Climate change is an infrastructure problem – map of electric vehicle chargers shows one reason why

The infrastructure bill being debated in Congress looks like a small but genuine down payment on a more climate-friendly transportation sector and electric power grid. What comes next is crucial.

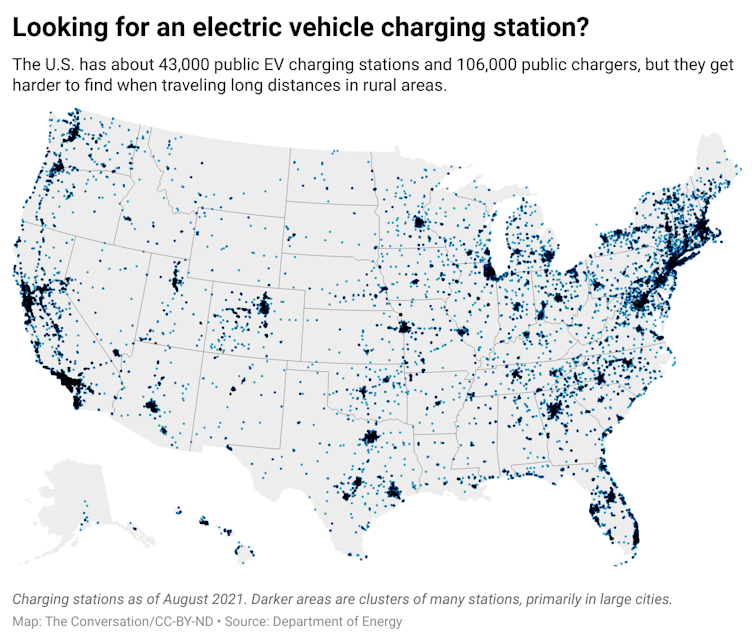

Most of America’s 107,000 gas stations can fill several cars every five or 10 minutes at multiple pumps. Not so for electric vehicle chargers – at least not yet. Today the U.S. has around 43,000 public EV charging stations, with about 106,000 outlets. Each outlet can charge only one vehicle at a time, and even fast-charging outlets take an hour to provide 180-240 miles’ worth of charge; most take much longer.

The existing network is acceptable for many purposes. But chargers are very unevenly distributed; almost a third of all outlets are in California. This makes EVs problematic for long trips, like the 550 miles of sparsely populated desert highway between Reno and Salt Lake City. “Range anxiety” about longer trips is one reason electric vehicles still make up fewer than 1% of U.S. passenger cars and trucks.

This uneven, limited charging infrastructure is one major roadblock to rapid electrification of the U.S. vehicle fleet, considered crucial to reducing the greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change.

It’s also a clear example of how climate change is an infrastructure problem – my specialty as a historian of climate science at Stanford University and editor of the book series “Infrastructures.”

Over many decades, the U.S. has built systems of transportation, heating, cooling, manufacturing and agriculture that rely primarily on fossil fuels. The greenhouse gas emissions those fossil fuels release when burned have raised global temperature by about 1.1°C (2°F), with serious consequences for human lives and livelihoods, as the recent report from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change demonstrates.

The new assessment, like its predecessor Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, shows that minimizing future climate change and its most damaging impacts will require transitioning quickly away from fossil fuels and moving instead to renewable, sustainable energy sources such as wind, solar and tidal power.

That means reimagining how people use energy: how they travel, what and where they build, how they manufacture goods and how they grow food.

Gas stations were transport infrastructure, too

Gas-powered vehicles with internal combustion engines have completely dominated American road transportation for 120 years. That’s a long time for path dependence to set in, as America built out a nationwide system to support vehicles powered by fossil fuels.

Gas stations are only the endpoints of that enormous system, which also comprises oil wells, pipelines, tankers, refineries and tank trucks – an energy production and distribution infrastructure in its own right that also supplies manufacturing, agriculture, heating oil, shipping, air travel and electric power generation.

Without it, your average gas-powered sedan wouldn’t make it from Reno to Salt Lake City either.

