Amazon dives into groceries with Whole Foods: Five questions answered

Amazon paid a premium to snap up the upscale grocery chain, so we asked an economist to help us better understand the deal and what it means.

Editor’s note: Amazon became a major player in the supermarket business overnight after the online retailer said it was buying upscale grocery chain Whole Foods for US$13.7 billion, including debt, a premium of 27 percent over Whole Foods’ presale share price. The purchase would be Amazon’s biggest ever. We asked economist Roger Meiners to explain what Amazon gets out of it and why Whole Foods agreed to sell.

Why would Amazon pay so much for bricks and mortar?

Buying Whole Foods gives Amazon 465 premier locations immediately. Whole Foods will continue to sell food, but as an Amazon subsidiary there is a chance to experiment with other facets of Amazon’s retailing experience. In other words, Amazon sees more than just a grocery subsidiary in Whole Foods.

Amazon has already been experimenting on its own with, for example, Amazon Go, which opened in its hometown of Seattle as a beta program for the company’s employees. Shoppers must use the Amazon Go app, which features “just walk out” technology that automatically detects all the products they’ve taken off the shelves. Amazon then simply charges their account for whatever items they leave with.

So with Whole Foods, Amazon could try this with prepared foods. Busy people could walk in on their lunch break, pick up what they want and walk out without having to wait in a checkout line. And now Amazon can do this on a much larger scale and won’t have to build a network of stores from scratch.

In addition, Whole Foods has a strong brand and above-average income clientele willing to pay a premium for groceries – and perhaps much else. After all, its nickname isn’t “whole paycheck” for nothing.

Is there a risk that increased automation will lead to job losses at Whole Foods, an issue facing the entire economy in coming years as more tasks are replaced by robots? I don’t think this is a big risk for Whole Foods. There’s only so much automation can do in the grocery business. The company will still need people to prepare the meals, for example, even if it won’t need as many cashiers.

Food delivery has failed before, so why does Amazon think it might work now?

Food delivery was tried before, back in the dot-com era in the late 1990s.

The promise was that everything was going to be ordered online and delivered, including groceries. As you may remember from that era’s bubble bursting, it did not work all that well back then.

One problem for delivered foods in particular is that people worry that they will be given lower-quality fruits and vegetables. When we go to the store, we can choose what we like and pick only high-quality produce. Seeing the Whole Foods brand on the grocery bag likely reduces this concern, which may encourage online grocery orders.

And another element of success is the physical locations themselves, something that has helped grocery delivery service Peapod expand in recent years. Amazon may see that as a model for Whole Foods.

What other benefits might Amazon obtain?

Whole Foods’ physical stores could also allow Amazon to reduce reliance on UPS and other delivery services.

As it is now, Amazon Prime customers like me can order some cheap trinket and have it delivered “free” by UPS within two days. Yet sometimes the goods cost less than what Amazon pays for shipping, and that’s a large cost the retailer would like to reduce.

Thus Whole Foods stores could give Amazon a new delivery outlet to cut these costs. For example, as an alternative to home delivery, Amazon could allow customers to pick up their package at the nearest Whole Foods and earn bonus points or some other reward for helping the retailer reduce its shipping costs.

As most of us go grocery shopping a lot more than we shop for clothing, the attractiveness of picking up deliveries at Whole Foods stores seems clear.

As does the attractiveness of Amazon’s purchase, which clearly wasn’t about quantity. If it had been, Amazon might have purchased children’s clothing chain Gymboree, which just filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, with its 1,281 stores (it plans to close as many as 450 of them).

Rather, Amazon wanted a high-end grocery chain with convenient parking to provide a more attractive locale for foot traffic to pick up orders.

Should we be concerned that Amazon will have a monopoly on the economy along with Google and Apple?

These companies, which were modest a decade ago, are now among the largest organizations in the world. There is concern – fueled in part by purchases like this one – that they will control too much as the tech companies take over the world.

That, in my opinion, is an old saw. We have heard the scaremongers throughout history. Remember when IBM was the dominant company in the computer market? It is just part of the evolution of business that goes back to economist Joseph Schumpeter’s idea of creative destruction.

Old grocery stores may fall by the wayside as people choose new modes of delivery for goods they want. But Amazon, with Whole Foods, isn’t alone in going this way. Other companies are experimenting in these areas as well, such as Walmart, and smaller, nimbler businesses like Peapod will always be nipping at the giants’ heels. Or these giants may become dinosaurs and unable to react to new conditions. No company stays dominant forever.

Why would Whole Foods sell itself?

Whole Foods CEO and co-founder John Mackey had recently been fending off a serious threat from investors who wanted to force a sale of the chain or a big boardroom shakeup, including his ouster. While he had been publicly resisting their efforts, it’s hard to know if he was just sick of fighting or not.

