$2B Counter-Strike 2 crash exposes a legal black hole: Your digital investments aren’t really yours

An overnight update to Counter-Strike 2 erased billions of dollars in valuable digital assets that players had accumulated. The law gives them almost no recourse.

In late October 2025, as much as US$2 billion vanished from a digital marketplace. This wasn’t a hack or a bubble bursting. It happened because one company, Valve, changed the rules for its video game Counter-Strike 2, a popular first-person shooter with a global player base of nearly 30 million monthly users.

For years, its players have bought, sold and traded digital cosmetic items, known as “skins.” Some rare items, particularly knives and gloves, commanded high prices in real-world money – up to $1.5 million – leading some gamers to treat the market like an investment portfolio. As a result, many investment-style analytics websites charge monthly fees for financial insight, trends and transaction data from this digital marketplace.

In one fell swoop, Valve unilaterally changed the game. It expanded the “trade up contract,” allowing players to exchange – or “trade up” – a number of their common assets into knives or gloves.

By flipping this switch, Valve instantly upended digital scarcity. The market was flooded with new supply, and the value of existing high-end items collapsed. Prices plummeted, initially erasing half the market’s total value, which exceeded $6 billion before the recent crash. Although a partial recovery brought the net loss to roughly 25%, significant volatility continues, leaving investors unsure whether the bottom has truly fallen out.

Many of those who saw their digital fortunes evaporate immediately wondered whether there was anything they could do to get their money back. Speaking as a law professor and a gamer myself, the answer isn’t what they want to hear: no. In fact, the existing legal structure largely protects Valve’s ability to engage in this sort of digital market manipulation. Players and investors were simply out of luck.

The Counter-Strike 2 crash reveals a troubling reality that extends far beyond video games: Corporations have built exchange-scale investment markets governed primarily by private terms-of-service agreements, rather than the robust set of public regulations that oversee traditional financial and consumer markets. These digital economies occupy a legal blind spot, lacking the fundamental guardrails of property rights, meaningful consumer protection or even securities regulation.

Your digital ‘property’ isn’t really yours

If you spend real money on a digital item, it may feel like you should own it. Legally, you don’t.

The digital economy is built on a crucial distinction between ownership and licensing. When users sign up for Steam, Valve’s platform, they agree to the Steam subscriber agreement. Buried in that contract is a critical piece of legalese stating that all digital assets and services provided by Valve, including the Counter-Strike 2 skins, are merely “licensed, not sold.” The license granted to users “confers no title or ownership” at all. This isn’t meaningless corporate jargon; it’s a legal standard routinely affirmed by U.S. courts.

The legal implication is clear: Because players only license their skins, they have no property rights over them. When Valve changed the game’s mechanics in a way that collapsed the items’ market value, it didn’t steal, damage or destroy anyone’s “property.” In the eyes of the law, Valve simply altered the conditions of a license, something that its terms-of-service agreement allows it to do unilaterally, at any time, for any reason.

Consumer protection laws don’t apply

While the Counter-Strike 2 crash may seem like a violation of consumer rights, current laws are ill-equipped to handle this type of corporate behavior.

Lawmakers have begun addressing concerns about digital goods, primarily focusing on instances where purchased movies or games disappear entirely from user libraries. For example, California recently enacted AB 2426. This law requires transparency, prohibiting terms like “buy” or “purchase” unless the consumer confirms that they understand they will receive only a revocable license.

As commendable as this law is, it protects only against confusion and loss of access, not loss of market value when platforms rebalance virtual economies. Valve can comply with consumer transparency laws and still adjust the supply of digital items, rendering them valueless overnight. Ultimately, current consumer protection laws are designed to ensure users know what they are licensing. They do not, however, create ownership interests or protect the speculative value of those digital items.

Game items are treated like unregulated stocks

Perhaps the most significant legal vacuum is the absence of financial regulation. The Counter-Strike 2 economy, a multibillion-dollar ecosystem with dedicated investors and third-party cash markets, looks and behaves like a traditional financial market. Yet, it remains outside the purview of any financial regulator, such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Under U.S. law, the primary standard for determining whether an asset should be governed as a security is the Howey test. According to this Supreme Court precedent, an asset is a security if it meets four criteria. Securities involve an “investment of money” in a “common enterprise” with a reasonable expectation of “profits” derived from the “efforts of others.”

Counter-Strike 2 skins arguably meet all of these criteria. Participants invest real money in a common enterprise – Valve’s platform – with an expectation of profit. Crucially, that profit depends on the “efforts of others.” The SEC notes this prong is met when a promoter provides “essential managerial efforts” that affect the enterprise’s success. Valve controls the game’s development, manages the platform and – as the recent update proves – dictates item supply and scarcity.

