A case for retreat in the age of fire

Communities already retreat from flooding and in the face of sea level rise. Is retreat from wildfires next, and what would that look like?

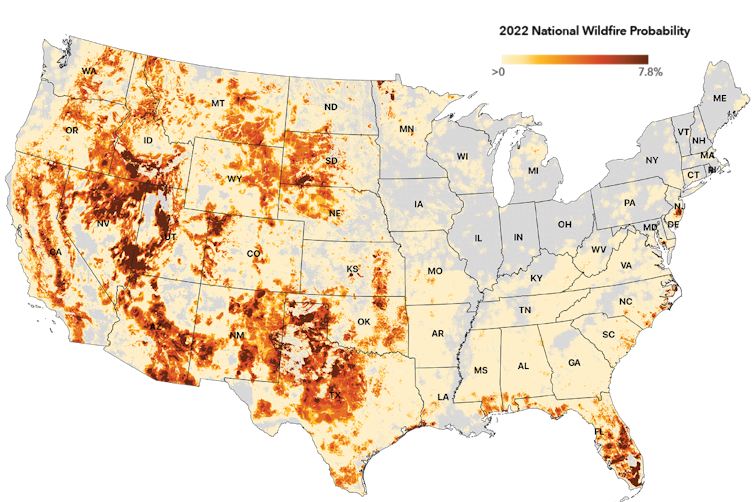

Wildfires in the American West are getting larger, more frequent and more severe. Although efforts are underway to create fire-adapted communities, it’s important to realize that we cannot simply design our way out of wildfire – some communities will need to begin planning a retreat.

Paradise, California, is an example. For decades, this community has worked to reduce dry grasses, brush and forest overgrowth in the surrounding wildlands that could burn. It built firebreaks to prevent fires from spreading, and promoted defensible space around homes.

But in 2018, these efforts were not enough. The Camp Fire started from wind-damaged power lines, swept up the ravine and destroyed over 18,800 structures. Eighty-five people died.

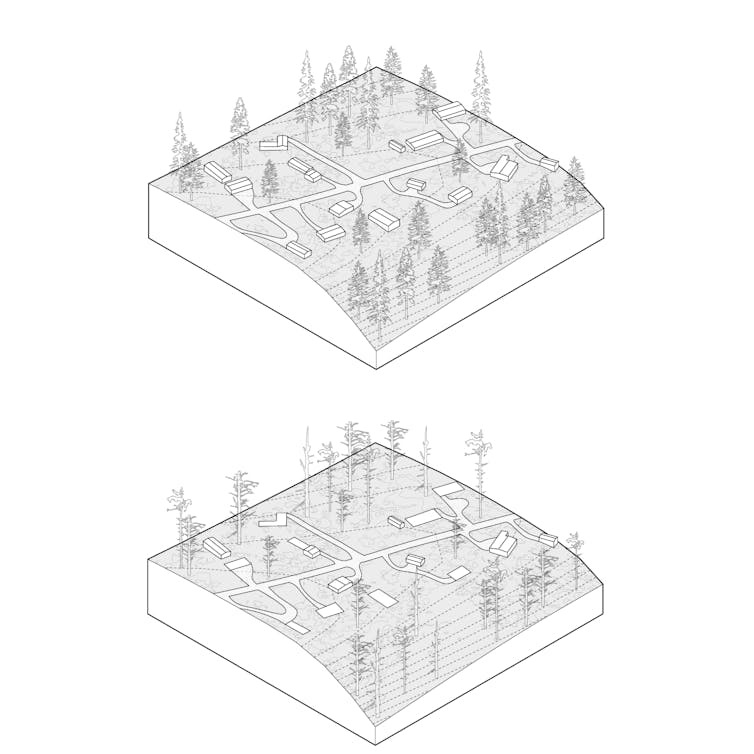

Across the America West, thousands of communities like Paradise are at risk. Many, if not most, are in the wildland-urban interface, a zone between undeveloped land and urban areas where both wildfires and unchecked growth are common. From 1990 to 2010, new housing in the wildland-urban interface in the continental U.S. grew by 41%.

Whether in the form of large, master-planned communities or incremental, house-by-house construction, developers have been placing new homes in danger zones.

It has been nearly four years since the Camp Fire, but the population of Paradise is now less than 30% of what it once was. This makes Paradise one of the first documented cases of voluntary retreat in the face of wildfire risk. And while the notion of wildfire retreat is controversial, politically fraught and not yet endorsed by the general public, as experts in urban planning and environmental design, we believe the necessity for retreat will become increasingly unavoidable.

But retreat isn’t only about wholesale moving. Here are four forms of retreat being used to keep people out of harm’s way.