But in the end, Mackey negotiated a premium sale price and gets to keep his job as CEO of his “baby” as part of one of the most valued and innovative companies in the world. That must offer some personal satisfaction.

And while he may think he’s taking Whole Foods into the future of retail, he may also be taking it back in time, to the bygone era of general stores, where you could get just about anything. In some locales, it even served as the post office too – it’s almost like a template for the virtual general store Amazon has become.

Whole Foods may bring this concept back to actual brick and mortar. In old westerns, there was always a general store where you could get crackers and a lasso. The same might be true about the new incarnation of Whole Foods. You could stop in to get organic crackers and pick up the exercise rope you ordered from Amazon.

Roger Meiners does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Read These Next

GLP-1 drugs may fight addiction across every major substance, according to a study of 600,000 people

GLP-1 drugs are the first medication to show promise for treating addiction to a wide range of substances.

Trauma patients recover faster when medical teams know each other well, new study finds

A new study from a Pittsburgh hospital finds that trauma patients recover faster when emergency medical…

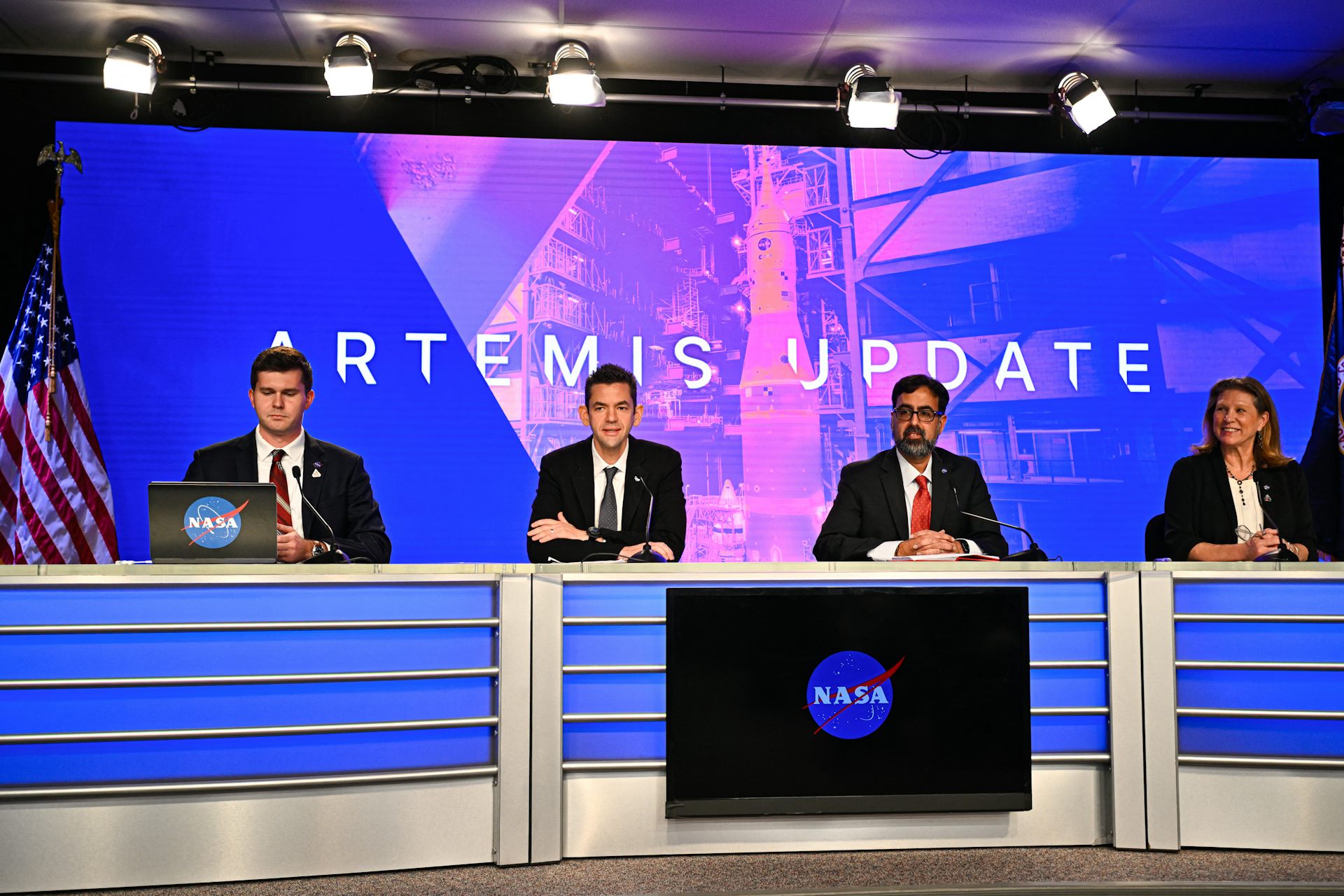

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…