If a publicly traded company unilaterally changed its rules in a way that predictably tanked the price of its own shares, regulators would immediately investigate for market manipulation. So how can Valve get away with this? Three things cut against the skins’ status as securities.

First is their “consumptive intent” – skins are primarily game cosmetics. Second, there’s no way to convert the skins into dollars within Valve’s own ecosystem. In other words, third-party markets allow users to cash out, but these markets operate outside Valve’s own immediate control. And finally, the Howey test generally governs assets, such as stocks and bonds, that grant investors enforceable rights. Valve’s licensing scheme attempts to circumvent this by ensuring players hold nothing but a revocable license.

In my view, the $2 billion crash is a wake-up call. As digital economies grow in financial significance, society must decide: Will these markets continue to be governed solely by private corporate contracts? Or will they require integration into more robust legal frameworks, such as securities regulation, consumer protection and property law?

João Marinotti does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

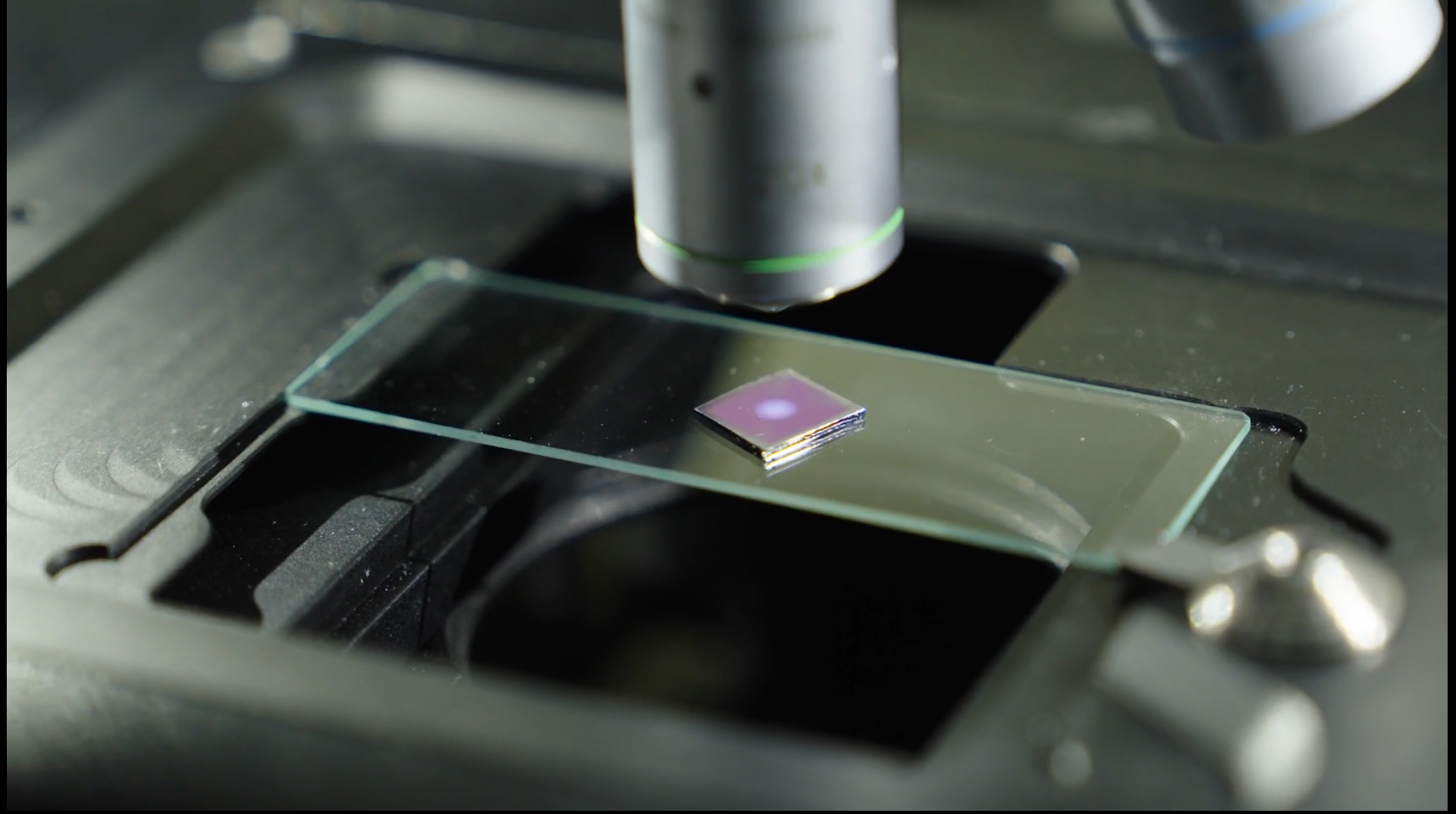

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and

Tiny particles bounce light around in a unique way, a property that researchers are using to detect…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…