Misspelled names may give brands a Lyft – if the spelling isn’t too weird

Consumers perceive some misspellings positively, but only if the unconventional spelling is relevant and not too extreme, according to a new study.

Consumers don’t mind when companies use misspelled words – think Lyft for “lift” or Froot Loops for “fruit loops” – as their brand names, as long as the alterations aren’t too extreme and the misspelling makes sense.

Those are the main findings of a new peer-reviewed paper I published with fellow marketing scholar Leah Warfield Smith. This builds on previous work that found that using misspelled brand names usually backfires.

Misspelled brand names like Kool-Aid, Reddi-wip and Crumbl seem to be everywhere. They are especially common in the names of smartphone apps and in certain industries, like fashion. Companies often do this to stand out or perhaps so they can use the misspelled word as their domain name.

Despite their popularity, we know little about how consumers respond to different types of misspelled names, especially when those names deviate significantly from correct or standard spelling. Our study aims to fill this gap.

In a series of six experiments, we tested consumer reactions to fictional and several real brand names with varying levels and types of misspellings.

Mild misspellings, such as combining two real words such as SoftSoap were perceived just as positively as correctly spelled names. When consumers saw different levels of misspellings – consider the brand names Eazy Clean, Eazy Klean and Eezy Kleen – they reacted more negatively the further the name deviated from the correct spelling “easy clean.”

However, we also found that relevance matters. A misspelled name that aligns with the product or brand identity can still be successful. For example, consumers responded just as well to Bloo Fog – a playful nod to Oolong tea – as to the correctly spelled “blue fog.” In contrast, Blewe Fog – a misspelling without a linguistic connection to the product’s name – performed worse.

Other experiments showed similar, more positive effects when the name related to the owner’s identity, for example Sintymental Moments by Joe Sinty, or a visual cue as in Toadal Fitness with a toad logo. In each case, the misspelling was more acceptable when it made conceptual sense to consumers.

Why it matters

The findings suggest that two main concepts play a role in how consumers process brand names: linguistic fluency – or how easily a name is pronounced and read – and conceptual fluency – how easily the meaning of a name is understood or how well it aligns with the product.

Linguistic fluency decreases with more severe misspellings, resulting in more negative responses. But if the misspelling adds some kind of meaning – related to the product, person or logo - these adverse effects can be easily mitigated.

For marketers and brand strategists, the takeaway is that misspellings can work, but only when they make sense. Naming a tea brand Bloo Fog might succeed where Blewe Fog fails, but only if consumers understand the name-product connection. Understanding when a misspelling helps or hurts a brand is crucial to crafting the right brand name; ideally, one that can be perceived positively while reaping the benefits of misspellings, such as increased memorability, uniqueness or trademark acquisition.

What still isn’t known

While this research uncovers how consumers react to different types of misspellings, it leaves open important questions about long-term effects. For example, do consumers still notice the misspelling in a 60-year-old brand name like Kwik Trip, a convenience store chain in the Midwest?

We also do not know how the effects of misspellings play out across different languages, cultures or product categories.

The Research Brief is a short take on interesting academic work.

Annika Abell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

50 years ago, the Supreme Court broke campaign finance regulation

A gobsmacking amount of money is spent on federal elections in the US. The credit or blame for that…

When civil rights protesters are killed, some deaths – generally those of white people – resonate mo

From the civil rights era of the 1960s until today, white victims of government violence have received…

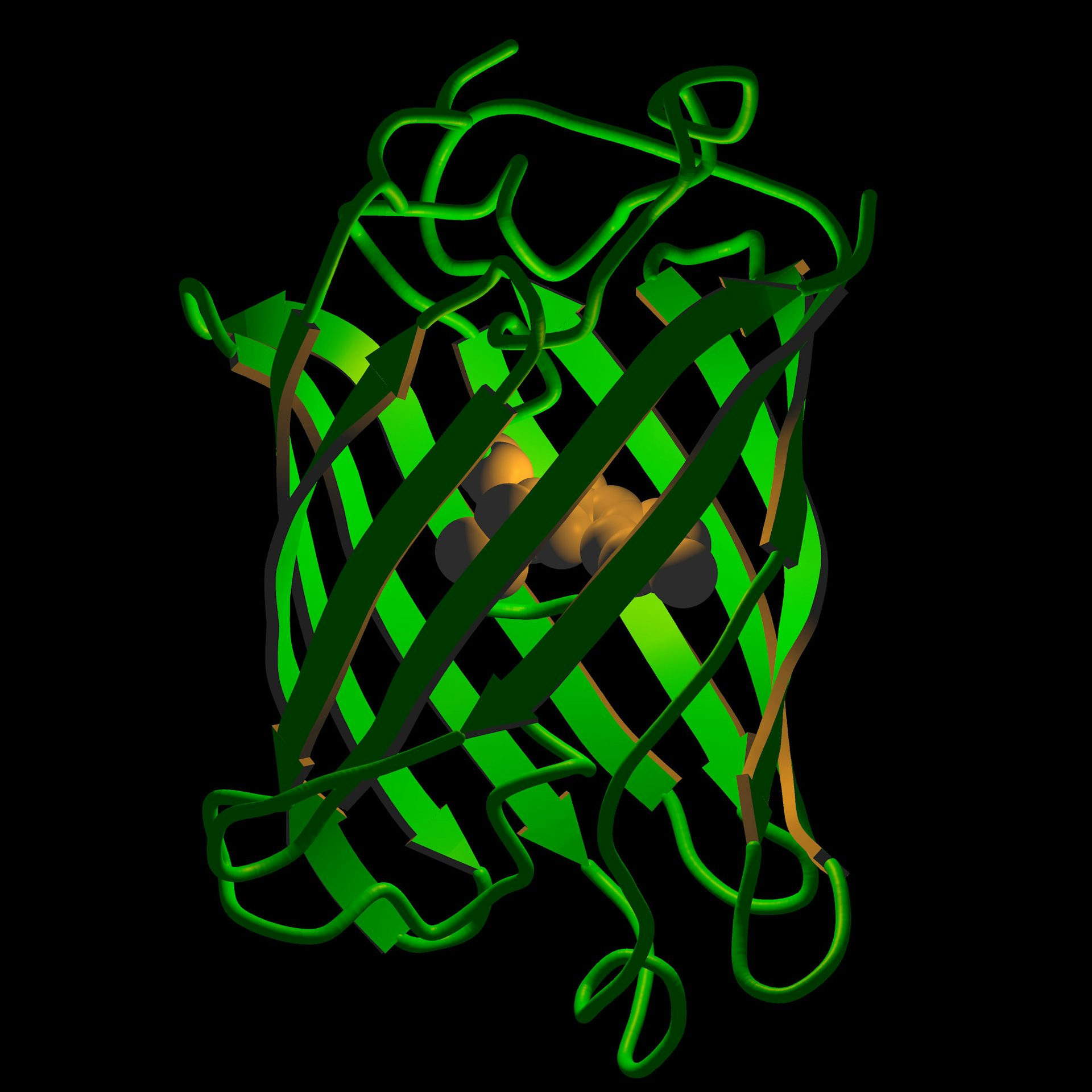

1 protein to rule them all – why crowning the protein that makes jellyfish glow green as a model can

Researchers have been studying tens of thousands of proteins and even more variations without a yardstick…