How Mary Kay contributed to feminism – even though she loathed feminists

Ash derided women’s liberation as “that foolishness” – but her success story is very feminist.

In 1963, the same year American businesswoman Mary Kay Ash started her cosmetics company, publisher W.W. Norton released “The Feminine Mystique – the book that has since been widely credited with launching the contemporary women’s liberation movement.

Ash loathed the term "feminist” and disliked the movement. In a 1983 Dallas Morning News interview, she dismissed “that foolishness feminists started in the ‘60s” of “trying to act just like a man” by cutting their hair short or lowering their voices.

Yet Ash, who died in 2001, successfully defied her era’s female gender norms. She turned a few thousand dollars into a multibillion-dollar cosmetics empire and led it for decades. Her sales force grew from fewer than 10 women to tens of thousands.

While researching a book on Ash’s life and work, I’ve learned that many of the Mary Kay saleswomen were comfortable with their era’s vision of femininity and motherhood. Ash’s company motto of “God First, Family Second, Career Third” put them at ease.

American women today owe gratitude to the women’s movement of the 1960s for making issues like equal pay for equal work and sharing household responsibilities part of the national conversation – but also to a Dallas entrepreneur who reveled in the feminine mystique.

From underpaid saleswoman to CEO

In 1963, the year Ash founded “Beauty by Mary Kay” in a small Dallas storefront, barely a third of American women were in the workforce. Ash was one of them. She had peddled children’s encyclopedias door to door, and conducted “house parties” - home demonstrations of products that catered to housewives – with Stanley Home Goods and other companies.

Ash consistently earned lower wages than her male counterparts, who also passed her by for promotions. When she protested, one common response was to deride her for “thinking like a woman.” Another was that men needed more money because they had families to support.

“I had a family to support too!” recalled Ash, a single mother, in her 1981 memoir. So she quit to build a company where there would be no wage gap or male bosses, and women would be rewarded for thinking like women – all while embracing the vision of traditional gender roles that the feminist movement was trying to overturn.

By 1969, the company was earning US$6.3 million in net sales, according to The New York Times. And an article in the Irving Daily News, a Texas newspaper, put the sales force at around 4,000 women from 15 different states.

In 1976, Mary Kay Inc. became the first woman-founded and -led company listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

In 1979, glowing coverage on “60 Minutes” prompted nearly 100,000 more women to sign up. The company was grossing over $100 million annually and had a global reach, and Ash was named one of the year’s top corporate women in America by Business Week magazine.

In 1985 Ash and her son led a $450 millon deal to buy the company back into private family hands. As of 2021, the company reportedly has $3.5 billion in annual revenues.

The Mary Kay mystique

Ash rejected feminism but sought to build women’s confidence – something absent in the average housewife’s life, according to “The Feminine Mystique” – as well as their income.

“Here’s a woman who’s never had any praise at all for anything she’s ever done,” Ash said in her best-selling memoir. “Maybe the only applause she’s ever had was when she graduated from high school. So we praise her for everything good that she does.”

Based on the interviews I’m doing for my research, this approach worked.

Esther Andrews, a housewife, told me that before she became a Mary Kay saleswoman in 1967, “nobody had ever said that I could be great at anything.” Andrews, who raised three children with her Mary Kay earnings after her husband died, was among the first winners of a pink Cadillac – a company prize for top sellers. The car was both a symbol of her success and a means of mobility few housewives enjoyed at the time.

Andrews’ story reflects that of many I’ve uncovered. From a former waitress and single mom in New Jersey who was able to raise her daughter and purchase her own home to a former housewife in Ohio who has more diamond rings than fingers and funds her family’s European vacations, Mary Kay has changed women’s lives.

Both of these women fought back tears as they shared their career accomplishments with me. Both have been in the company for more than 30 years.

In her book “In Pink: The Personal Story of a Mary Kay Pioneer Who Made History Shaping a New Path to Success for Women,” homemaker and early Mary Kay recruit Doretha Dingler remarked that “much more than raising our family income, that kind of earning raised my consciousness” – language echoing that of the era’s feminists.

Opportunities for women of color

It wasn’t just middle-class white women who found success in Mary Kay.

In 1975, Ruell Cone, a Black woman from Atlanta, was the company’s highest-earning saleswoman. She was honored in person by Ash herself before tens of thousands of saleswomen at the company’s annual seminar.

In 1979, Gerri Nicholson told The Record newspaper of Hackensack, N.J., that while she had “a lot of hang-ups” from growing up as an African American in the South, working for Mary Kay “substantially increased my family income” and gave her “a feeling of self-worth.” At that point Nicholson had worked her way up from saleswoman to sales manager, and would go on to become Mary Kay’s first Black national sales director.

By 1985, Savvy magazine reported that Mary Kay Inc. could claim more Latina and Black women earning annual commissions of over $50,000 – the equivalent of $137,000 in 2022 – than any other corporation worldwide.