Limiting future development

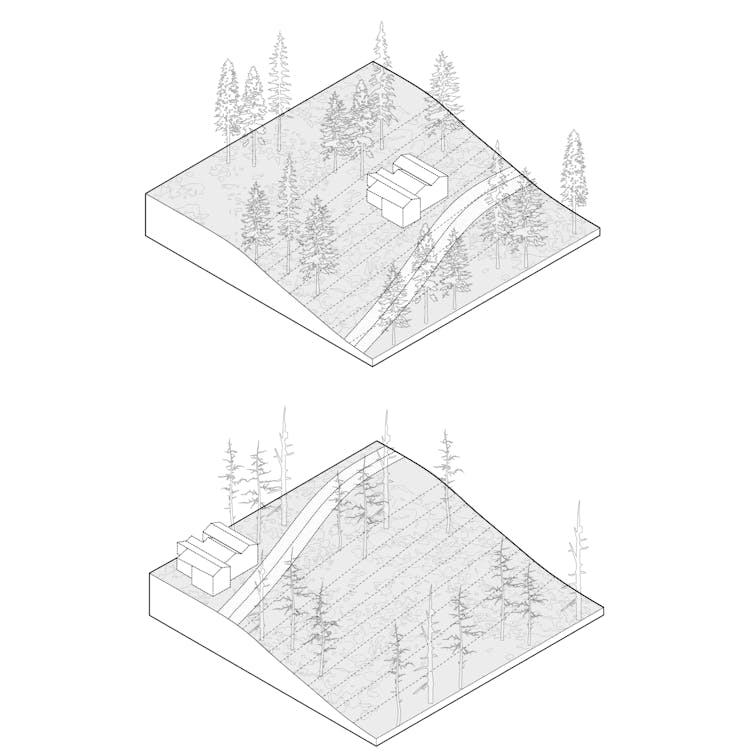

On one end of the wildfire retreat spectrum are development-limiting policies that create stricter standards for new construction. These might be employed in moderate-risk areas or communities disinclined to change.

An example is San Diego’s steep hillside guidelines that restrict construction in areas with significant grade change, as wildfires burn faster uphill. In the guidelines, steep hillsides have a gradient of at least 25% and a vertical elevation of at least 50 feet. In most cases, new buildings cannot encroach into this zone and must be located at least 30 feet from the hillside.

While development-limiting policies like this prevent new construction in some of the most hazardous conditions, they often cannot eliminate fire risk.

Halting new construction

Further along the spectrum are construction-halting measures, which prevent new construction to manage growth in high-risk parts of the wildland-urban interface.

These first two levels of action could both be implemented using basic urban planning tools, starting with county and city general plans and zoning, and subdivision ordinances. For example, Los Angeles County recently updated its general plan to limit new sprawl in wildfire hazard zones. Urban growth boundaries could also be adopted locally, as many suburban communities north of San Francisco have done, or could be mandated by states, as Oregon did in 1973.

To assist the process, states and the federal government could designate fire-risk areas, similar to Federal Emergency Management Agency flood maps. California already designates zones with three levels of fire risk: moderate, high and very high.

They could also develop fire-prone landscape zoning acts, similar to legislation that has helped limit new development along coasts, on wetlands and along earthquake faults.

Incentives for local governments to adopt these frameworks could be provided through planning and technical assistance grants or preference for infrastructure funding. At the same time, states or federal agencies could refuse funding for local authorities that enable development in severe-risk areas.

In some cases, state officials might turn to the courts to stop county-approved projects to prevent loss of life and property and reduce the costs that taxpayers might pay to maintain and protect at-risk properties

Threehigh-profile projects in California’s wildland-urban interface have been stopped in the courts because their environmental impact reports fail to adequately address the increased wildfire risk that the projects create. (Full disclosure: For a short time in 2018, one of us, Emily Schlickman, worked as a design consultant on one of these – an experience that inspired this article.)

