Jim Thompson is the perfect novelist for our crazed times

The author's novels, famous for their bleakly sociopathic depiction of American culture, testify to the insanity and abusiveness that surround us.

Crime fiction often thrives in periods of social and political tension, when readers long for both justice and stability. So it’s no wonder that as the pandemic took root, crime fiction sales rose.

As I explain in my new book, “Detectives in the Shadows,” many of the protagonists of hard-boiled crime fiction, from Philip Marlowe to Jessica Jones, are models of moral authority, humility and empathy.

Doggedly pursuing justice, they defend those in distress, earning little for their efforts.

In 1945, novelist Raymond Chandler famously defined the hard-boiled hero as “a man … who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid… He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it.”

These were reassuring characters who served as models of competent leadership and ideal authority figures. But it didn’t exactly paint the full American picture. In truth, no matter how many Marlowes or Joneses came to the rescue, signs of America’s deranged underbelly were always lurking just beneath the surface.

One crime author, the singularly harrowing Jim Thompson, gave this unique brand of American craziness center stage.

Unreliable, deceptive and sadistic

Author of more than 20 novels including “The Killer Inside Me,” “Pop. 1280” and “The Grifters,” Thompson created a sinister army of corrupt police, cunning con-artists and psychopathic murderers.

“The Killer Inside Me,” published in 1952, is his best-known novel. Its narrator is Lou Ford, a 29-year-old Texas sheriff who pretends to be a bland and boring rube but ends up committing every murder in the novel.

Unlike classic hard-boiled characters who understate their own misfortunes but have compassion for others, Ford exults when others suffer. He claims spiritual authority and a superior intellect but displays an “aw-shucks” helplessness to seem innocent.

Unreliable as a narrator, he talks in populist clichés – saying things like “haste makes waste” and “every cloud has a silver lining!” – while confiding in the reader that he “should have been a college professor or something like that.” He sometimes references his “sickness,” hinting he is schizophrenic, but he shows no signs of psychosis – only psychopathy.

Most of all, he consistently and calculatingly shirks responsibility, making sure others take the fall for his misdeeds. When a man witnesses him brutalize a town prostitute, he bullies that witness before murdering and framing him.

“Don’t you say I killed her,” he warns the terrified witness. “SHE KILLED HERSELF!”

The gaslit 1950s

The novel arrived at a period in American history that was rife with demagoguery, paranoia and manipulation.

In 1950, the National Security Council paper NSC 68 advised a massive buildup of military power in response to the threat of the Soviet Union. The report remarked that “a democracy can compensate for its natural vulnerability only if it maintains clearly superior overall power in its most inclusive sense,” and warns against our “tendency to expect too much from people widely divergent from us.” It would soon become apparent that retaining power – and a readiness to mistrust those deemed too different – were becoming fundamental to the country’s foreign policy.

Condemning others while behaving badly seemed to be a specialty of the early 1950s. Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade was ruining lives with sensational and unsubstantiated allegations. In 1951, McCarthy accused former Secretary of State Gen. George Marshall of a “conspiracy on a scale so immense as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man,” arguing that his Marshall Plan was helping and appeasing the country’s enemies.

It’s no wonder that American novelist Norman Mailer called the 1950s “years of conformity and depression,” while “Homeward Bound” author Elaine Tyler May described the decade as one of “containment,” with fearful insularity as characteristic of American society as it was of foreign policy.

When Jim Thompson published “The Killer Inside Me,” Lion Books nominated it for the National Book Award, calling it “the most authentically original novel of the year.” An editor at the New American Library found in his books “the passions of men and women revealed in their naked, primeval fury.” Thompson’s characters, from the gloating gaslighter Lou Ford to the messianic delusionist Nick Corey, echoed the paranoid thoughts, delusions and deceptions already patent in 1950s politics.

The writer’s fiction dismantles point-by-point the classical hard-boiled heroes whose word was good and whose ethics were reliable. Its real bleakness comes from the vacuum that replaces any sense of accountability, empathy or reliability.

His novels are chilling precisely because they smash the beloved American illusion that with rugged individualism comes rugged integrity.

Echoes today

“The Killer Inside Me” is a testament to moral accountability exultantly shredded, and its resonance today is uncanny.

America has long embraced the figure of the unhinged or explosive person in entertainment, advertising, sports and politics.

But today’s craziness has reached another level. From Walmart to the White House, Americans are claiming to be both completely righteous and entirely blameless.

Whether it’s the Florida man advancing on fellow Costco shoppers, bellowing “I feel threatened!” the New Jersey woman trying to have innocent neighbors arrested for building a patio on their own property, or the president insisting that he takes no responsibility as over 150,000 Americans die of COVID-19, our current moment is the nightmarish version of society that Thompson envisioned.

