Amazon's Whole Foods deal could still fall apart thanks to forgotten antitrust case

The deal escaped scrutiny because the two aren't direct competitors, yet Amazon's huge marketing platform will help Whole Foods steamroll rivals. In the past, the Supreme Court has said this violates antitrust law.

Amazon formally takes ownership of Whole Foods after the Federal Trade Commission signaled on August 23 that it wouldn’t stop the deal.

The online retailer isn’t wasting any time remaking the high-end grocery chain in its low-price image. Its first act involved cutting prices on dozens of items, from avocados to tilapia. But that is not what is sending shivers down the aisles of rival food retailers like Walmart, which now controls 20 percent of the grocery market by pursuing just such a low-price strategy.

The reason, which the FTC ignored in providing its imprimatur, is that Amazon gives Whole Foods access to an online marketing platform that no other grocery company, even a behemoth like Walmart, can hope to reproduce.

My research suggests that only a few decades ago the FTC would have used antitrust law to block the deal – and it still has the power to do so.

Predatory promotion

Everyone knows that Amazon is the biggest online retailer. The company handles 43 percent of all internet purchases in the U.S., attracting so much business that its website is actually the country’s fifth-most trafficked.

But not everyone realizes that Amazon is also the king of online product search. By offering a huge range of products – almost 400 million – Amazon entices more than half of online shoppers to bypass the usual search gatekeepers and start their product hunt directly on its website.

Whole Foods will now have exclusive access among grocery retailers to this enormously valuable search engine. And it will be near impossible to compete with a company whose products and grocery delivery services can be ordered directly through a website that America already uses for nearly half of its online shopping.

That is bad for consumers because it means that Whole Foods may come to dominate the grocery world not by offering better products for the best prices, as you’d find in a well-functioning market, but because of the promotional advantage that comes from its tie-up with Amazon.

Congress passed the Clayton Act in 1914 to handle just this situation. The act tasks antitrust regulators with blocking acquisitions for which “the effect … may be substantially to lessen competition.” You might therefore have expected the FTC, which reviews mergers in the grocery industry, to take a special interest in this deal.

You’d be wrong, of course, because since the early 1980s antitrust regulators at the FTC and Justice Department have taken a narrow approach to merger enforcement, generally treating only large deals between direct competitors as a potential threat to competition.

That explains why the FTC approved the Whole Foods deal with lightning speed. Since Amazon had almost no presence in the grocery industry when it inked the agreement, it didn’t qualify as a direct competitor.

In the 1960s and ‘70’s, however, things were different, as I show in a recent paper. During that time, the FTC fought a remarkable campaign to prevent companies from using promotional advantages to colonize new markets. Among the FTC’s victories in its battle against such “predatory promotion” were its reversals of household products giant Procter & Gamble’s acquisition of Clorox bleach and General Foods’ purchase of S.O.S., the scrub pad maker.

Like Amazon, both P&G and General Foods acquired companies in markets in which they were not yet direct competitors. Like Amazon, both could leverage their vast product lines to offer their new acquisitions a massive promotional advantage. The difference is that back then P&G and General Foods had a sizable advantage in television advertising, rather than online search traffic, because their extensive product portfolios allowed the companies to negotiate bulk discounts from the major networks.

The legal precedents created by those cases give the FTC a basis for unwinding the Amazon Whole Foods deal but have been ignored for decades by federal antitrust enforcers.

Lessons from the case against P&G

The FTC’s case against P&G is particularly relevant today. Filed in 1957 shortly after the Clorox purchase closed, it established for the first time that, as the Supreme Court put it, an acquisition that creates “huge assets and advertising advantages” can violate antitrust law.

P&G’s product line was so large, extending from Ivory soap to Duncan Hines cake mix, that it was already the nation’s largest national TV advertiser. This allowed P&G to negotiate bulk discounts on advertising time that it could pass on to Clorox.

The FTC feared that those discounts would give Clorox privileged access to the dominant marketing platform of the era. When Americans tuned in to the Big Three television networks, they would see Clorox, and only Clorox, for sale, much as when Americans use Amazon to search for groceries online, they will see only Whole Foods groceries available for delivery.

The FTC filed suit to unwind the deal, arguing that P&G would drive competitors from the market, not because those competitors offered an inferior product – all bleach is chemically identical – but because P&G had a promotional advantage. Similarly, Whole Foods will be able to use Amazon’s website to swallow up market share, even though its rivals also offer similar services and products, such as organic produce and online ordering.

