Is it even possible to connect '13 Reasons Why' to teen suicide?

Over the past decade, more teens are attempting suicide. The trend has vexed researchers, but it that much more difficult to determine whether a fictional TV show has had any role.

Netflix recently released the third season of “13 Reasons Why,” and the Salt Lake City school district has already sent home a letter to parents imploring them to discourage their children from watching the show.

In season one, which was released in 2017, the protagonist died by suicide. Since then, studies have emerged about the effects of the show, and media has tended to cover the findings with alarmist headlines. In response to public anxiety, Netflix edited out the original suicide scene this past July.

Many parents across the country fear that, in watching the show, kids might be inspired, consciously or subconsciously, to mimic the characters – what’s called a “copycat effect.”

Is their concern founded?

We know more teens have been dying by suicide over the past decade. But as suicide researchers, we also know how difficult it is to investigate the causes.

Determining whether a fictional TV show has any effect on suicide is that much more challenging, and many of the studies that have come out on “13 Reasons Why” leave room for interpretation.

Practical and ethical constraints

In 2017, approximately 47,000 Americans died by suicide, making it the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S.

But to study trends in suicide deaths, researchers must rely on large-scale, population-based data, such as Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System. There’s no additional information on media consumption – and certainly no opportunity to ask questions like, “Did you watch ‘13 Reasons Why?’”

In reality, it’s impossible to conduct truly causal research on media consumption and suicide. For practical and ethical reasons, you couldn’t show one group of depressed teens “13 Reasons Why,” forbid another group from watching it and then see how many teens from each group died by suicide over an ensuing period of time.

In lieu of these limitations, some researchers have studied indicators of suicidal thoughts or behavior.

A 2018 study of suicide-related admissions in a Canadian pediatric hospital found a higher-than-expected admission rate following the release of “13 Reasons Why.” But this increase cannot be definitely linked to the show; we don’t know if these children watched it. Also, not all suicide attempts result in hospitalization, so these results might not capture the full scope of the show’s connection to self-harming behavior.

Another study examined Crisis Text Line usage after the show’s premiere and found that usage briefly spiked for the two days after the show’s premiere – but declined to a below-average call volume for the next month and a half.

Talking to viewers

Then there are researchers who have interviewed people who had already watched the show.

In one study, researchers spoke with 87 youth with psychiatric conditions; 49% of them reported that they’d seen “13 Reasons Why.” About half of those who watched the show felt that it made them more suicidal.

A larger study of 21,062 Brazilian adolescents explored the relationship between watching “13 Reasons Why” and suicidal thoughts. However, most participants with histories of suicidal thoughts – particularly those who weren’t currently in a depressive episode – actually reported decreases in suicidal thoughts after viewing the show.

And a 2019 study of 818 college students found that those who watched the show understood suicide better but scored no higher on measures of suicide risk than those who did not watch it. However, the study took place several months after participants viewed the show, so the results weren’t able to identify any short-term risk increase.

A spike in deaths?

Another approach involves tracking the number of teen suicide deaths before and after an event.

That’s what epidemiologist Jeff Bridge and some of his colleagues did. In a study released earlier this year in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, they found that there was a statistically significant spike in suicide deaths among boys ages 10 to 17 in the month following the show’s first season, which was released in March 2017. There was also a slight increase in suicide deaths among girls ages 10 to 17 as well, but it wasn’t large enough to be statistically significant.

The significant spike among boys – but not girls – was surprising. The character who dies by suicide in the show is a teenage girl, and studies have shown that the more similarities someone shares with a person who has committed suicide, the stronger the copycat effect.

But there could be an explanation for this. Across all age groups, men are more than three times as likely as women to die by suicide. Bridge’s study only looked at deaths, not attempts. So it’s possible the spike could be attributed to the fact that males are much more likely to die from a suicide attempt.

Nonetheless, as with the hospital admission study, the spike can’t be linked to the show with certainty. We don’t know whether these people watched the show.

Despite these unknowns, the spike in suicide deaths that Bridge was able to identify was alarming. This, combined with the fact that the show did not follow well-established media guidelines for addressing suicide, led to considerable public backlash.

Where the real danger lies

Yet all of the attention being paid to a fictional television show could be misplaced.

Sociologist Stephen Stack has sifted through decades of research on the relationship between the media and suicide. He was able to show that stories about real people had a greater effect than those about fictional characters. And articles about suicide in the newspaper had an 82% greater effect on suicide rates than television news coverage of suicides.

So the fact that “13 Reasons Why” is a fictional television drama could mean that the concern is overblown. It’s getting all of the attention; meanwhile, real suicides are still being irresponsibly covered by the media.