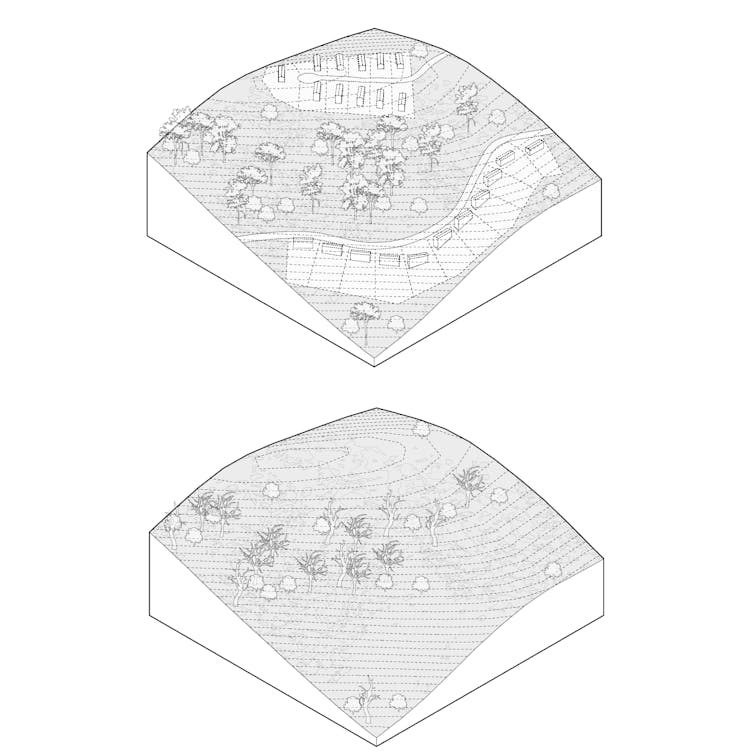

Incentives to encourage people to relocate

In severe risk areas, the technique of “incentivized relocating” could be tested to help people move out of wildfire’s way through programs such as voluntary buyouts. Similar programs have been used after floods.

Local governments would work with FEMA to offer eligible homeowners the pre-disaster value of their home in exchange for not rebuilding. To date, this type of federally backed buyout program has yet to be implemented for wildfire areas, but some vulnerable communities have developed their own.

The city of Paradise created a buyout program funded with nonprofit grant money and donations. However, only 300 acres of patchworked parcels have been acquired, suggesting that stronger incentives and more funding may be required.

Removing government-backed fire insurance plans or instituting variable fire insurance rates based on risk could also encourage people to avoid high-risk areas.

Another potential tool is a “transferable development rights” framework. Under such a framework, developers wishing to build more intensively in lower-risk town centers could purchase development rights from landowners in rural areas where fire-prone land is to be preserved or returned to unbuilt status. The rural landowners are thus compensated for the lost use of their property. These frameworks have been used for growth management purposes in Montgomery County, Maryland, and in Massachusetts and Colorado.

Moving entire communities, wholesale

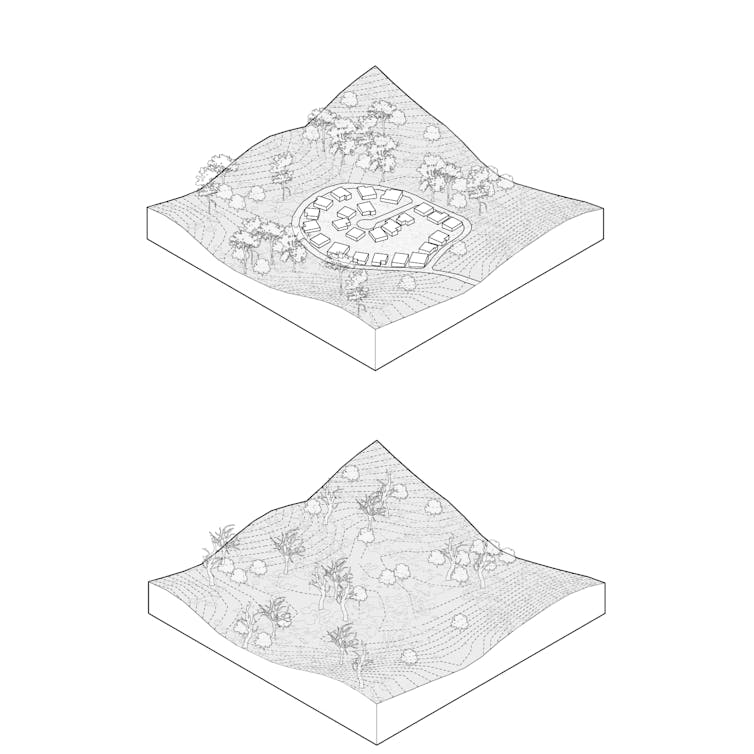

Vulnerable communities may want to relocate but don’t want to leave neighbors and friends. “Wholesale moving” involves managing the entire resettlement of a vulnerable community.

While this technique has yet to be implemented for wildfire-prone areas, there is a long history of its use after catastrophic floods. One place it is currently being used is Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, which has lost 98% of its landmass since 1955 because of erosion and sea level rise. In 2016, the community received a federal grant to plan a retreat to higher ground, including the design of a new community center 40 miles north and upland of the island.

This technique, though, has drawbacks – from the complicated logistics and support needed to move an entire community to the time frame needed to develop a resettlement plan to potentially overloading existing communities with those displaced.

Even with ideal landscape management, wildfire risks to communities will continue to increase, and retreat from the wildland-urban interface will become increasingly necessary. The primary question is whether that retreat will be planned, safe and equitable, or delayed, forced and catastrophic.

Emily Schlickman previously worked as a design consultant on Guenoc Valley Resort, a project referenced in the article.

Brett Milligan and Stephen M. Wheeler do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…

Former Harvard president Summers’ soft landing after Epstein revelations is case study of economics’

Despite repeated calls for the university to revoke his tenure, the economist held onto his teaching…