After an initial setback, the FTC won its case in the Supreme Court in 1967, establishing a precedent for the first time that mergers that create massive promotional advantages can violate the law, even when there is no direct competition between the target and acquiring companies.

Reversing course

President Ronald Reagan cut short this campaign against predatory promotion in the early 1980s by appointing new officials to the FTC who argued that promotion is good for consumers, regardless of whether it confers an advantage on a particular competitor, because it provides consumers with useful product information. The idea has proven immune to subsequent changes in administration.

In my paper I counter that this argument rings hollow in the information age, because consumers can now get all the product information they need from myriad sources online. Making Whole Foods’ groceries searchable on Amazon’s website doesn’t increase the internet’s cache of product information – consumers can already get that on the grocer’s website – but it will steer consumers squarely toward Whole Foods’ products.

The FTC can still reverse course and block the deal after it closes, as it did in the forgotten P&G case.

If it doesn’t, then your only option for buying anything could one day be Amazon. And if that happens, textbook economics teaches that those avocados won’t stay cheap for long.

Ramsi Woodcock does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Read These Next

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…

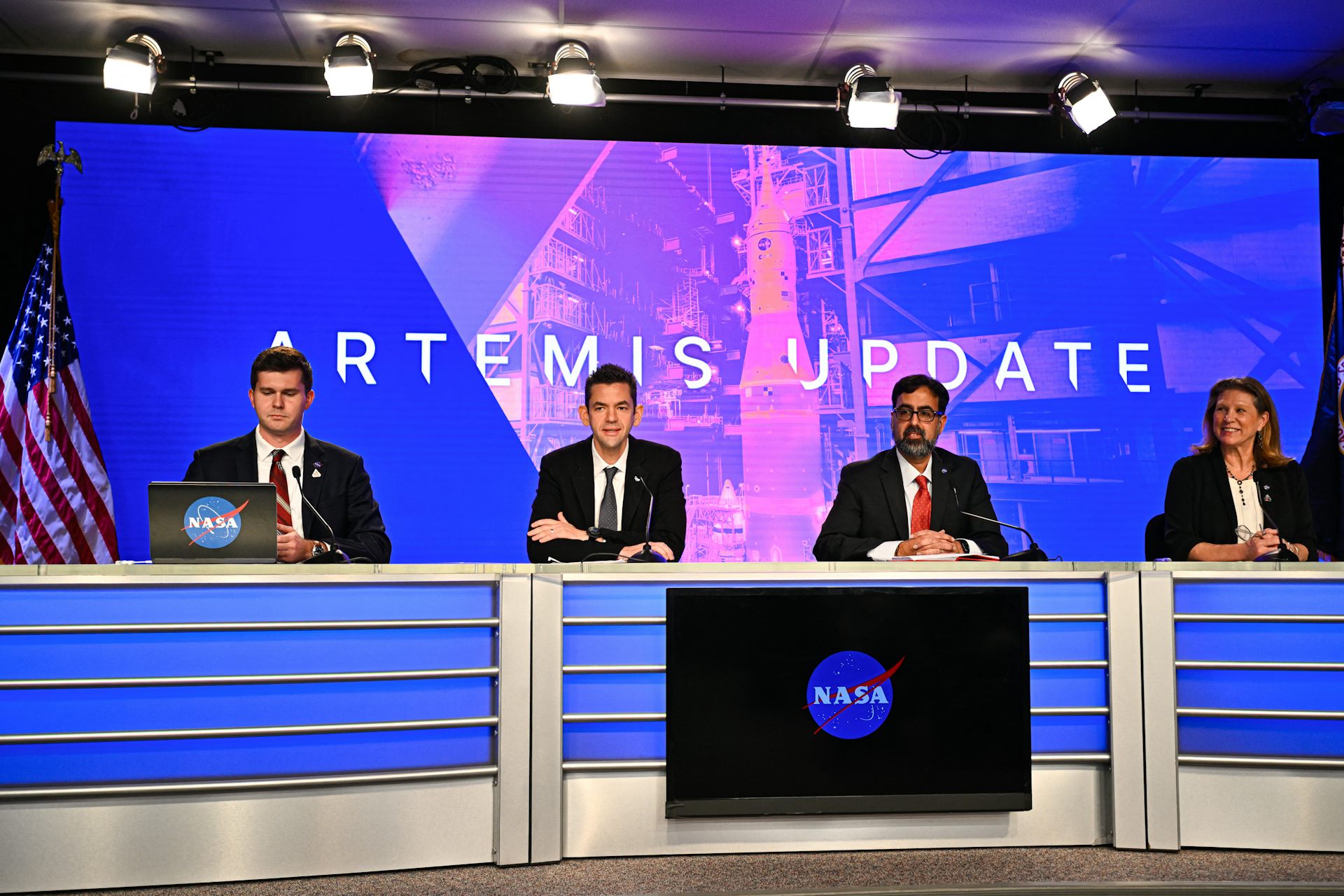

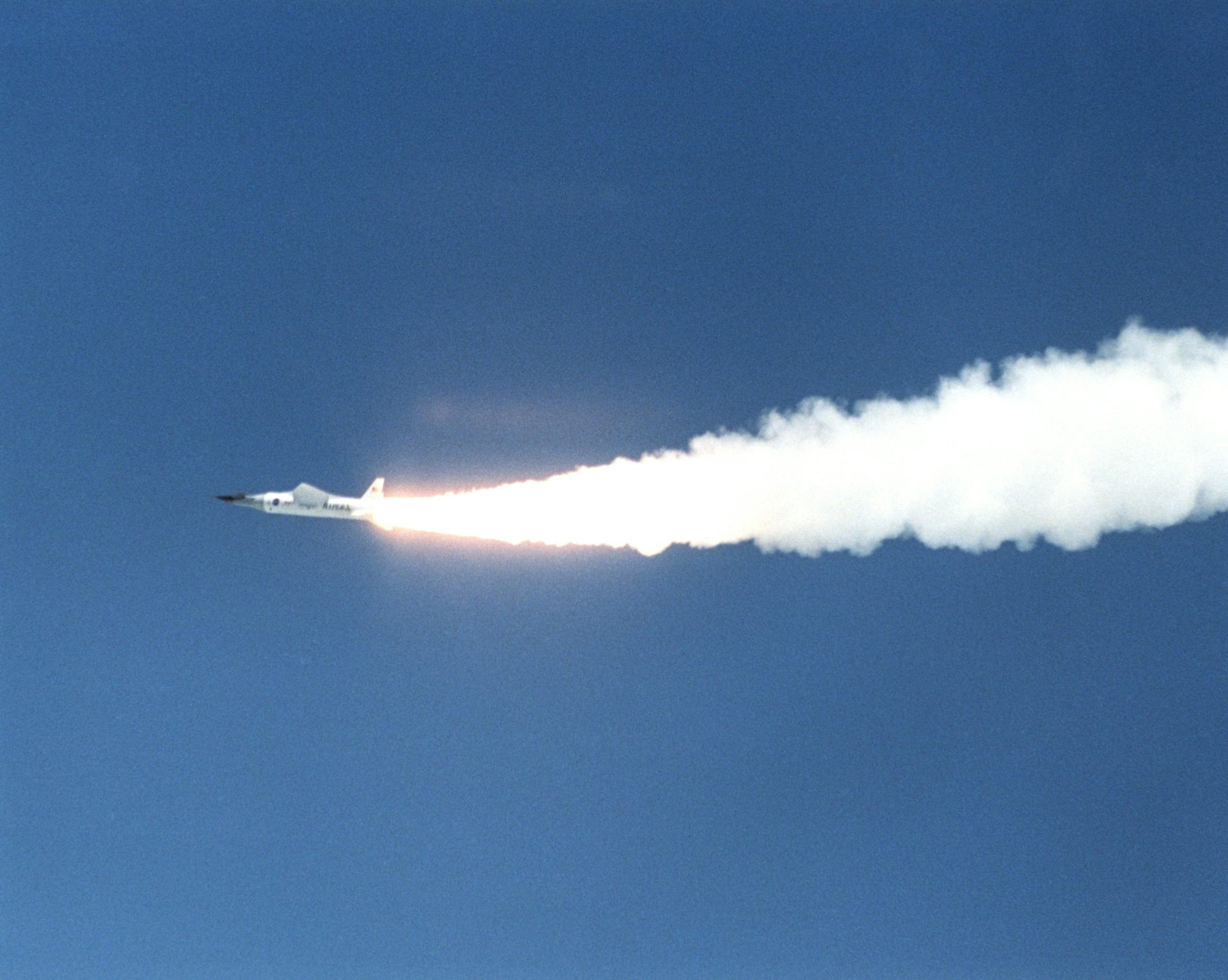

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…

AI and 3D printing help researchers create heat- and pressure-resistant materials for aerospace and

AI models are designing new metal alloys that have been 3D-printed and tested in the lab. The results…