Ash’s elevation of “thinking like a woman” and the company’s acceptance of Black and Latina saleswomen are also forerunners of feminism’s “third wave” in the 1990s. In this era, younger feminists shifted the movement’s focus from equal rights to diversity, embracing gender differences and celebrating femininity in its various forms.

A ‘pink pyramid scheme’?

Along with these success stories, the company has faced accusations of exploiting more women than it enriches. A 2012 article in Harper’s Magazine, “The Pink Pyramid Scheme,” pointed at unrealized promises of success, saleswomen going into debt to purchase product inventory, and high turnover rates.

I believe these stories are a part of any accurate telling of Mary Kay history.

However, based on my research, a substantial number of the company’s “beauty consultants” say they found camaraderie, recognition and confidence working for Mary Kay, and a female role model in Mary Kay Ash.

These are things working women today still find elusive.

Cassandra L. Yacovazzi ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

Read These Next

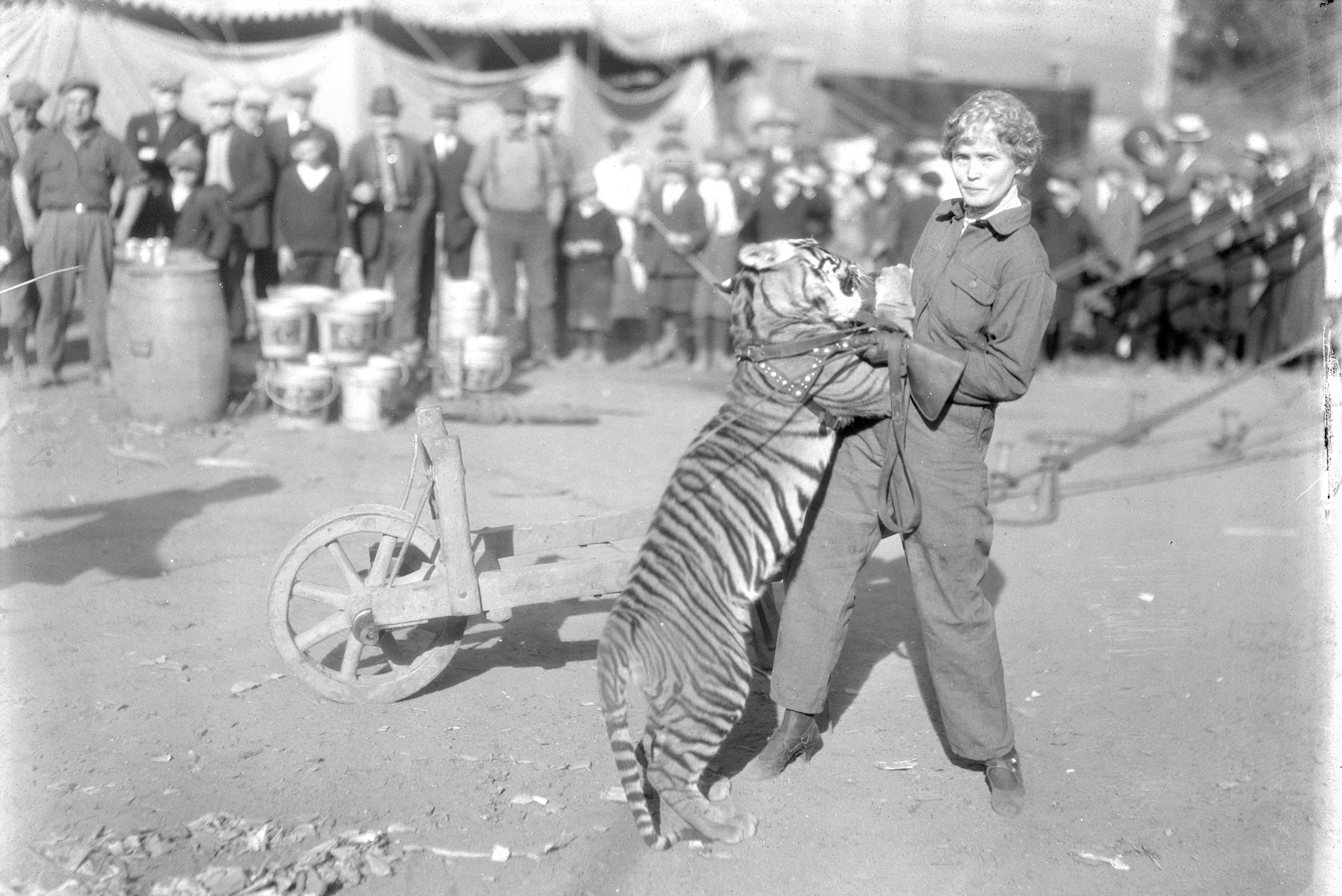

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

The apocrypha, Christianity’s ‘hidden’ texts, may not be in the Bible – but they have shaped traditi

‘Apocrypha’ means ‘hidden’ in Greek, but it is often used to describe texts that are outside…