Michigan’s thousands of farmworkers are unprotected, poorly paid, uncounted and often exploited

Michigan’s migrant farmworkers are the backbone of the country’s second-most diverse agricultural economy. Social and labor protections for them fall short.

Michigan is famous for its fruit festivals. Visitors can sample cherries at the National Cherry Festival in Traverse City or blueberries at the National Blueberry Festival in South Haven.

The Apple Festival in Charlevoix and the Romeo Peach Festival feature fruit later in the season.

As a diverse crop-producing state and the top producer of asparagus in the country, Michigan has an agricultural scenery that is a picturesque blend of crop fields and fruit trees.

However, beneath this facade lies a harsh reality of precarious work and exploitative labor practices for Michigan’s farmworkers, who are often invisible to people who enjoy the fruits of their labors, according to the Michigan Farmworker Project’s ongoing research.

Few consumers are aware of the migrant and seasonal farmworkers who make this economy possible. In 2013, the last year for which official records exist in Michigan, the state saw close to 94,000 migrant and seasonal farmworkers. That count included their family members and children.

The state has not invested in counting workers in more than 10 years, a necessary step to improve their work and living conditions. Michigan recently released a request for proposals to undertake a new enumeration study this year.

In 2019, we launched the Michigan Farmworker Project as an academic collaboration with community and state organizations. The goal of the project is to increase understanding of the social, labor and housing situation of farmworkers in the state.

We aim to inform sustainable and effective policies, programs and health-promoting interventions to improve the work and living conditions for farmworkers in the state.

Critical labor

Agricultural work is year-round, with workers often rotating between different crops and locations as the seasons change. These workers carry out a vast array of essential agricultural tasks such as planting, harvesting, pruning, packing, washing produce, applying fertilizers and spraying pesticides.

Their labor is critical to maintaining the state’s robust US$104.7 billion annual agricultural economy. Yet their presence and essential contributions often go unnoticed by many Michiganders and policymakers.

The farmworkers’ invisibility stems from policies and practices that violate basic human rights through racism, exclusion and segregation that deny them social and labor protections afforded to other worker populations.

Historical federal policies like Jim Crow and the New Deal contributed to structural racism and pervasive occupational segregation that have continued until today through policies that intentionally exclude farmworkers from basic labor protections conferred to other work sectors.

Various pieces of federal and state legislation have excluded or provided minimal labor protections for farmworkers, including the National Labor Relations Act, which excludes farmworkers from protections for worker organizing and collective bargaining. Michigan law also lacks labor organizing protections for farmworkers.

The Fair Labor Standards Act is another law that applies differently to farmworkers. Under federal law and Michigan state laws, farmworkers are exempt from overtime compensation requirements, and those who labor on certain small farms are not guaranteed a minimum wage. In addition, children as young as 13 are allowed to work in the fields, compared with 16 in other industries.

Farmworkers lack overtime compensation, sick leave and holidays, and many do not have access to social benefits like Medicaid and food stamps. Many are still paid by piece-rate, earning just pennies per bucket of produce.

Even though Michigan law mandates minimum wage for piece-rate workers, our research has found that employers often fire those who fail to meet productivity quotas.

In 2010, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission investigated allegations about conditions faced by farmworkers and found that substandard living and working conditions for many had not significantly improved in 45 years.

Subsequent commission progress reports, along with our own recent research, indicate that little progress has been made during the pandemic and beyond.

This ongoing lack of improvement underscores the persistent challenges and exploitation faced by farmworkers in Michigan.

Why precarious work and labor exploitation matter

Our project uncovered that the working conditions for farmworkers are not just precarious but often exploitative.

As public health researchers, we define exploitative labor practices as those that take harmful advantage of a worker’s vulnerabilities — whether psychological, physical, sexual, social, economic or legal — to achieve financial gain. Workers often endure labor exploitation because of their economic needs and exclusion from policies that would ensure protection and safety as it is conferred to other occupations.

We find that labor exploitation of Michigan farmworkers includes excessive and unpredictable work schedules, penalties and wage theft. Wage theft can take the form of denial of payments through the piece-rate system, physical and psychological abuse, coercion and threats.

The fundamental dehumanization of workers and dangerous violations to basic human rights like access to drinking water and safe working conditions were noted by workers in the first study of the Michigan Farmworker Project, conducted from 2019 to 2021.

These quotes represent the voices of female and male farmworkers captured in the research. Names are not included to comply with privacy laws and federal research regulations.

“You have to make at least a thousand pounds per week, and if you do not, they cannot be paying you per hour (referring to minimum wage). They only give you three weeks (in the workplace). If you did not make it (to reach minimum wage) in the piece-rate system, they fire you.”

“We were very thirsty and (the grower) did not give us water and I left my line, I went to drink water and the grower looked at me very upset and asked why did you leave the line and I told him ‘you know that it is very hot, I feel dizzy, I need to drink water.’”

