women are underrepresented. Even when famous movie stars experience harassment, they may attribute their silence to a lack of faith that their employer or other authorities will believe them and take their complaint seriously. Many develop a sense of shame and fear career damage – including job loss.

Uber’s debacle is a case in point. Until a former employee exposed the company’s entrenched sexual harassment problems – leading to the CEO’s ouster – Uber’s culture and human resources team tolerated them.

In contrast, female-dominated and gender-balanced fields such as education harbor less tolerance of this behavior.

These patterns point to how employers can rid their workplaces of this problem and encourage witnesses to sound the alarm.

For starters, employers can adopt and enforce strong anti-harassment policies and train staff to recognize and report instances of this behavior.

But making a real difference demands more than formal policies and practices, which won’t on their own deter perpetrators or make victims speak out unless employees believe their employer is serious about enforcing them. Bystanders won’t do their part either if they think they’ll experience backlash for offering their help and support.

And as one of us (Katina Sawyer) found in her recent work, powerful men can help rid their companies and organizations of gender inequality and sexism by being good allies to the women they work with.

Best practices

We believe workplace leaders can help by improving their organization’s informal culture. Here are four ways that senior managers can actively signal their commitment to stopping sexual harassment and other forms of discrimination:

- Participate in and even present at sexual harassment training sessions.

- Attend conferences and workshops geared toward preventing sexual harassment.

- Create and protecting anonymous reporting channels.

- Hold HR managers accountable for enforcing these policies, aiding victims and encouraging bystanders to speak up.

When workplace leaders truly lead, victims feel more empowered to report their experiences and bystanders become more likely to intervene. Perpetrators, in turn, realize they could be punished or fired over sexual harassment, making them less likely to do it.

Fixing HR

In addition, the profession of human resources – usually the first place a victim of harassment will go to find support – needs to change.

That’s because, beginning in college and graduate school, HR professionals learn to worry more about protecting employers from anti-harassment lawsuits than rooting out the misogyny that makes the perpetrators of harassment feel free to prey on their victims.

In addition, HR departments seem to treat harassment training as more of a box to tick rather than an important message to employees that this behavior is both wrong and illegal.

Instead, these professionals should be trained at school and encouraged on the job to create and promote the conditions that deter harassment. They can do so by encouraging reporting and leaving no doubt that management will take complaints seriously.

They should never fail to follow through on harassment claims or enforce harassment policies. Letting them go or even giving employees accused of this behavior a raise – as Fox did with O'Reilly – signals tolerance to perpetrators, victims and bystanders.

Reporting the problem, in other words, should be encouraged and not punished in any formal or informal way.

Once victims and bystanders feel that it’s safe for them to report harassment and other outrages, it won’t take decades for powerful men like O'Reilly, Weinstein and Toback to be held accountable for their alleged misdeeds. Otherwise, harassment is bound to remain underreported and pervasive.

Christian Thoroughgood works and consults for MotiveX Solutions.

Katina Sawyer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

AI and 3D printing help researchers create heat- and pressure-resistant materials for aerospace and

AI models are designing new metal alloys that have been 3D-printed and tested in the lab. The results…

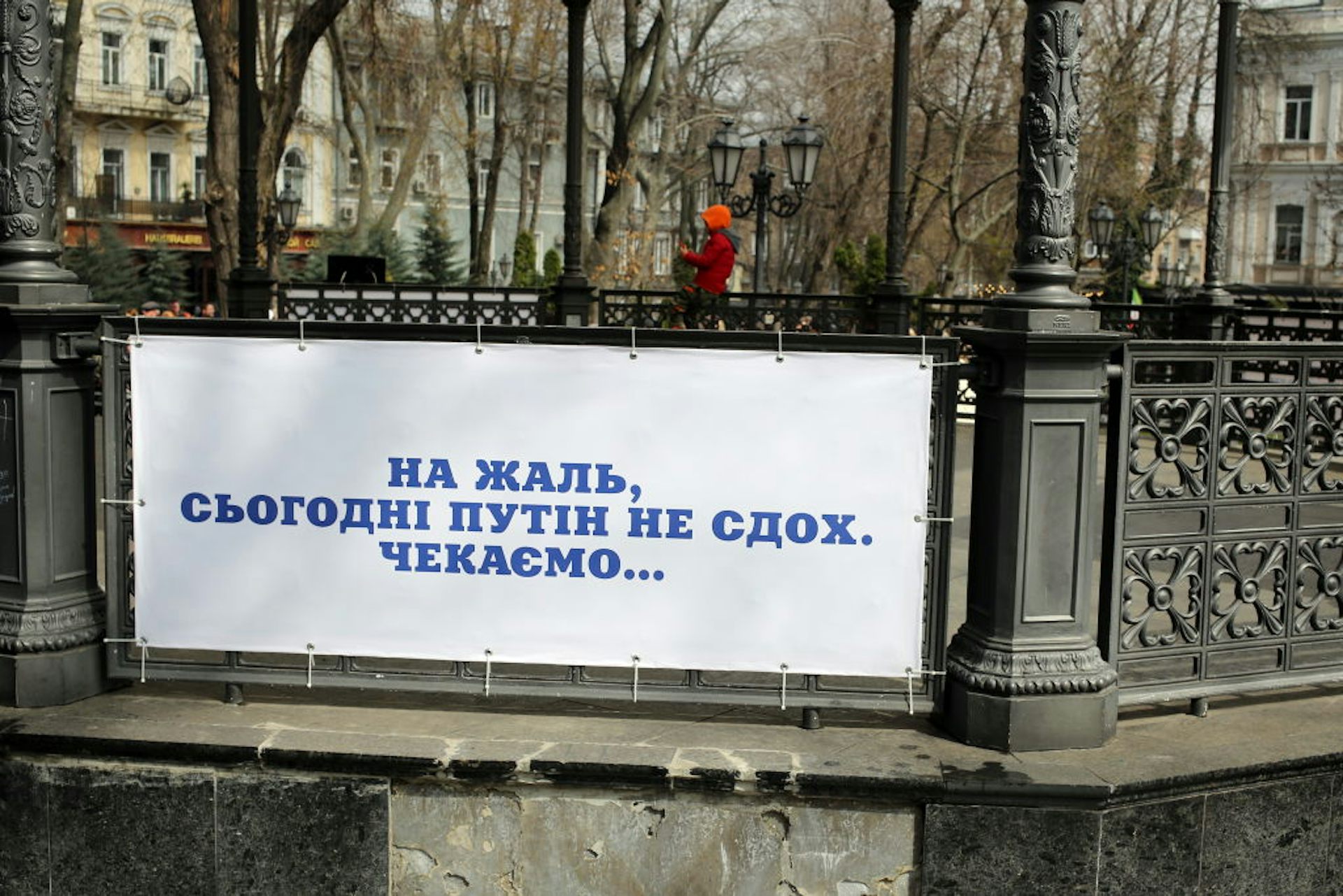

Front lines of humor: Dark humor voices Ukrainians’ hopes for victory

Humor has served many functions since Russia’s full-scale invasion, from providing Ukrainians with…

Brazilian jiu-jitsu is having its #MeToo moment

With legend Andre Galvao accused of sexual misconduct, gyms and athletes have been forced to confront…