As Stephen King famously wrote in the introduction to a 2011 edition of Killer, “In Lou Ford, Jim Thompson drew for the first time a picture of the Great American Sociopath.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

In a sense, the conduct is not new, even if it now readily goes viral on social media. Men have long complained of blamelessness while harming women, and whites of both sexes have simulated fear while attacking people of color. The wealthy have long encouraged the poor to take personal responsibility for privations they themselves caused. Individuals historically most called to account are curiously those who have the least to answer for.

Those in power readily pass the buck, even managing to seem innocent or misguided. The contrived specter of helplessness – combined with claims of absolute conviction – create chaos and dissolve accountability. That Thompson did all this in a book famous for its bleakly sociopathic vision testifies to the insanity and abusiveness that surround us.

A torrent of lies and injustice has demoralized Americans much as it dejected Ford’s victims. To me, we are living in Thompson’s world and can only dream of such fundamentals as honesty, empathy and accountability.

Susanna Lee does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How a largely forgotten Supreme Court case can help prevent an executive branch takeover of federal

An FBI raid on a Georgia elections facility has sparked concern about Trump administration interference…

Do special election results spell doom for Republicans in 2026?

Special election results have anticipated recent midterm outcomes. With Democrats now overperforming,…

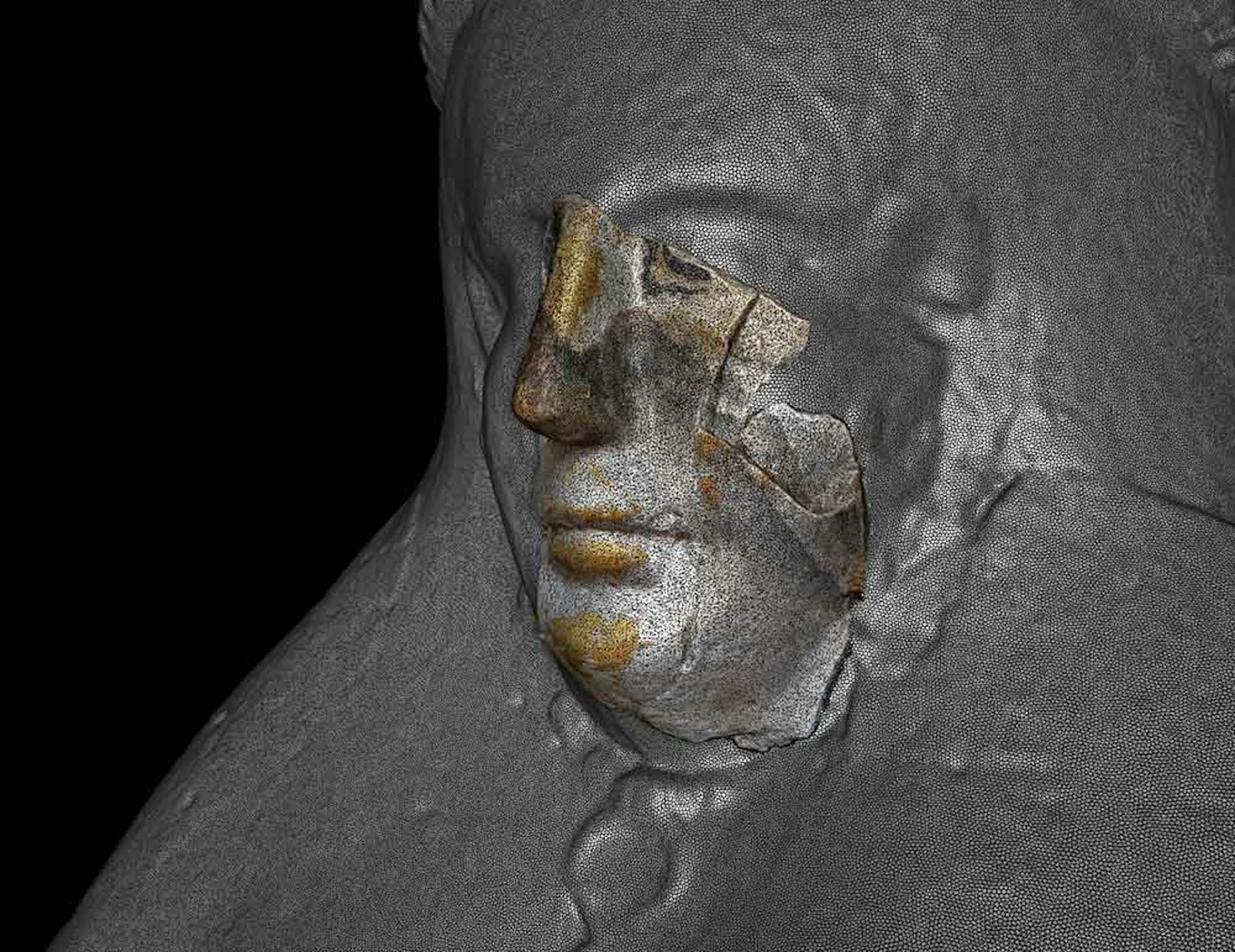

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…