Building subsidized low-income housing actually lifts property values in a neighborhood, contradicti

The concentration of subsidized low-income housing developments isn’t as bad as residents fear: It actually increases property values – at a faster rate than other neighborhoods.

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

Building multiple publicly subsidized low-income housing developments in a neighborhood doesn’t lower the value of other homes in the area – and in fact can even increase their worth, according to a new peer-reviewed study I co-authored.

For the study, we looked at 508 developments financed through the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program and built in the Chicago area from 1997 to 2016. We then examined their influence on more than 600,000 nearby residential sales, using data from local property assessments and tax records. We chose Chicago because of its size, well-established neighborhoods, substantial amount of subsidized housing developments, well-documented racial and ethnic segregation, pockets of persistent and concentrated poverty and excellent data coverage. While some readers may have pictures of dilapidated buildings in their minds, the projects we looked at were generally well built and well maintained.

We found that, relative to comparable homes in other neighborhoods, average home prices jumped by 10% within a quarter-mile of the first affordable housing development that was built in a neighborhood and 2% within a quarter-mile over a 15-year period or through 2016. To ensure we were isolating the effect of the low-income housing program, we also looked at preexisting market trends to make sure neighborhoods that showed the faster price growth weren’t already growing at a faster rate before the low-income housing.

What was more striking to us, however, is that additional developments in the same area generally further increased housing prices. Building two more developments increased prices by a total of 3 additional percentage points, on average, within a quarter-mile and 4 percentage points over the next quarter-mile. In other words, a neighborhood within a quarter-mile of all three developments saw gains of 13% on average over the period.

These additional effects are important because low-income housing projects are disproportionately concentrated geographically, especially in lower-income areas.

We also found that these effects occurred regardless of whether it was a low- or high-income neighborhood and no matter its racial composition.

While other studies have previously shown Low-Income Housing Tax Credit developments typically have positive effects on surrounding property values, ours was the first to look at the impact of several projects in one neighborhood.

Why it matters

Homeowners are often worried that the development of publicly subsidized housing in their neighborhoods will lower the value of their homes.

The primary concerns seem to be that such housing developments will lead to higher levels of crime and poverty, as well as requiring wealthier residents to pay higher costs for services and education, according to a 2012 study of “not in my back yard,” or NYMBY, opposition. These concerns are particularly acute when multiple projects are clustered closely together, reminding many Americans of public housing projects that concentrated poverty and crime in the mid-20th century.

But today’s affordable housing developments are different than those of the past, which were often cheaply built and poorly maintained. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program supports private developers who have an incentive to build high-quality buildings and implement good property management.

Although local homeowners often oppose these buildings, our results show that they are less cause for concern than people may think.

What still isn’t known

We didn’t measure the effects of the new developments on area rental prices, so we don’t know how the subsidized rental units affected rents in unsubsidized properties nearby. That is a subject for future research. Similarly, while we demonstrated statistically that the developments themselves catalyzed the positive changes in values, we did not examine which particular aspects of the developments were the primary drivers of that change.

What’s next

We’re currently finishing up our follow-up study in Los Angeles – another large city but with very different dynamics from Chicago’s. Our findings, which are currently undergoing peer review, show markedly similar effects, though we found the biggest gains in property values after multiple projects in a neighborhood.

We also are examining whether the observed property value effects differ when factoring in the size of the building, the presence of market-rate units and the type of developer.

Sean Zielenbach, president of SZ Consulting and a co-author of the study, contributed to this article.

This research was funded in part by a generous grant from the JPMorgan Chase Foundation to Enterprise Community Partners, and we gratefully acknowledge their support, as well as the University of Southern California’s Bedrosian Center on Governance and the Public Enterprise. The funders played no role in the research itself.

