The Beatles' revolutionary use of recording technology in 'Abbey Road'

As the album celebrates its 50th anniversary, an expert in sound recording details how the band deployed stereo and synthesizers to put a unique artistic stamp on their final album.

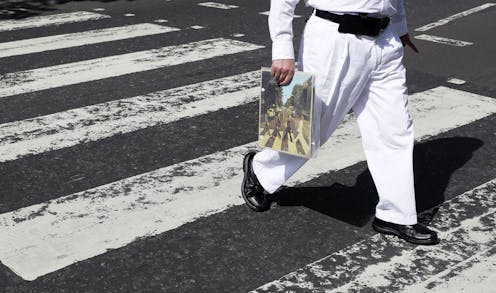

With its cheery singles, theatrical medley and iconic cover, The Beatles’ 11th – and last – studio album, “Abbey Road,” holds a special place in the hearts of the band’s fans.

But as the album celebrates its 50th anniversary, few may realize just how groundbreaking its tracks were for the band.

In my forthcoming book, “Recording Analysis: How the Record Shapes the Song,” I show how the recording process can enhance the artistry of songs, and “Abbey Road” is one of the albums I highlight.

Beginning with 1965’s “Rubber Soul,” The Beatles started exploring new sounds. This quest continued in “Abbey Road,” where the band was able to deftly incorporate emerging recording technology in a way that set the album apart from everything they had previously done.

Sound in motion

“Abbey Road” is the first album that the band released in stereo only.

Stereo was established in the early 1930s as a way to capture and replicate the way humans hear sounds. Stereo recordings contain two separate channels of sound – similar to our two ears – while mono contains everything on one channel.

Stereo’s two channels can create the illusion of sounds emerging from different directions, with some coming from the listener’s left and others coming from the right. In mono, all sounds are always centered.

The Beatles had recorded all their previous albums in mono, with stereo versions made without the Beatles’ participation. In “Abbey Road,” however, stereo is central to the album’s creative vision.

Take the opening minute of “Here Comes the Sun,” the first track on the record’s second side.

If you listen to the record on a stereo, George Harrison’s acoustic guitar emerges from the left speaker. It’s soon joined by several delicate synthesizer sounds. At the end of the song’s introduction, a lone synthesizer sound gradually sweeps from the left speaker to the listener’s center.

Harrison’s voice then enters in the center, in front of the listener, and is joined by strings located toward the right speaker’s location. This sort of sonic movement can only happen in stereo – and The Beatles masterfully deployed this effect.

Then there are Ringo Starr’s drums in “The End,” which fill the entire sonic space, from left to right. But each drum is individually fixed in a separate position, creating the illusion of many drums in multiple locations – a dramatic cacophony of rhythms that’s especially noticeable in the track’s drum solo.

Enter: The synthesizer

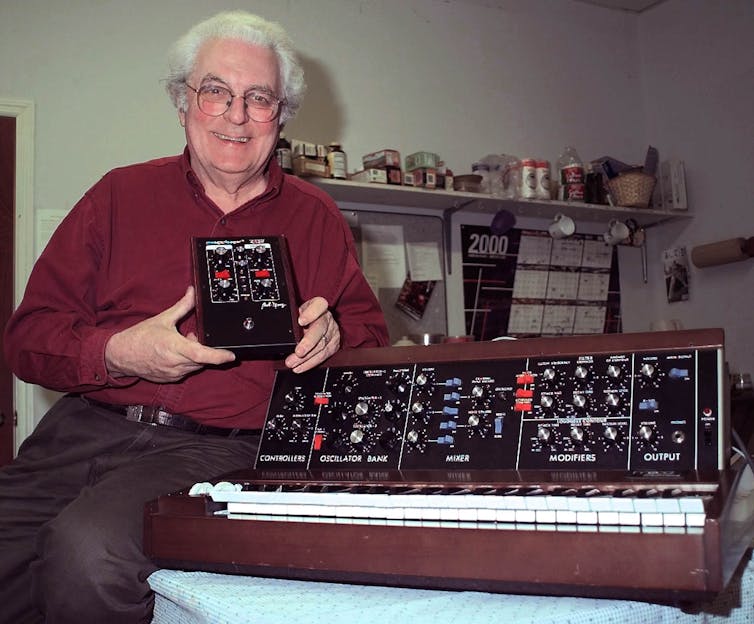

In the mid-1960s, an engineer named Robert Moog invented the modular synthesizer, a new type of instrument that generated unique sounds from oscillators and electronic controls that could be used to play melodies or enhance tracks with sound effects.

Harrison received a demonstration of the device in October 1968. A month later, he ordered one of his own.

The Beatles are among the very first popular musicians to use this revolutionary instrument. Harrison first played it during the “Abbey Road” sessions in August 1969, when he used it for the track “Because.”

The synthesizer ended up being used in three other tracks on the album: “Here Comes the Sun,” “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “I Want You (She’s So Heavy).”

The Beatles didn’t incorporate the synthesizer for novelty or effect, as the Ran-Dells did in their 1963 hit “Martian Hop” and The Monkees did in their 1967 song “Star Collector.”

Instead, on “Abbey Road,” the band capitalizes on the synthesizer’s versatility, creatively using it to enhance, rather than dominate, their tracks.

In some cases, the synthesizer simply sounds like another instrument: In “Here Comes the Sun,” the Moog mimics the guitar. In other tracks, like “Because,” the synthesizer actually carries the song’s main melody, effectively replacing the band’s voices.

A dramatic pause

In 1969, the LP record still reigned supreme. The Walkman – the device that made music a more private and portable experience – wouldn’t be invented for another 10 years.

So when “Abbey Road” was released, people still listened to music in a room, either alone or with friends, on a record player.

The record had two sides; after the last song on the first side, you had to get up, flip the LP and drop the needle – a process that could take about a minute.

The Beatles, conscious of this process, incorporated this pause into the album’s overall experience.

“I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” ends side one. It’s full of energetic sounds that span the entire left-to-right spectrum of stereo, bounce from lower to higher frequencies and include sweeps of white noise synthesizer sounds. These sounds gradually amass throughout the course of the song, the tension growing – until it suddenly stops: the point at which John Lennon decided the tape should be cut.

The silence in the gap of time it takes to flip the LP allows the dramatic and sudden conclusion of side one to reverberate within the listener.

Then side two begins, and not with a bang: It’s the gentle, thin guitar of “Here Comes the Sun.” The transition represents the greatest contrast between any two tracks on the album.

That gap of silence between each side is integral to the album, an experience you can’t have listening to “Abbey Road” on Spotify.

“Abbey Road,” perhaps more than any other Beatles album, shows how a song can be poetically written and an instrument deftly played. But the way a track is recorded can be the artist’s final stamp on the song.

William D. Moylan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…

While the US government is investigating unidentified anomalous phenomena, academic researchers stud

Surveys have found that researchers studying UAPs can face pushback from mentors and colleagues, even…