Fossil fuel combustion in the transport sector is now America’s largest single source of the greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change. Converting to electric vehicles could reduce those emissions quite a bit. A recent life cycle study found that in the U.S., a 2021 battery EV – charged from today’s power grid – creates only about one-third as much greenhouse gas emissions as a similar 2021 gasoline-powered car. Those emissions will fall even further as more electricity comes from renewable sources.

Despite higher upfront costs, today’s EVs are actually less expensive than gas-powered cars due to their greater energy efficiency and many fewer moving parts. An EV owner can expect to save US$6,000-$10,000 over the car’s lifetime versus a comparable conventional car. Large companies including UPS, FedEx, Amazon and Walmart are already switching to electric delivery vehicles to save money on fuel and maintenance.

All this will be good news for the climate – but only if the electricity to power EVs comes from low-carbon sources such as solar, tidal, geothermal and wind. (Nuclear is also low-carbon, but expensive and politically problematic.) Since our current power grid relies on fossil fuels for about 60% of its generating capacity, that’s a tall order.

To achieve maximal climate benefits, the electric grid won’t just have to supply all the cars that once used fossil fuels. Simultaneously, it will also need to meet rising demand from other fossil fuel switchovers, such as electric water heaters, heat pumps and stoves to replace the millions of similar appliances currently fueled by fossil natural gas.

The infrastructure bill

The 2020 Net-Zero America study from Princeton University estimates that engineering, building and supplying a low-carbon grid that could displace most fossil fuel uses would require an investment of around $600 billion by 2030.

The infrastructure bill now being debated in Congress was originally designed to get partway to that goal. It initially included $157 billion for EVs and $82 billion for power grid upgrades. In addition, $363 billion in clean energy tax credits would have supported low-carbon electric power sources, along with energy storage to provide backup power during periods of high demand or reduced output from renewables. During negotiations, however, the Senate dropped the clean energy credits altogether and slashed EV funding by over 90%.

Of the $15 billion that remains for electric vehicles, $2.5 billion would purchase electric school buses, while a proposed EV charging network of some 500,000 stations would get $7.5 billion – about half the amount needed, according to Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm.

As for the power grid, the infrastructure bill does include about $27 billion in direct funding and loans to improve grid reliability and climate resilience. It would also create a Grid Development Authority under the U.S. Department of Energy, charged with developing a national grid capable of moving renewable energy throughout the country.

The infrastructure bill may be further modified by the House before it reaches President Joe Biden’s desk, but many of the elements that were dropped have been added to another bill that’s headed for the House: the $3.5 trillion budget plan.

As agreed to by Senate Democrats, that plan incorporates many of the Biden administration’s climate proposals, including tax credits for solar, wind and electric vehicles; a carbon tax on imports; and requirements for utilities to increase the amount of renewables in their energy mix. Senators can approve the budget by simple majority vote during “reconciliation,” though by then it will almost certainly have been trimmed again.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Overall, the bipartisan infrastructure bill looks like a small but genuine down payment on a more climate-friendly transport sector and electric power grid, all of which will take years to build out.

But to claim global leadership in avoiding the worst potential effects of climate change, the U.S. will need at least the much larger commitment promised in the Democrats’ budget plan.

Like an electric car, that commitment will seem expensive upfront. But as the recent IPCC report reminds us, over the long term, the potential savings from avoided climate risks like droughts, floods, wildfires, deadly heat waves and sea level rise would be far, far larger.

Paul N. Edwards is one of 234 Lead Authors of the 2021 Working Group I report for the Sixth Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. This article reflects his personal views. His previous work relevant to this article was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Sloan Foundation.

Read These Next

Iraq war’s aftermath was a disaster for the US – the Iran war is headed in the same direction

More than 20 years after the US military success in Iraq, the outcome of the US effort at regime change…

Alaska’s glacial lakes are expanding, increasing the risk of destructive outburst floods

Scientists mapped the evolution of 140 glacial lakes in Alaska and found a way to tell how much larger…

US is less prone to oil price shocks than in past decades

Oil prices affect the US economy differently than in past decades. Nowadays, the US is less reliant…