Nonetheless, suicide is such a serious issue that Netflix is correct to proceed with caution.

Michael R. Nadorff receives funding from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association and the National Institute of Mental Health.

Emily Lund does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Supreme Court rules against Trump’s emergency tariffs – but leaves key questions unanswered

The ruling strikes down most of the Trump administration’s current tariffs, with more limited options…

Enforcing Prohibition with a massive new federal force of poorly trained agents didn’t go so well in

Both Prohibition and current mass deportation efforts were hastily built, staffed by people permitted…

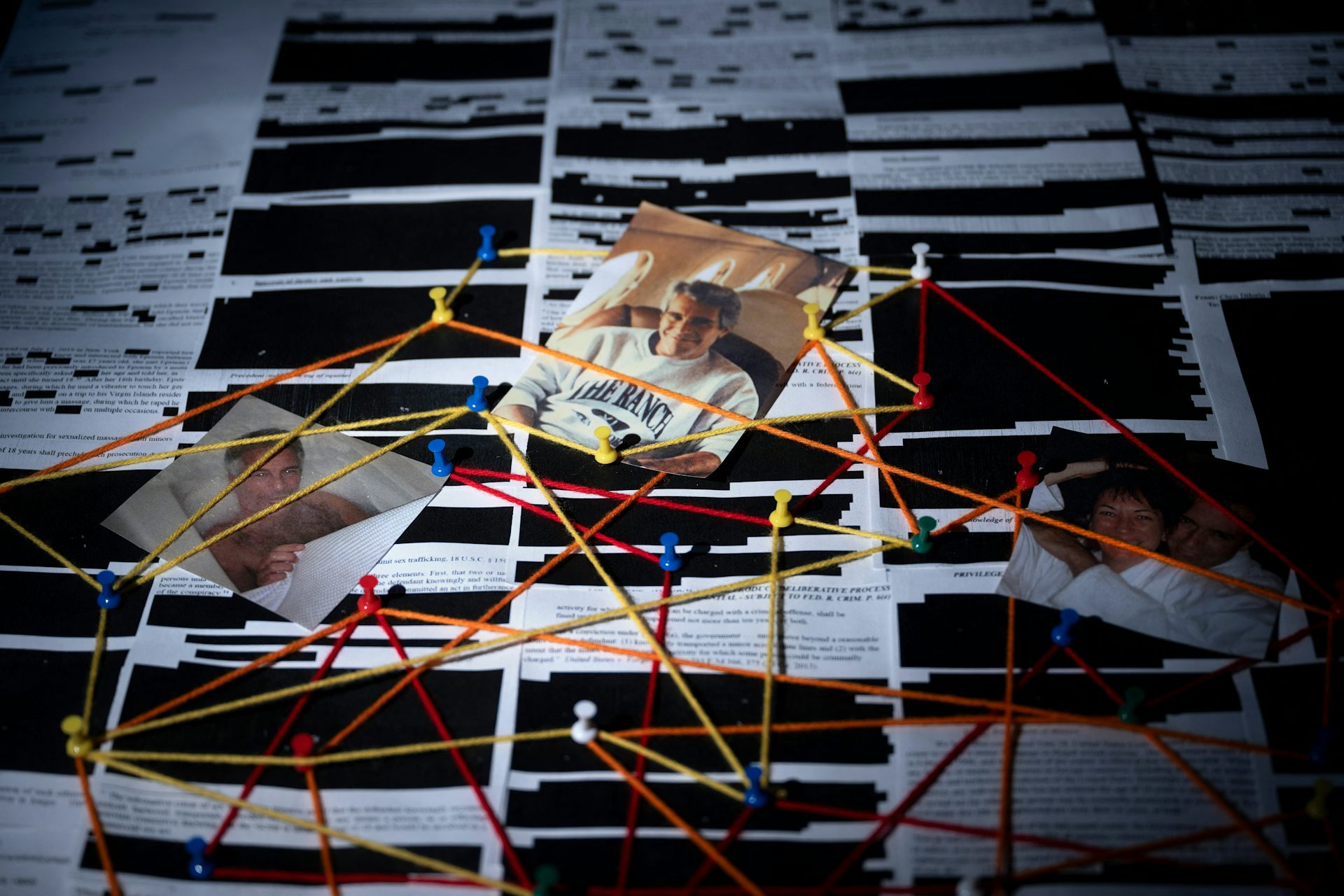

Individual donors provide only a small slice of university research funding – but Jeffrey Epstein’s

A small portion of university research funding comes from individual donors. Most universities have…