Read These Next

Public defender shortage is leading to hundreds of criminal cases being dismissed

There are never enough lawyers to provide indigent defense, but the situation has gotten worse since…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

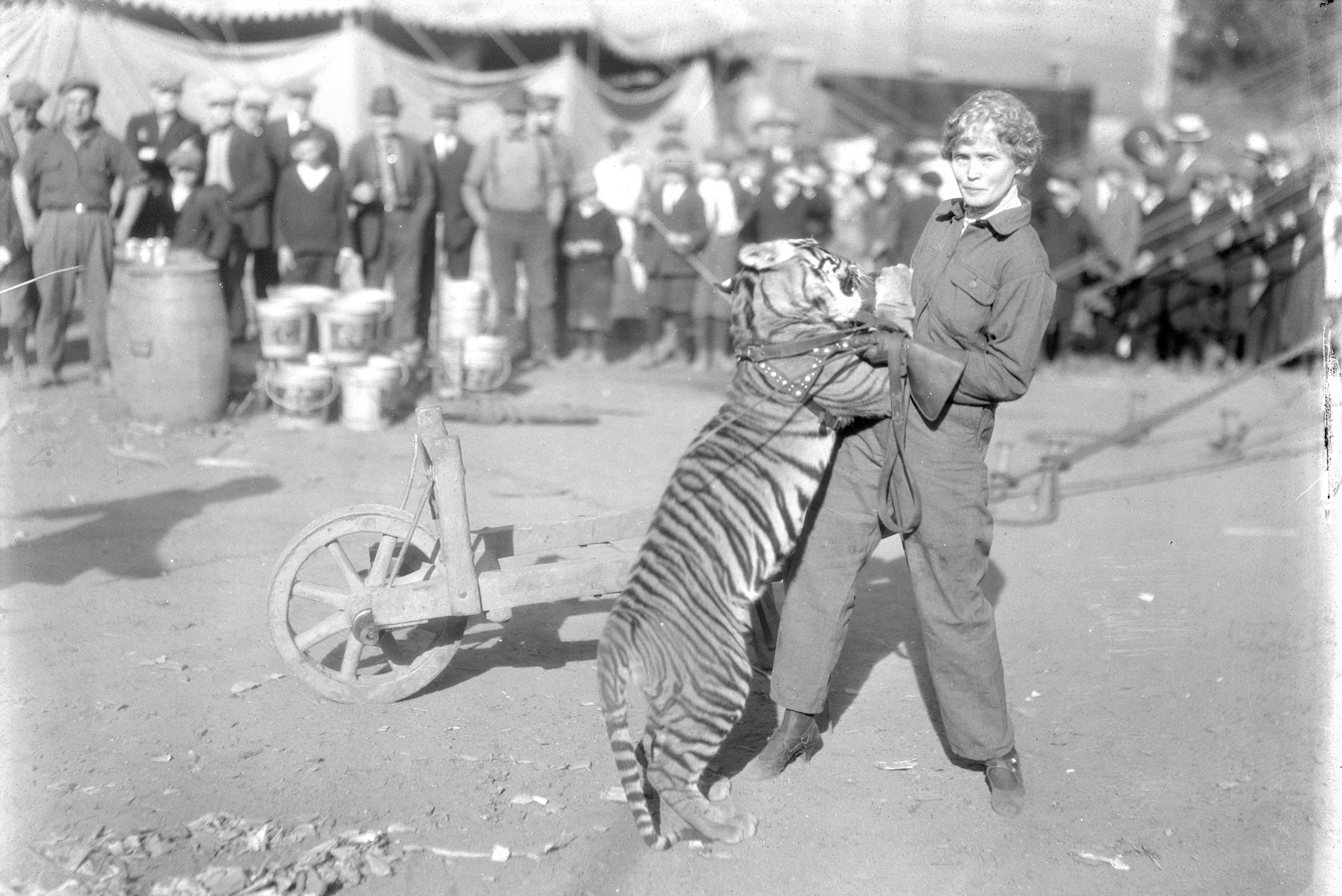

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.