Ancient Greek desire to resolve civil strife resonates today – but Athenian justice would be a 'bitt

Homer and Aeschylus turned to the divine to write their happy endings. But no gods are conspiring above the US, ready to swoop down and save humankind from itself.

America’s divisions are old. Politically and socially, they are rooted in grudges and ideological vengeance that goes back generations, to the New Deal era, when government vastly expanded its role in people’s lives. Economically and morally, the nation was founded on the sins of slavery and Indigenous genocide.

The consequences of this past are still present: The COVID-19 pandemic has been far harder on Native populations, Black communities and the poor.

Long-lasting civil strife isn’t new. Greek mythology, my field of academic scholarship, is rife with cycles of vengeance that threaten to obliterate society. Two of the most famous works of Greek literature, “The Odyssey” and the “Oresteia,” are stories of seemingly eternal divisions that end with opposing factions coming together.

In the anxiety of the postelection period, I am turning to these stories in hopes that the ancient Greeks have wisdom to share, as they have on plagues, mourning the dead and “alternative facts.”

How did the conflict-filled Greek society find its way forward?

Forgetting and forgiving?

One of the poems I looked to is Homer’s “Odyssey.” This epic poem, composed before the fifth century B.C., tells the story of a Trojan War veteran, Odysseus, whose return home takes 10 years. When his journey finally ends, he finds his wife, Penelope, besieged by suitors hoping to wed her and take over his position as ruler of the city of Ithaca.

Most people who read the “Odyssey” usually remember it as ending with the joyous reunion of Odysseus and Penelope, but the epic’s final book actually ends with bloodshed: Odysseus kills his wife’s suitors.

After the slaughter, their survivors gather to debate whether they should kill Odysseus in return. Slightly more than half the family members decide not to pursue vengeance, but the rest arm to face Odysseus.

Just as the sides are about to clash, Zeus sends the goddess Athena to stop them. She declares they should forget the slaughter, recognize Odysseus as king, and “let wealth and peace be enough.”

No one in this scene questions the ancient custom of vengeance; people expect that the murder of a loved one must be paid back with murder. The poem’s ending implies the only way to stop cyclical violence is for those on one side to simply forget how they’ve been wronged in exchange for the promise of peace and prosperity.

A split vote

The Greek playwright Aeschylus also recognizes vengeance as a human institution in “Eumenides,” the final play of his three-part “Oresteia” – but sees a different way to resolve it.

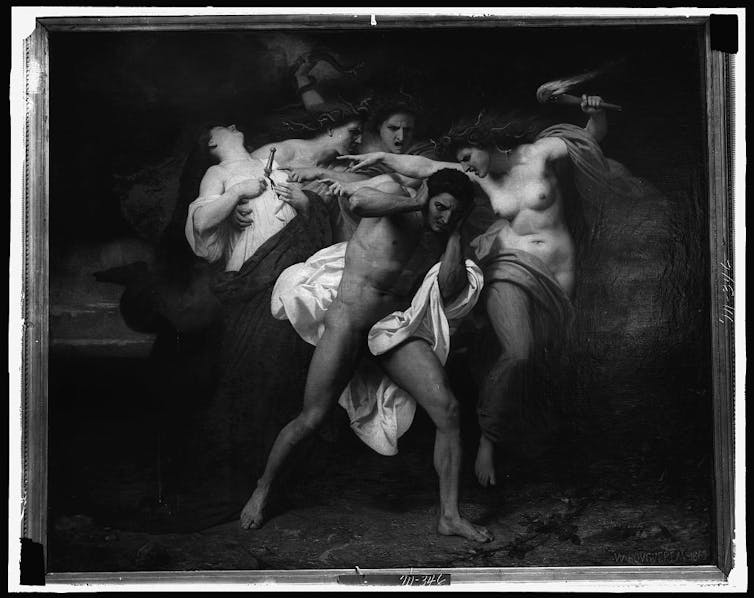

The “Oresteia” tells the story of Orestes, whose father, Agamemnon, returned home after the Trojan War and was murdered by his mother and her lover. The god Apollo orders Orestes to avenge his father’s death by killing his mother. He does this, but the Furies – earthbound goddesses of vengeance – curse him with madness for the murder. They pursue him until he takes sanctuary in Athens.

This is where Aeschylus’ “Eumenides” picks up Orestes’ story. In Athens, in an effort to resolve this cycle of vengeance, Athena establishes a trial by jury. After both the Furies and Apollo make their cases about whether or not Orestes should be punished, the 12-member jury comes up deadlocked – a split representing the divided opinions of the Athenian people.

Again it is Athena who resolves this strife. She casts a tie-breaking vote for Orestes’ acquittal.

The play finishes with Athena negotiating with the angry Furies. The Furies will be allowed ritual worship and a home within the boundaries of the city, Athena decides, but they can no longer enforce vengeance. That job belongs to the state, not its citizens.

Athena finds a place for the Furies, even if what they represent is no longer welcome. Today that compromise might be called restorative justice, a process aimed at bringing perpetrators* back into the fold but ensuring they respect the prevailing values of that society.

Stasis

Aeschylus’ “Oresteia” anticipated a real-world challenge Athens would face a century later, after war with Sparta and the restoration of democracy in 403 B.C.

The year before, Sparta had conquered Athens and instituted an oligarchy – literally, the “reign of the thirty” – during which many citizens harmed one another. When the Sparta-supported tyrants were expelled, Athenians swore an oath “not to speak ill to anyone of the things that had happened.”

Bad memories were not erased, of course, but the losers were granted amnesty and the public airing of past grievances was forbidden. For Athens’ leaders, stability depended on integrating formerly warring factions back into the same society. They demanded that residents prize peace over vengeance, and perhaps even over justice.

That’s a bitter pill to swallow. So is Homer’s solution to cyclical violence: One side overpowers the other, then demands the survivors forget the harms they suffered.

These are two different strategies for resolving conflict, but in the ancient Greek language, the same word describes the endings to both the “Eumenides” and the “Odyssey”: stasis.

In English translation this noun is commonly used to mean “standing still” or “balance,” but in ancient texts – not just the “Odyssey” and the “Oresteia” but also in Plato, Thucydides and beyond – the most common meaning of “stasis” is “civil strife.”

The modern United States, like ancient Greece, is defined by stasis. On issue after issue, a stubborn subsistence of equal and opposite factions arises: the pandemic, climate change, the result of the 2020 election.

Greek myth and history teach that societal divisions such as these perpetuate themselves, and will continue, violently, unless something dramatic happens. This, I finally understand after a half-century of studying Greek, is why stasis means both “balance” and “strife.”

It’s a revelation that brings no solace. Homer and Aeschylus have the divine Athena to write their endings for them. No gods are conspiring above to free American society from its painful paralysis.

Joel Christensen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

War in Middle East brings uncertainty and higher energy costs to already weakening US economy

Risks for the US economy grow as the war in the Middle East continues to escalate.

China’s muted response over war in Iran reflects Beijing’s delicate calculus as a concerned onlooker

Beijing has denounced US-Israeli action in Iran, but has not rushed to come to the aid of its regional…

Venezuela’s fragile forests face rising risks as US pushes for oil and critical minerals and illegal

The Orinoco Basin is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also rich in oil, gold…