How food assistance programs can feed families and nourish their dignity

Free food may fill your stomach, but it doesn’t always satisfy the desire to feel fully human.

The 2025 government shutdown drew widespread attention to how many Americans struggle to get enough food. For 43 days, the more than 42 million Americans who receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits had to find other ways to stock their cupboards.

When asked how she felt about her benefits being suspended, one woman in West Virginia told a New York Times reporter, “We’re angry. Because we do count!”

Her sentiment reflects an often underappreciated fact about food. Food is not just a matter of survival. What and how you eat is also a symbol of your social status. Being unable to reliably feed your family healthy and nutritious foods in a way that aligns with your values can feel undignified. It can make people feel unseen and less important than others.

As researchers who study food inequality, nutrition and food justice, we have spent decades surveying and interviewing Americans about how they eat. We have witnessed firsthand how food assistance does help people meet their basic needs, but how it can also be stigmatizing and diminish their sense of dignity.

We have also studied alternatives to typical charitable food programs that, despite good intentions, tend to induce shame. We have learned that it is possible to help people put food on the table while preserving their dignity.

Dignity and food assistance

Addressing the root causes of food insecurity – what happens when people lack steady access to the food they need for a nutritious diet that’s in keeping with their preferences – is a persistent problem in the United States.

Thus, the demand for SNAP benefits, which help Americans buy groceries, other government nutrition programs, and food banks and food pantries rarely declines much – even when the economy is strong. Yet relying on food assistance programs does not tend to support a healthy diet and can take a toll on mental health.

As interviewers and clinicians, we have heard mothers describe the shame they feel when SNAP benefits do not cover the entire grocery bill. We have witnessed the frustration that comes with walking down a food pantry aisle lined with signs instructing hungry people to “take only 1 item!”

“The stuff looks like almost trash, but they give it to you,” one woman we interviewed said of her experience with food pantries and the like.

These kinds of stories are not uncommon. Charitable food programs receive leftover items from grocery stores, donations from community food drives and local businesses, and sometimes surplus from local farms. Food is often damaged in transport or from being handled too many times. A review of the research found that many people who use food pantries described the food as unhealthy, moldy or inedible. Being given unhealthy and unappealing food in a time of need is a double burden.

While free food may fill the stomach, it does not satisfy the desire to feel fully human and worthy of nourishment.

People who visit food banks have told researchers that they have come to expect low-quality food and few choices. When food aid is provided that way, it can leave the people it is supposed to help feeling powerless and ashamed.

These indignities are compounded by the fact that people who visit food banks and food pantries routinely face suspicion and surveillance around what they buy and how they eat, intensifying the stress associated with food insecurity.

In our research, we saw cashiers hovering over mothers using SNAP EBT cards in the self-checkout line. Politicians routinely suggest that SNAP is corrupt, contributing to nationwide perceptions that people who rely on this program are unfairly gaming the system. One study found that more than two-thirds of the Americans people who get food assistance have been the target of hostile comments and interactions from strangers at the grocery store.

Minimizing stigma

Several studies have shown that food programs do not need to sacrifice dignity to offer help. Programs that offer opportunities for people with lower incomes to receive and give back are important.

In Canada, bulk-buying food cooperatives did just that. Food assistance programs confer dignity when they make people feel good. People seeking help feel more satisfied after visiting food pantries that keep convenient hours or offer fresh produce.

SNAP has also tried to promote client dignity by ensuring that benefits are accepted in major grocery stores and distributing the funds to debit cards, allowing people to look and feel like everyday shoppers.

Yet despite these efforts social stigma persists. People who are enrolled in the SNAP program are still routinely devalued and judged for being poor in a society that assigns social value and worth based on one’s position on the economic ladder.

Cultivating dignity in food assistance

Minimizing stigma improves food assistance. Intentionally cultivating food dignity may be the next step.

Our assessment of a nationwide meal kit program demonstrated how dignity can be cultivated when food assistance programs consider the nutritional, emotional, aesthetic and cultural dimensions of food and eating.

In 2021, we conducted 116 interviews with participants of a meal kit program called Pass the Love. The program was free and anyone could enroll, no questions asked. The meal kits contained the necessary food and recipes to make three vegetarian meals a week, such as sesame coconut noodle salad or carrot coconut dal with rice. The program ran for four consecutive weeks.

When we interviewed participants about their experiences during and after the program, we learned that while they were thankful for the free food, what mattered more was the high quality, how it was packaged and how it conveyed care and respect.

Most participants had incomes at or well below the poverty line. They described what we came to call a “high dignity food experience,” meaning that it generated positive feelings and a sense of worth.

Opening the nicely packaged meal kit boxes each week felt like “Christmas,” to some people and a “gift” to others. Many found the “thought and care” that went into the program remarkable. Offering high-quality food to make nutritious, complete meals symbolized that low-income or food-insecure people deserve to eat well and feel good.