“(The grower) wanted me to stay working in the blueberry machine. I suffer from epilepsy and I also have a heart condition, so I cannot get agitated. My husband told him that I already worked and that we could leave it for tomorrow. The grower got very upset and said ‘I am not going to have people that do not want to work with me. Why don’t you just leave the house tonight?’ My son was only 10 months old, where were we going to go? We do not have anywhere else to go and not only that he was very racist. He mistreated (people), he did not have water for my husband and the other worker and he did not want them to take their lunch break and he did not want to pay us.”

When farmworkers are dehumanized and treated as disposable labor, their agency and human rights are stripped away. This not only deepens health inequities but also undermines the core American principles of liberty, equality and justice for all.

Dr. Iglesias-Rios is supported by a research supplement provided by grant P30ES017885 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health and the Anti-Racism Research & Community Impact Faculty grant, National Center for Institutional Diversity (NCID) , University of Michigan. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors. It does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the CDC, or the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services.

Alexis J. Handal receives funding from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), National Institutes of Health, and from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Read These Next

When civil rights protesters are killed, some deaths – generally those of white people – resonate mo

From the civil rights era of the 1960s until today, white victims of government violence have received…

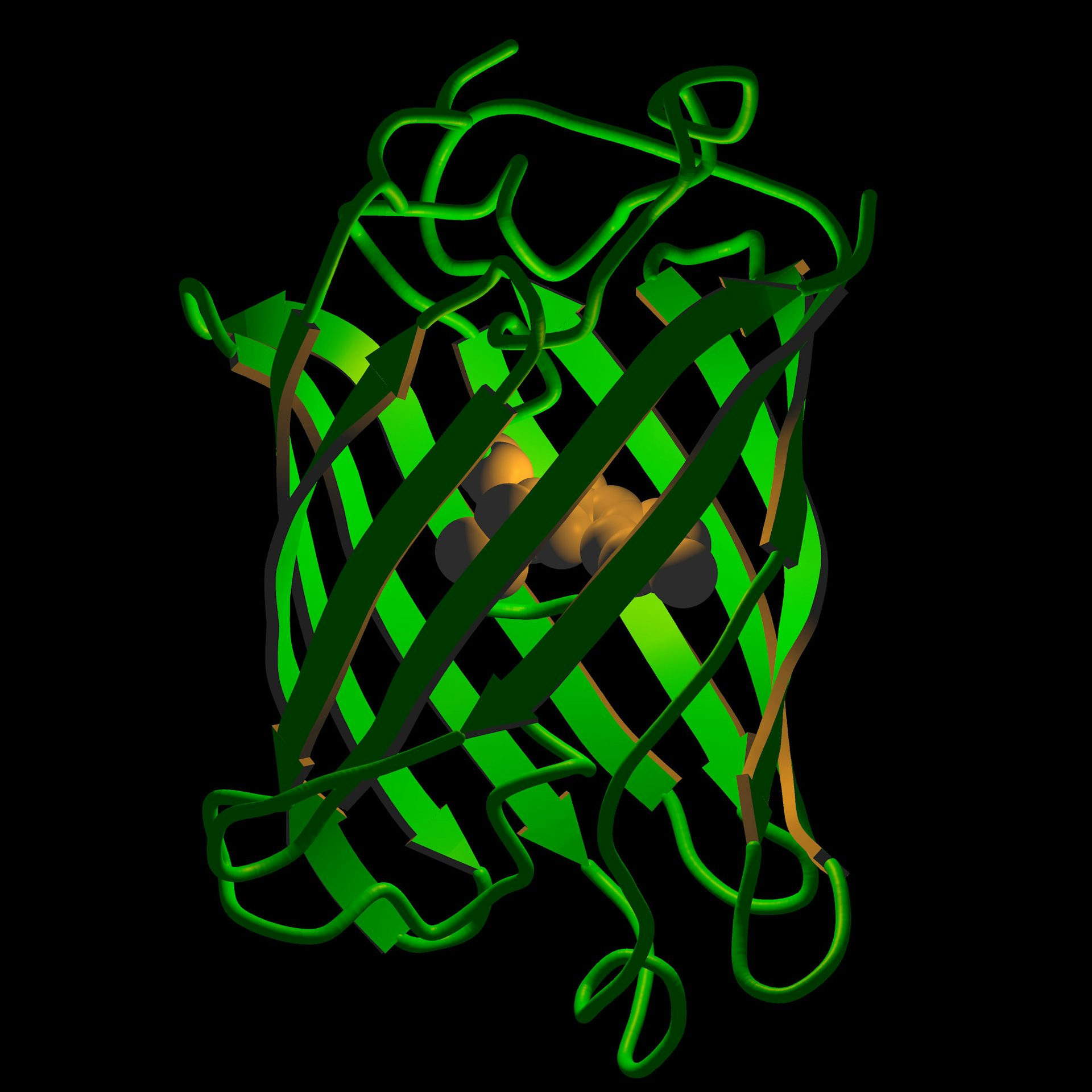

1 protein to rule them all – why crowning the protein that makes jellyfish glow green as a model can

Researchers have been studying tens of thousands of proteins and even more variations without a yardstick…

Supreme Court’s Michigan pipeline case is about Native rights and fossil fuels, not just technical l

The issue in front of the US Supreme Court is seemingly mundane, about federal or state jurisdiction.…