Economists: Biden's $1,400 COVID-19 checks may be great politics, but it's questionable economics

The $1.9 trillion package gets a lot of stuff right, but the direct payments are not among them, argue two economists.

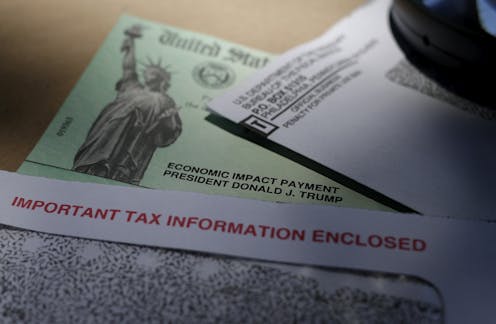

The US$1,400 direct checks to people are the most expensive and perhaps most popular part of the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package racing its way through Congress right now.

The House is set to vote on a final version of the package narrowly passed by the Senate on March 6 before it moves on to President Joe Biden’s desk for his signature. Moderate Senate Democrats, who had voiced concerns about how many people would receive direct payments in the original proposal endorsed by the House, managed to make them more targeted at lower-income households, which means an estimated 17 million fewer people will get a check.

The coronavirus package contains a lot of provisions that will help struggling Americans, and we understand why the checks are so popular – with 78% support among adults in a recent survey. No one turns down extra money, after all.

But as economists, we also believe that these direct payments make little economic sense – even with the lower income threshold. And this is true whether you think the purpose of the checks is relief or stimulus.

Relief needs to be targeted

First let’s consider the checks as relief.

The purpose of a measure primarily designed as relief during an economic crisis is to help those most affected.

The latest jobs report shows about 10 million people are unemployed, including 4.1 million who have been without a job for at least 27 weeks. That’s not to mention the millions more who have left the labor force altogether because of the pandemic. These people – mostly workers in the hospitality and leisure industries, disproportionately low-income and people of color – are in desperate need of aid and support, without which destitution and homelessness are real possibilities.

But for the vast majority of Americans, it’s like the pandemic never happened, financially speaking. These are mostly office workers and other professionals who have had to work from home for all or part of the pandemic but saw no change in their income. A recent Pew survey found that 79% of Americans reported their family’s financial situation is about the same as or better than a year ago.

The most pain was unsurprisingly among lower-income households, 31% of whom said they were worse off than a year ago – but even among this group over two-thirds said their situation was the same or better.

The House’s measure would have phased out completely at incomes of $100,000 for single people and $200,000 for couples. The Senate version phases out at $80,000 and $160,000, which would still benefit about 280 million people, including children, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a nonpartisan think tank.

This is a pretty marginal change and still means that checks will go to a lot of people who don’t really need them.

Stimulus needs to stimulate

OK, then how about the checks as a stimulus? So even if a lot of people who aren’t in desperate need get a payment, at least they’ll spend it and help the economy recover from the COVID-19 shock, right?

There are two problems with that. The first is that it’s not clear the economy needs much stimulus right now. While the jobs report showed millions of people remained unemployed, the February numbers came in a lot better than expected, adding to signs the U.S. economy is in fairly good shape. And there are also growing concerns about inflation, given the sharp rise in some market interest rates, which too much stimulus could accelerate.

The other issue is that past coronavirus checks haven’t been all that stimulative. The government began cutting $1,200 “economic impact” checks for most Americans back in March and sent out another round of checks about half that size in December.

Research conducted on the first round of checks found that the vast majority of Americans saved most of the money or used it to pay down debt. About 40% of the money went toward purchases supporting industries such as food, beauty and other nondurable consumer products that had already seen spikes in spending before the checks went out.

In other words, the checks weren’t very stimulative. Moreover, a third of likely recipients of the next round of checks said they would save the money.

A better use of the money

So you might be wondering, what’s a better way to spend the several hundred billion dollars earmarked for checks?

At a minimum, relief payments should be targeted, such as to people who lost jobs or are working fewer hours due to illness. But in our view, a better way would be to increase those supplemental unemployment checks from the $300 lawmakers agreed to to $600, as the first coronavirus relief measure included last March.

Or take the U.K. approach and provide targeted but generous income replacement for workers affected by COVID-19. Another very helpful and focused measure would be to help people pay for their mortgages and rent – otherwise a massive housing crisis is looming on the post-pandemic horizon.

We believe President Biden’s COVID-19 relief bill gets a lot right, such as significant aid to state and local governments, increased food stamp benefits and additional support for small businesses. Sending one-off $1,400 checks to people experiencing no economic hardship during the pandemic is not among them.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How a largely forgotten Supreme Court case can help prevent an executive branch takeover of federal

An FBI raid on a Georgia elections facility has sparked concern about Trump administration interference…

Do special election results spell doom for Republicans in 2026?

Special election results have anticipated recent midterm outcomes. With Democrats now overperforming,…

FDA rejects Moderna’s mRNA flu vaccine application - for reasons with no basis in the law

The move signals an escalation in the agency’s efforts to interfere with established procedures for…