Our research, like similar studies that others have conducted, shows that treating food as a basic human right requires more than just giving people something to eat. It means ensuring unconditional access to the culturally appropriate fresh and nutritious food people need to thrive not just physically, but psychologically and socially.

Joslyn Brenton received funding from Partnership for a Healthier America as an external research expert.

Dr. Virudachalam received funding from the Edna G. Kynett Memorial Foundation, Rite Aid Foundation, and Partnership for a Healthier America in the last 36 months. She is a member of The Food Trust Board of Directors, the National Produce Prescription Collaborative Steering Committee, and Philadelphia City Council's Food and Nutrition Security Task Force.

Alyssa Tindall does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Coffee crops are dying from a fungus with species-jumping genes – researchers are ‘resurrecting’ the

Coffee wilt disease has continually devastated farms around the world. Understanding the fungus’s…

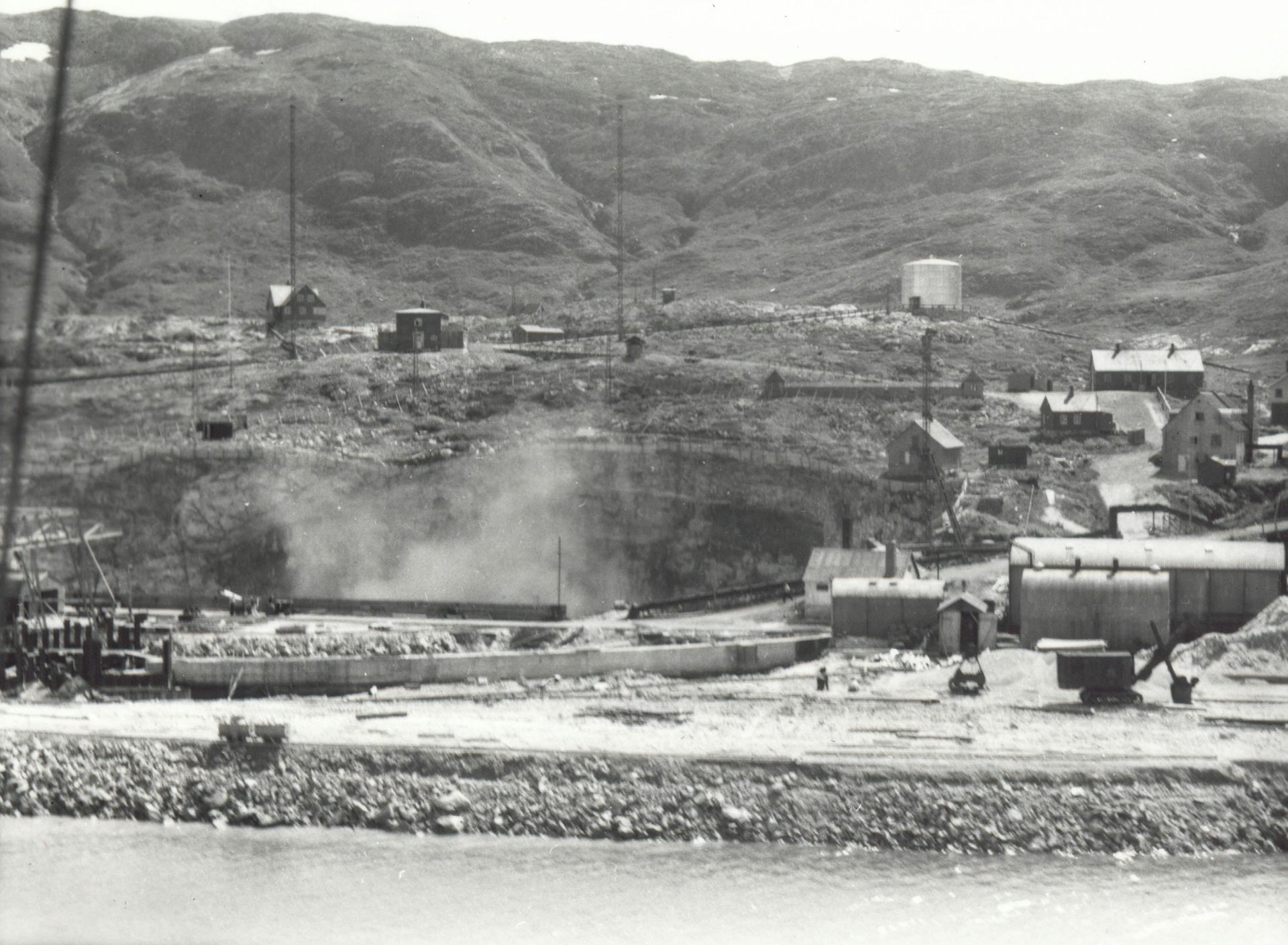

In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

Strategic resources have been central to the American-led global system for decades, as a historian…

Revisiting the story of Clementine Barnabet, a Black woman blamed for serial murders in the Jim Crow

In 1912, a young Black woman’s supposed religious beliefs were quickly blamed to make sense of a terrifying…